Abstract

Anlotinib is effective in treatment of many kinds of malignant cancer, but its antineoplastic effects on esophageal cancer remains unclear. This study aims to investigate its impact on esophageal cancer and the underlying mechanisms. Anlotiniband 5-fluorouracil + cisplatin (5-FU + DDP) was administered separately to human esophageal cancer TE- 1 cells tumor xenograft mouse models every 3 days. Tumor size and body weight were measured before each treatment and at the end of the experiment. In vitro studies were conducted using TE- 1 cells to examine the effects of Anlotinib. Cell viability, migration, proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle, their regulatory proteins and the transcriptomic changes were analyzed. Anlotinib reduced tumor size, tumor weight, and the ratio of tumor weight to body weight in vivo. It decreased the viability of TE- 1 cells, with a 50% growth-inhibitory concentration of 9.454 μM for 24 h, induced apoptosis, and arrested TE- 1 cell cycle in the S phase. It inhibited migration and proliferation while negatively regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Enhanced expressions of P21, Bax, and lowered expressions of cyclin A1, cyclin B1, CDK1, PI3K, Akt, p-Akt, and Bcl-2 were observed after Anlotinib treatment. Anlotinib exhibits antineoplastic activity against human esophageal cancer TE- 1 cells by negatively regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, consequently altering the expressions of proteins related to proliferation, apoptosis, and the cell cycle.

1 Introduction

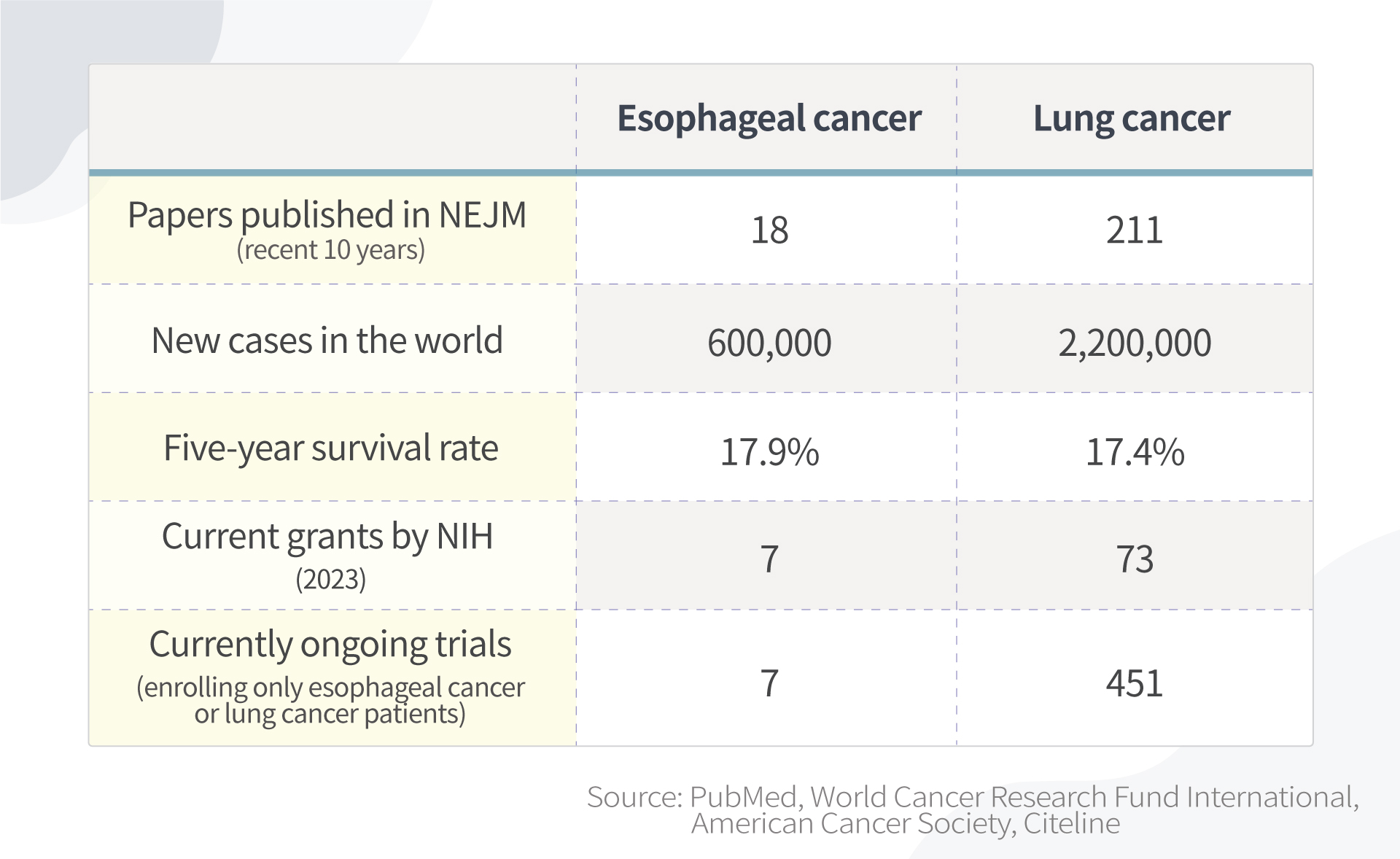

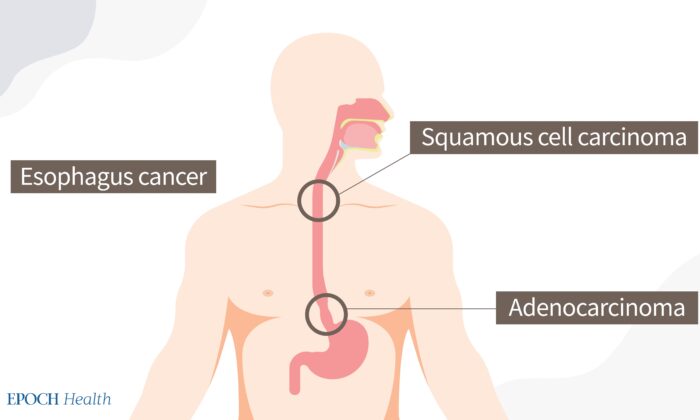

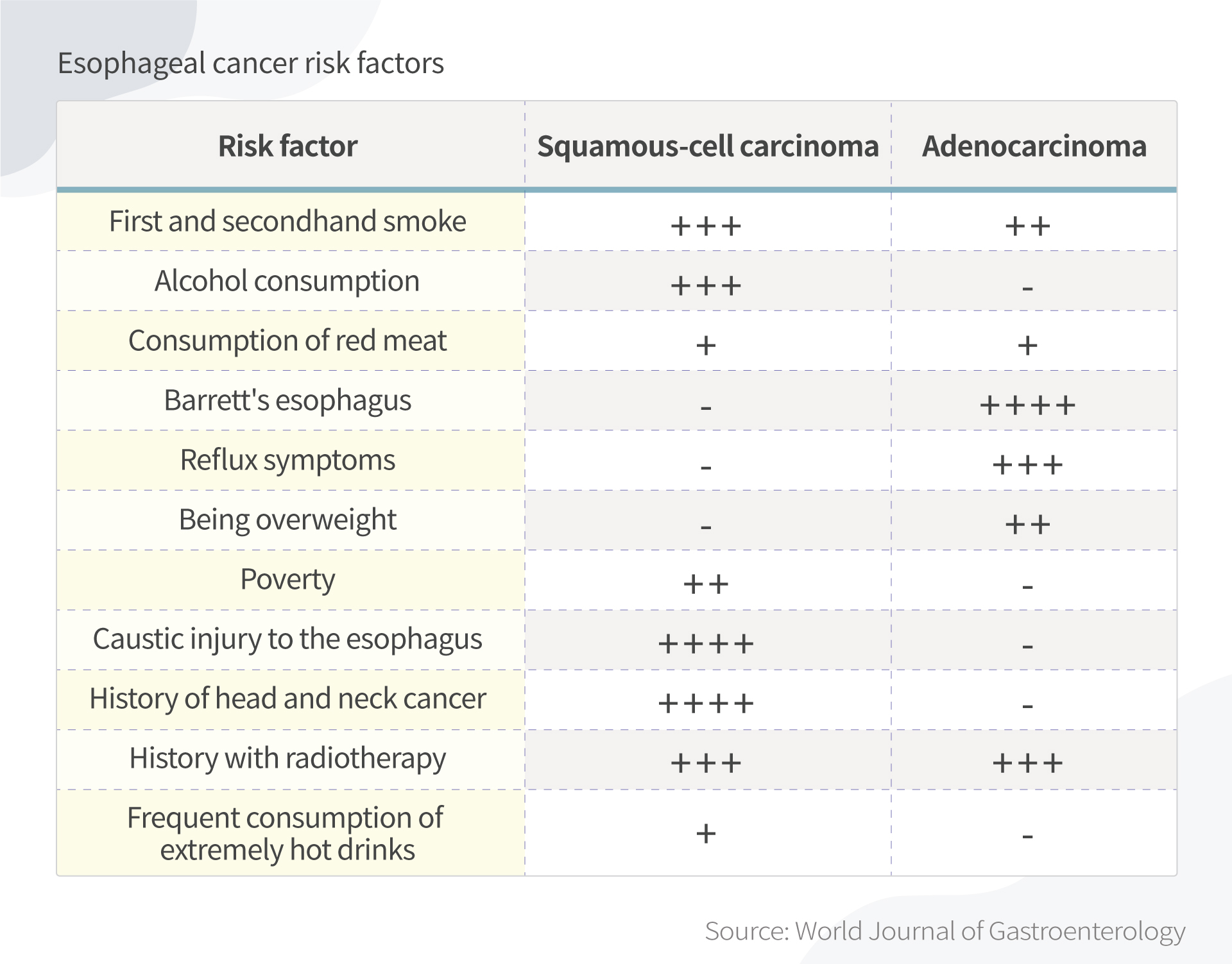

Esophageal cancer (EC) is characterized by high morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. It consists of two major histologic subtypes: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma(SCC), with SCC being the predominant subtype. EC exhibits significant regional variations globally. Certain regions in Asia, East Africa, and South America, such as China, Iran, Kenya, and Brazil, have higher incidence rates of esophageal cancer. This is associated with local factors such as diet, lifestyle, cooking methods, food choices, and environmental factors. Despite significant advancements in surgery, preoperative chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the survival rate remains low, with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 15 to 20%, and a median survival time of 1.5 years [3]. This is despite the considerable progress in surgery, preoperative chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. The therapy regimen primarily depends on the physical condition and tumor stage, typically classified by the TMN stage of EC patients. Chemotherapy is widely applied to patients who are not suitable for surgery.

Anlotinib is a recently approved chemotherapeutic agent that has gained approval for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer as a third-line therapy option in China [4, 5]. It functions as a multikinase inhibitor, targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (EGFR) 1–3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1–4, the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and the stem cell factor receptor to inhibit neoangiogenesis and tumor progression [6,7,8]. Anlotinib also inhibits the activity of basic fibroblast growth factor receptor (bFGFR). bFGFR is another crucial receptor associated with tumor growth and angiogenesis. By affecting the bFGFR signaling pathway, Anlotinib can regulate cell growth, differentiation, and migration, thereby influencing the development of tumors. Anlotinib has been found to induce apoptosis in tumor cells, which refers to programmed cell death. This is an essential part of the normal cell lifecycle but is often disrupted in tumors. By prompting tumor cells to undergo programmed cell death, Anlotinib helps inhibit the growth of tumors.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated the efficacy of anlotinib against intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [9], soft tissue sarcoma [10], thyroid cancer [11], and colorectal cancer [12]. It exhibited notable therapeutic effects against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) on patient-derived xenograft models when combined with chemoradiotherapy, while the exact mechanism remains unclear. Therefore, our study was designed to investigate the efficacy and underlying mechanism of anlotinibon ESCC using tumor xenograft animal models and TE- 1 cells.

Discussion

In China, approximately 240,000 new cases of EC are diagnosed each year, with EC ranking as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality [13,14,15]. Many patients receive diagnoses at advanced stages, leading to 5-year survival rate of merely 5%. The discovery of new medicines for treating EC is an imperative need. Current studies on anlotinib have mostly focused on its anticancer activity against advanced non-small-cell lung cancer [7]. Jingzhen Shi combined anlotinib with chemoradiotherapy to treat EC with good achievements [16]. These results have inspired us to investigate the underlying mechanisms behind anlotinib’s effects on EC.

In our study, anlotinib demonstrated excellent antineoplastic activity against EC in vivo, with less body weight loss in comparison to the 5-FU + DDP treatment. This effect was corroborated by the outcomes observed in the TE-1 cell line, where anlotinib exhibited an IC50 value of 9.454 μM. Furthermore, anlotinib induced TE- 1 cell apoptosis and notably arrested the cell cycle in the S phase, thereby inhibiting migration and proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. These findings indicate that Anlotinib has potential therapeutic capabilities against esophageal cancer, exhibiting significant anti-tumor effects both in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, Anlotinib effectively inhibits the migration and proliferation of esophageal cancer cells by inducing apoptosis and arresting the cell cycle, providing important evidence for its further research and clinical application as an anti-cancer treatment.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is a crucial cellular signaling cascade involved in regulating various biological processes such as cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism [17, 18]. Its name derives from two key proteins involved in the pathway: phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (Akt), also known as protein kinase B activated kinase (PKB). PI3K is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) on the cell membrane [19, 20]. Upon activation, PIP3 can bind and activate Akt, thereby initiating downstream signaling cascades. Akt, a critical regulatory protein in the PI3K/Akt pathway, promotes cell survival and proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis. Akt exerts its effects by phosphorylating various cellular factors, cell cycle proteins, and transcription factors, thereby modulating cellular physiology. Aberrant activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is closely associated with the onset and progression of various diseases, including cancer [21, 22]. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the proliferation, survival, and invasion of tumor cells [23, 24] including TE- 1 cells [25,26,27]. The activation of PI3K promotes Akt to be phosphorylated intop-Akt, p-Akt acts on its downstream proteins to enhance TE-1 cell survival, proliferation and invasion. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway can also participate in cell survival and inflammatory responses by activating NF-κB (nuclear factor-kappa B). NF-κB is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of various genes, including those associated with cell survival, proliferation, and immune responses. The excessive activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is closely associated with the occurrence and development of various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and neurological disorders. Therefore, this signaling pathway has become a crucial target for drug development, and drugs targeting its abnormal activation are being investigated for the treatment of diseases such as cancer. Our findings indicated that anlotinib treatment notably downregulated PI3K, Akt, and p-Akt, aligning with the results of other studies [9, 10].

Survivin plays a significant role in regulating cell division, apoptosis (programmed cell death), and cell survival. It is a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of proteins, which are characterized by their ability to inhibit apoptosis and promote cell survival [28, 29]. Survivin is overexpressed in various types of human tumor cells, including lung cancer, breast cancers, EC, as well as TE-1 cells, as indicated by our research. The suppression of survivin promotes tumor cells apoptosis and enhances radiosensitivity of esophageal cancer cells [30,31,32]. Besides, Bax serves as an apoptosis promoter, while Bcl-2, an important homolog of Bax, plays the inverse effects of Bax [33, 34]. Our results demonstrated that anlotinib treatment significantly promoted TE- 1 cells apoptosis through suppression of survivin, Bcl-2 and enhancement of Bax expressions. By understanding how Anlotinib regulates key genes such as survivin, Bcl-2, and Bax to promote apoptosis in TE-1 cells, we can gain deeper insights into its mechanism of action in anticancer processes, which can guide further clinical research and the development of more effective treatment strategies.

Cyclin A1 is the product of CCNA1 gene expression. Except Akt as one of the two central proteins affectd by anlotinib treatment, Cyclin A1 was the other central protein which interacting with other proteins to regulate cell cycle. Cyclin A1 which working together with cyclinB1 to promote S to G2/M phase transition. The combination of cyclin A1 or cyclinB1 to CDK1 triggers cell cycle into mitosis [35,36,37]. P21 is currently recognized as a potent universal CDK inhibitor which forms complexes with CDKs and cyclins to arrest cell cycle [38, 39]. Anlotinib negatively regulated cyclin A1, cyclin B1 and CDK1 expressions while positively up regulated P21 expression in TE- 1 cells. These observations elucidate the mechanism underlying its effects on cell cycle arrest.

This article has some shortcomings. Firstly, although the study elucidated the negative regulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway by Anlotinib, the underlying mechanisms of this regulation have not been fully explored. Further mechanistic studies are needed to analyze the molecular pathways involved and confirm the observed effects. Secondly, TE-1 cells may not fully represent the heterogeneity of esophageal cancer. Including other esophageal cancer cell lines or samples originating from patients could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of Anlotinib in different molecular subtypes of the disease.

5 Conclusions

Anlotinib can induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, inhibit migration and proliferation of TE- 1 cells by negatively regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, and consequently regulating expressions of apoptosis- related and cell-cycle-related proteins. The detailed underlying mechanism may be further elucidated in future research.