SLAUGHTERHOUSE BIG FIVE:

EVERYTHING WAS UGLY AND NOTHING WORKED

It was just before closing time at a Verizon store in Bushwick, New York last May when I burst through the door, sweaty and exasperated. I had just sprinted—okay I walked, but briskly—from another Verizon outlet a few blocks away in the hopes I’d make it before they closed shop for the night. I was looking for a SIM card that would fit a refurbished 2012 Samsung Galaxy S3 that I had recently purchased on eBay, but the previous three Verizon stores I visited didn’t have any chips that would fit such an old model.

When I explained my predicament to the salesperson, he laughed in my face.

“You want to switch from you current phone to an… S3?” he asked incredulously.

I explained my situation. I was about to embark on a month without intentionally using any services or products produced by the so-called “Big Five” tech companies: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. At that point I had found adequate, open source replacements for most of the services offered by these companies, but ditching the Android OS, which is developed by Google, was proving difficult.

Most of the tech I use on a day-to-day basis is pretty utilitarian. At the time I was using a cheap ASUS laptop at work and a homebrew PC at my apartment. My phone was a Verizon-specific version of the Samsung Galaxy J3, a 2016 model that cost a little over $100 new. They weren’t fancy, but they’ve reliably met most of my needs for years.

For the past week and a half I had spent most of my evenings trying to port an independent mobile OS called Sailfish onto my phone without any luck. As it turned out, Verizon had locked the bootloader on my phone model, which is so obscure that no one in the vibrant Android hacking community had dedicated much time to figuring out a workaround. If I wanted to use Sailfish, I was going to have to get a different phone.

I remembered using a Galaxy S3 while living in India a few years ago and liking it well enough. I ultimately decided to go with that model after finding extensive documentation online from others who had had success porting unofficial operating systems onto their phones. So two days and $20-plus-shipping later, I was in possession of a surprisingly new-looking Verizon Galaxy S3. The only thing that remained to do before loading Sailfish onto the device was to find a SIM card that fit. SIM cards come in three different sizes—standard, micro, and nano—and my nano SIM wouldn’t fit in the S3’s micro SIM port.

By the time I explained all this to the Verizon employee, he had found a SIM card that would work. As he navigated the Android setup menu he asked me if I wanted him to link my Google account to the phone. “Oh that’s right,” he said, looking up from the phone and laughing. “Sorry, it’s just a habit.”

I could hardly blame him for the slipup. I’m probably the only person who has ever come into the store who didn’t want to synchronize the Google services they use with their phone. It’d be senseless to resist that kind of convenience and Google knows this, which is why Android prompts you to enter your Google credentials before you’ve even reached the phone’s dashboard for the first time. But what I wanted to know is whether there was another way.

Want a more in-depth explanation of why you might want to quit the Big Five? Check out my introductory blog post on how this experiment came about

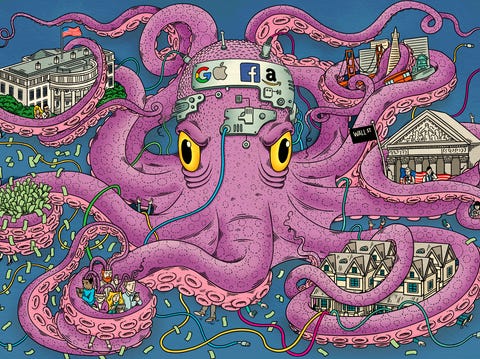

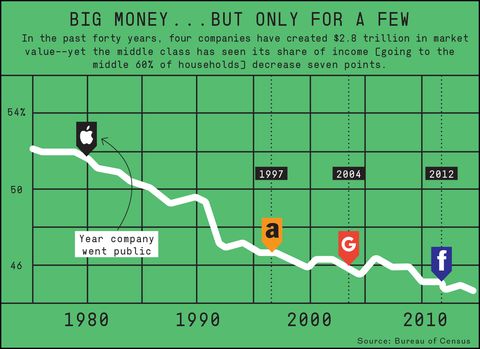

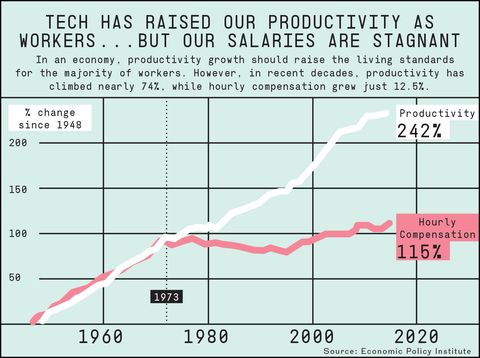

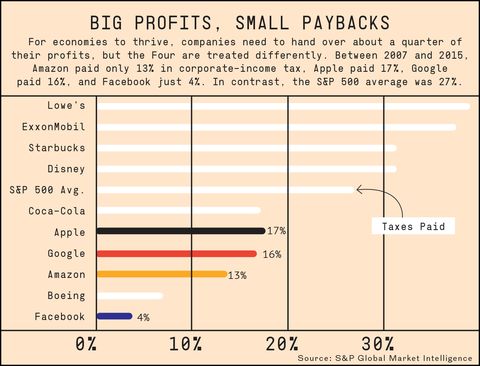

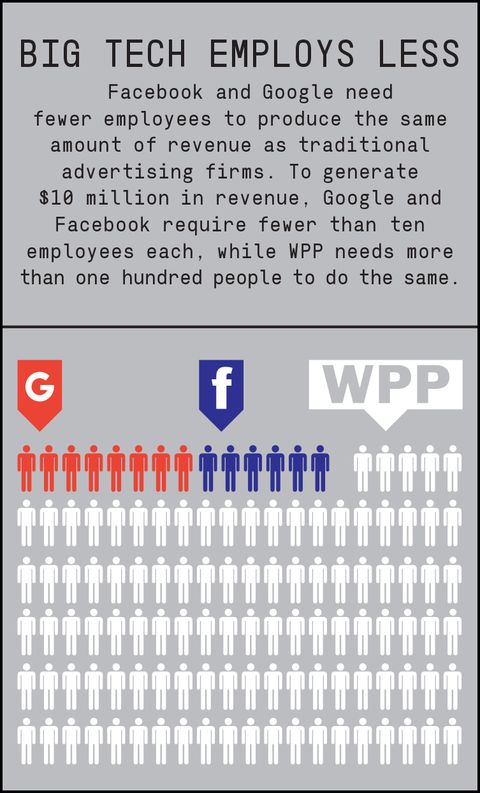

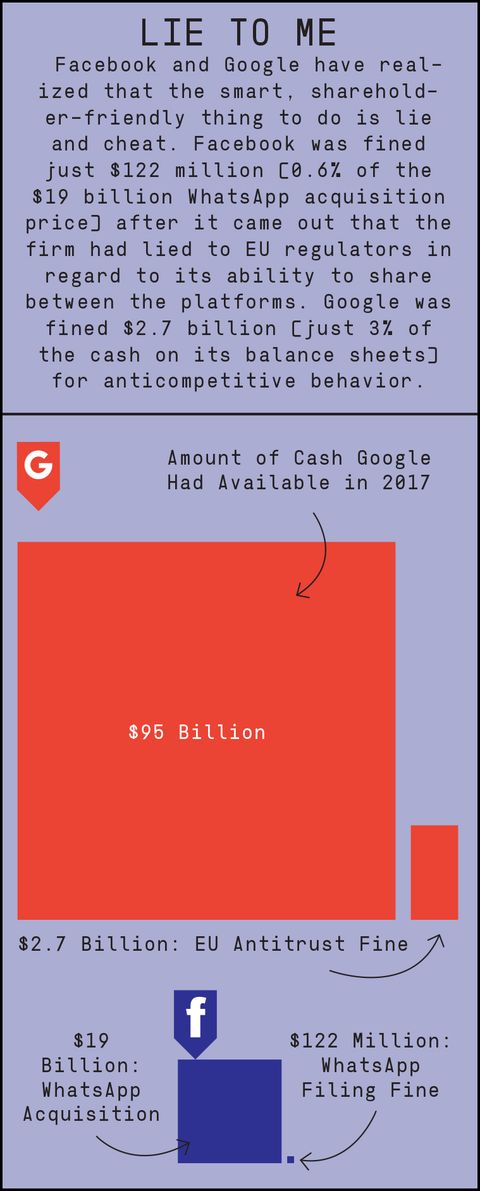

By now, it’s common knowledge that Google, Facebook, and Amazon are harvesting as much of our personal data as they can get their hands on to feed us targeted ads, train artificial intelligence, and sell us things before we know we need them. The results of this ruthless data-driven hypercapitalism speak for themselves: Today, the Big Five tech companies are worth a combined total of $3 trillion dollars. When I started my month without the Big Five in May, Google’s parent company Alphabet, Amazon, and Apple were racing to be the first company in history with stock worth $1 trillion. In August, Apple became the first to reach this milestone and just a few weeks later Amazon’s market cap also briefly passed $1 trillion.

With the exception of Microsoft and Apple, these fortunes were not built by selling wildly popular products, but by collecting massive amounts of user data in order to more effectively sell us stuff. At the same time, this data has also been abused to swing elections and abet state surveillance. For most of us, giving away our data was seen as the price of convenience—Google and Facebook are “free” to use, after all.

Although Amazon now sells its own products, its rapid growth was fueled by selling other people’s products. This gave the company unprecedented access to consumer habits and data, which it used to spin out its own consumer goods brands and gain invaluable experience in logistics and web hosting. Both its in-house consumer brands and Amazon Web Services are now core parts of Amazon.

The widespread adoption of Microsoft and Apple products over the past 40 years, meanwhile, was no accident, but the result of monopoly-focused business tactics. The end result was that their products appear to be a natural default. You’re either a Mac person or a Windows person and you stick to your brand because that’s the way it’s always been.

As the open internet was swallowed whole by the megacorporations of Silicon Valley, however, a revolution was occurring in free, open source software (FOSS). Although FOSS can trace its roots back to the crew working at MIT’s artificial intelligence laboratory in the early 1980s, it broke into the mainstream in a big way largely due to the creation of Linux, an open operating system developed in the early 90s. These days there’s a galaxy of free and open source software that offers adequate alternatives to most Big Five services, and much of it is powered by Linux. In fact, a lot of the Big Five services you use on a daily basis are probably also based on Linux or open source software that has had some proprietary code grafted on top of it before it was repackaged and sold back to you.

My goal with going a month without the Big Five was to see if I could rely solely on open source or independent software without compromising what I was able to accomplish with proprietary code. Basically, could I live my normal life with open source alternatives?

Going into the experiment, I realized that there was a good chance I’d come crawling back to some of the Big Five services when it was over. Yet as I discovered over the four weeks, switching to independent alternatives didn’t negatively affect most parts of my life, but it did take a little getting used to.

Before diving into the nitty gritty of what worked and what didn’t, however, let me explain the limits of the experiment.

LIMITATIONS

After announcing my intention to relinquish Big Five services for a month, People On The Internet pointed out that my experiment would fail because I would almost certainly visit a website hosted by Amazon’s cloud service at some point, thereby indirectly putting money into Jeff Bezos’s pocket. This is, of course, true. Amazon Web Services hosts a number of popular sites that I use on a regular basis, such as Netflix, Reddit, Spotify, SoundCloud, and Yelp, all of which I visited at least once during the month.

Unfortunately, avoiding this kind of indirect support of Big Five through their back-end services will become even more difficult to avoid in the future. For example, Google is beginning to lay its own undersea internet cables, creating the infrastructure for totally networked homes, and developing self-driving car services. Microsoft is aggressively pursuing cloud computing platforms and recently acquired GitHub, a code repository I frequently use while teaching myself how to program. Amazon moved into the space data business and is also working on networking your home with devices like Alexa, and Facebook still controls how much of the world communicates through its website, Instagram, and WhatsApp.

Yet even if I did scrupulously avoid visiting sites hosted on Amazon Web Services, the experiment was designed to be temporary. This meant that rather than shutting down my work Gmail accounts, I had them forward my email to an alternative email provider that I would then use to send and receive emails. There were also inevitably important files that I neglected to transfer from my Google Drive to an alternative hosting service when I was preparing for the experiment, so I had to log in to my Google account to retrieve those files and move them over. Or there were times when I was attempting to change a YouTube link to a HookTube link and accidentally landed on YouTube.

I don’t think the handful of lapses alluded to above undercut the spirit of the experiment, however, since I wasn’t intentionally using any services offered by the Big Five. If I were permanently planning to leave the Big Five I would have transferred all my files from Google Drive, deleted my Gmail accounts, and so on.

So with these experimental limitations in mind, I present the Motherboard Guide to Quitting the Big Five, based on my own experience in May 2018.

THE MOTHERBOARD GUIDE

TO QUITTING THE BIG FIVE

Image: Motherboard

HOW TO QUIT FACEBOOK

My experiment in leaving the Big Five arguably began back in March, when I deleted my Facebook account in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Of all the companies I abandoned for this experiment, Facebook and its subsidiaries were by far the easiest. I have tried and failed to start an Instagram account several times over the years. I find Instagram unbelievably boring and I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ll never understand its already large, and still growing, appeal.

Quitting WhatsApp was more difficult since I used it to keep in touch with my friends abroad, many of whom live in countries where WhatsApp is the default communication tool. With friends and family in the US, I switched over to the encrypted chat app Telegram or just stuck to normal SMS and email. As I soon learned, the ideal messaging platform doesn’t exist. If security is your thing, WhatsApp, Messenger, Signal, and Telegram all have their flaws and all offer comparable services. The main advantage of WhatsApp is that nearly a quarter of the world already uses it.

I have been off Facebook for a few months now and my only regret is that I didn’t leave sooner. Although there is admittedly something of a phantom-limb effect right after leaving—pulling out my phone in response to imaginary pings from Messenger or reflexively navigating to the Facebook login page only to realize I no longer had a profile—the feeling that I was always missing something quickly subsided. I go out with friends and attend events just as much as I did before. I have no qualms about missing events that I would’ve received a mass Facebook invite to because now I live in blissful ignorance of their occurrence. Contrary to my expectations, my FOMO is at its lowest point in years.

“Contrary to my expectations, my FOMO is at its lowest point in years”

Admittedly, leaving Facebook is a privilege. In many places, Facebook and Messenger are people’s only links to the outside world, or people may depend on Facebook to run their business. It can also make it challenging for people to contact you if you leave. Although I made a point of collecting contact information from my friends before I deleted my account, there were inevitably some I forgot.

During my month without the Big Five, I received an email from an Argentinian friend I hadn’t seen in years who was passing through New York. When we met for dinner, he mentioned how hard I had been to track down without Facebook. Fortunately, I’ve listed my email publicly on my website and still had a Twitter profile at that point, so he was able to find an alternative method of contacting me. But for people who don’t work in industries where it’s normal to make your email public or to have a personal website, these types of missed connections are bound to happen.

As for the actual process of deleting your Facebook profile, it’s pretty simple. I’ve covered the process in detail in another article, but there are a few points you’ll want to consider before taking the plunge. If you’re the type of person who signs up for other apps such as Tinder or Airbnb with your Facebook account, then deleting your Facebook profile is going to be way more of a pain in the ass because you’re going to have to switch all those accounts over to an email login first. Second, if you have hundreds of photo albums dating back to 2008 that you want to save, be prepared to spend a few hours scraping them off of Facebook. (There are scripts that help with this, but I didn’t find any of them to be that efficient.) Other than that, there’s a button on Facebook that will allow you to download all your data in one fell swoop. It includes every like, comment, and event invite from the past decade so you can cherish these internet minutiae until you grow old and die.

Read More: Delete All Your Apps

There are a number of legitimate reasons you might want to consider leaving Facebook. In my case, I left due to my discomfort with the idea that I was giving away huge amounts of intensely personal data to a company that had a history of mishandling its users’ information. I was also getting tired of wasting so much time endlessly scrolling through status updates from people whom I hadn’t seen or talked to for years. I had managed to convince myself that clicking “like” on digital simulacra of people’s lives was socializing and, to borrow Mark Zuckerberg’s favorite word, being part of a “community.”

There’s no doubt that humans are social creatures and that human interaction is a critical part of an individual’s wellbeing. How strange, then, that a mounting body of evidence shows that reducing social media use actually decreases loneliness and feelings of unhappiness. To make matters worse, sometimes Facebook makes us unhappy on purpose.

But even if you have more free time than you know what to do with and don’t mind forking over your data to a multi-billion dollar company that just “runs ads,” you might consider ditching Facebook because it is a breeding ground for disinformation. In the past three years, evidence has emerged that Facebook was a primary vector for sowing political discord in the United States and, so far, Zuckerberg hasn’t demonstrated that his company has the faintest idea of how to stop it. Maybe one day it will figure out an effective filter for fake news, but until then, there’s a good chance that meme your racist uncle just posted was generated by a Russian bot.

Read More: The Impossible Job: Inside Facebook’s Struggle to Moderate 2 Billion People

During Zuckerberg’s testimony before the US Congress in April, Senator Lindsey Graham asked him point blank whether Facebook was a monopoly. Zuckerberg danced around the question and was ultimately unable to provide an example of alternative services offering a similar product to Facebook.

Although there are lots of alternative social media platforms out there, none of them are used by half the world’s population, which is exactly what makes Facebook so valuable. Still, if you want to keep social media in your life, you might want to use an alternative platform, such as Mastodon (a decentralized Twitter imitator) or Ello (a privacy-oriented, ad-free Facebook alternative). You won’t find anyone you know on there, probably, but at least your social media fix won’t come at the cost of your privacy.

HOW TO QUIT APPLE

I’ve only owned two Apple products in my life. One was an old 120 gigabyte iPod classic that I still miss dearly. The other was an iPhone 4 that I got in 2010 and had for a year and a half before I switched to Android and never looked back.

Since I didn’t have any Apple products to relinquish for my monthlong experiment, I used the time for a little introspection on why I dislike Apple products. The main reason is that I was raised using Windows, so I was disincentivized to learn the quirks of a new OS. As I grew older, however, I also found Apple’s “walled-garden” approach to its device ecosystem infuriating. (For many people, however, this closed ecosystem and interoperability between Apple devices is exactly what makes its products attractive.)

Apple’s obsession with total control is perhaps best exemplified by the release of iPhone 7 in 2016, which got rid of the ubiquitous headphone jack that has been used by literally every other digital device since forever and replaced it with a proprietary dongle. This was an affront to Apple’s devout followers, sure, but that didn’t stop the company from selling more than 200 million iPhones last year at around $600 a pop. And yet here we are, years after Apple adopted the dongle, and people are still mourning the loss of the headphone jack.

I know why I don’t use Apple, but even after a month of thinking about it, I still couldn’t rationalize why anyone would spend a night sleeping outside an Apple store to get their hands on one of its overpriced products. People love to justify their purchase of iPhones by appealing to the superior security of iOS compared to Android. But recent updates have significantly closed the security gap between Android phones and iPhones.

After a month of thinking about it, I still couldn’t rationalize why anyone would spend a night sleeping outside an Apple store to get their hands on one of its overpriced products

Unfortunately, there are no independent studies about what motivates most people to buy Apple phones, but I suspect that security probably wouldn’t top the list. Besides, as the fallout between the FBI and Apple over backdoors reminded us, there’s no such thing as an unhackable device. In fact, there’s a relatively cheap hacking tool that can be used by cops to bypass iPhone encryption. Even when Apple tried to fix this with a patch, iPhones got hacked again anyway. C’est la vie!

Okay, but what about Macs? Apple’s laptops and desktop computers are usually adored for their performance specs and native applications that are geared toward creative types (GarageBand, iMovie, etc.). Apple knows this, which is why a recent commercial campaign for MacBook features artists making art while a Daniel Johnston song called “Story of an Artist” plays in the background. Very subtle. The thing is, you can build a custom PC that matches or surpasses the technical specs of a high-end Mac without spending $5,000.

Despite what you may have heard, building a custom PC is not as hard as it sounds. It’s basically just an expensive and delicate form of electronic Lego. I don’t have any formal experience in computer science and I was able to build a decent PC with 2 GPUs, 16 gigs of memory, two terabytes of storage, and a quad-core CPU for around $1,000 by using handy tools such as PC Part Picker. My PC has way more power than I’ve ever needed and still costs less than a new MacBook and far less than a Mac desktop. As for the Mac’s native applications, most of these have fine Linux equivalents. For example, here’s an extensive list of free sound and MIDI software for Linux; Ubuntu Studio is great for most video editing needs; there are even several open source alternatives to Siri.

HOW TO QUIT AMAZON

Depending on how you look at it, Amazon is either the hardest or the easiest company to quit of the Big Five. On the one hand, its consumer-facing business is mostly predicated on the idea of convenience, as evidenced by products like the Dash button or Alexa. This should, in principle, make it easy to quit since it would only require going back to the old ways of buying things from an actual brick-and-mortar store or visiting websites that sell specific goods.

When I started my experiment, I had an Amazon Prime account, but really only used Amazon to regularly buy three things: Books, cat food, and cat litter. As someone who exclusively uses public transportation, these items are a pain to buy at a store and transfer to my house because they are large and heavy. Of course I could just order the cat products from another site, but Amazon Prime offers free shipping and the ability to set up recurring automatic orders.

Read More: How To Get Amazon Prime for Free for Life

During my experiment, however, I was determined to patronize my locally owned pet store since this seemed to be the most antithetical to Amazon’s dominance of all things retail. Carrying these items the few blocks to my house sucked (a box of cat litter weighs 40 pounds), but what blew even more was the price difference. The same cat food I always buy on Amazon cost more than twice as much at my local pet store. While this was fine for a month, I couldn’t afford this large of an increase in my expenses in the long term. My best bet, then, would be to still buy the pet items I needed online from websites such as Chewy, which still provide most of the convenience offered by Amazon.

It wasn’t convenience alone that made Amazon into the behemoth it is today—there were plenty of online book retailers around when Amazon hit the scene in 1994. What made Amazon successful was that its catalog included books not carried by other (online) bookstores. Over the past two decades, it has expanded this logic to every type of consumer good and this is precisely what makes “the everything store” so difficult to quit.

Whereas a brick-and-mortar store can only carry a finite inventory, Amazon’s inventory is effectively limitless. This combination of infinite selection and total convenience is exactly the type of selling point that appeals to America’s workforce, which is increasingly strapped for both time and money. For people living in rural areas or with disabilities, Amazon’s rapid delivery services can also be a lifeline.

I am able-bodied and live in one of the largest cities in the world, so quitting Amazon is arguably a privilege. I didn’t mind calling my local bookstore to ask it to order a particular title or popping into the local pet store every few weeks if that’s what it took to cut the company from my life.

Then one day I was making a recipe that called for pine nuts, only to discover that none of the three grocery stores in my neighborhood carried them. The only other grocery store remotely close to me was Whole Foods, which was recently acquired by Amazon and definitely carried pine nuts. So I caved, dear reader, and bought some overpriced seeds from an Amazon subsidiary.

Although shopping local or going to other online stores is an option for quitting Amazon, some of its other subsidiaries are far more difficult to replace because they are unique. I don’t game, but if I did it would be hard to find an adequate replacement for Twitch because so many gamers already use it. Likewise, the Internet Movie Database for movie facts and Goodreads for book reviews are two online destinations for which there isn’t an adequate alternative and are basically the go-to sites for their respective domains. Finally, as mentioned earlier, many major websites such as Netflix and Spotify run on Amazon Web Services, so if you use these services you’re also indirectly supporting Amazon.

Nevertheless, there are plenty of good reasons to limit your patronage of Amazon and its subsidiaries. For starters, Amazon has become notorious for its mistreatment of workers. A 2015 New York Times expose detailed the grueling expectations placed on Amazon’s white collar workers, and story after story after story keeps bubbling up that details the inhumane conditions faced by Amazon’s warehouse employees.

You may also take issue with Amazon’s development of facial recognition software that is used for predictive policing and the company’s support of similar products made by companies such as Palantir that use its cloud hosting service. Even if Amazon’s Echo and Dot are ostensibly benign, they are also liable to be hacked and turned into spy devices.

Finally, Amazon has developed a reputation for steamrolling local economies and may end up killing over 2 million jobs as it increases its dominance over traditional retail and other market sectors.

HOW TO QUIT MICROSOFT

I have used Microsoft’s operating system for as long as I can remember. My family’s first computer ran Windows 95, but the first experience I can recall with a computer was Windows 98 and the boot theme must’ve imprinted itself on my impressionable, 5-year-old brain because I’ve exclusively used Windows ever since. The Vista and XP years were rough, I’ll admit, but it’s always darkest before dawn. Windows 10 certainly has its flaws (especially when it comes to privacy), but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t dreading swapping it out for Ubuntu, a popular Linux distribution.

Developed as an open source operating system by Linus Torvalds in the early 90s, Linux has grown from a nerdy curiosity to a defining feature of modern computer systems. Indeed, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook are all major donors to the Linux foundation, which underscores their reliance on the kernel. These days the Linux kernel powers around 75 percent of cloud platforms and is also found at the core of many consumer-facing devices, including every phone using Android, which is the most popular mobile OS in the world by a huge margin.

Although Linux is prized by system admins everywhere for its versatility, it’s been slow to catch on as an operating system for average PC users who mostly use their computers for web browsing, word processing, and other simple tasks. In the beginning, Linux was still very experimental and didn’t offer equivalents for many of the standard programs found on Windows PCs or Macs. Further, many popular programs didn’t bother to create a version of their software that could be used on machines running Linux.

Today, things are much better in this respect. There are Linux equivalents of everything from Microsoft Office to Adobe’s Photoshop, and popular applications such as Spotify usually offer a Linux version of their software.

Prior to this experiment, my only experience with Linux was setting up a cryptocurrency mining rig that ran a custom operating system called EthOS specifically designed for mining. This familiarized me with some basic terminal commands, but really I was a total Linux noob.

Fortunately, getting Linux up and running on my laptop and home PC was pretty easy. For the laptop, I used a colleague’s 2010 Alienware gaming laptop. Rather than partitioning the hard drive, which is a way to have multiple operating systems on a single computer, I opted to erase Windows and have the laptop only run Ubuntu.

To do this, I downloaded Ubuntu (there are plenty of different Linux distributions to choose from, but Ubuntu is one of the most popular distros for casual users) onto a USB drive. If you wanted to try Linux before fully committing to replacing your OS with it, it is possible to run any distribution from a thumb drive. Since I was going to be doing this experiment for a month and wanted to have access to the computer’s storage space, I opted to wipe the computer and install Linux.

On my home PC, I have two terabytes of hard drive space, so I had more than enough room to host two operating systems side by side and still have a decent amount of storage allocated to each OS. When partitioning a disk to run both Windows/MacOS and Linux on the same computer, you can choose how much of your hard drive you want to allocate to each OS. In my case I chose to split it evenly. Now, whenever I reboot that PC, it will automatically boot into Windows, but if I enter the boot menu after restarting the computer, I can also choose to boot into Linux instead.

In spite of the easy of installation and compatibility with most software programs, Ubuntu and other Linux operating systems still haven’t really taken off in the mainstream. The reason for this, I think, is that using Linux actually feels like using a computer—as in, the remarkably complex network of transistors, logic gates, and the other stuff ensconced whatever device you’re reading this on. Linux violates the first rule of getting people to use a technology, which is that it shouldn’t feel like you’re using technology at all. To paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke, it should feel like magic. Linux does not feel like magic; it feels like a pain in the ass—at least until you’ve figured out how to use a command terminal.

We’ve gotten so accustomed to graphical user interfaces that most of us have forgotten that prior to the mid-80s, most computers didn’t have application icons that could summon advanced programs with a double tap on a mouse. Instead, pulling a document from a file or launching a program required the user to actually enter the desired command as text. The latest version of Ubuntu has a sleek graphical interface that isn’t that much different from what you’d find on Windows or MacOS, but after a few days of learning command terminal it’s hard to go back.

It’s possible to do basically everything from a Linux terminal, but just because it’s possible doesn’t necessarily mean you want to. Learning to effectively use the terminal was definitely the most gratifying part of my experiment. Although I am still a novice, I really liked that it allowed me to tell the computer exactly what I wanted it to do, without having to navigate endless menus or other superfluous features. It felt like I had real control over my computer, as opposed to being forced to use applications based on what the designers thought their users wanted. I also learned a great deal about how an operating system actually works by having to think through directory structures and follow logical sequences of commands.

Still, the first few days of using Linux were incredibly frustrating. It felt like I had to Google—ahem, query on DuckDuckGo—the answer for the simplest things, such as how to download an application. At this point, Ubuntu has a pretty extensive package repository, so many programs you use on a regular basis are probably one-click downloads. But if you want to run a more obscure program, you’re going to have to compile it yourself from the source, which includes learning how to make a directory and all that good stuff.

Other than my initial difficulties with the terminal, the Linux experience with Ubuntu was quite pleasant. There are alternative open source programs for pretty much everything you’d find on a Windows system. For example, LibreOffice is a perfect substitute for Word, Excel, and Powerpoint, GIMP is a more than adequate substitute for Adobe Photoshop for amateur photo editing, and Pidgin is a great instant messaging app. If you absolutely need to run Windows programs on a Linux machine, there’s an app called Wine that will let you do just that.

There are also a number of other “hidden” advantages that come with Linux. For starters, it is arguably the most secure OS—you probably don’t even need an anti-virus program. Ubuntu, along with and other Linux distributions, is generally an ultra-efficient and lean operating system, so if you are using an older computer like I was, you shouldn’t have any trouble running it. Best of all, it’s entirely free. This was a breath of fresh air after using Microsoft, which will charge you an arm and a leg for Windows ($139 for the home edition) and then still more for its defining features, such as Microsoft Office ($70 for a single user home edition).

HOW TO QUIT GOOGLE

Google was without a doubt the hardest company to purge from my life, but for this reason, also the most necessary. I am dependent on Google products for almost everything in my personal and professional life. At work, my editors and I workshop stories in Google docs; our company email system is hosted on Gmail servers; my contact with people at VICE that don’t directly work with Motherboard is almost exclusively through Hangouts; I organize calls with sources on Google Calendar; all my documents and photos are automatically synced to Google Drive; I frequently write about videos I find on YouTube; Google Maps is only way I know how to navigate New York City; Google’s Authenticator app secures many of my most important online accounts; Chrome has been my web browser since it was released a decade ago; and most importantly, my phone, and 75 percent of all the other phones on the planet, run Android, which is mainly developed by Google.

In some cases, Google’s products are far better than anything else out there (Google Maps) or are seemingly irreplaceable because that’s what everyone else uses (YouTube). Yet the real attraction to Google is that all of its products are seamlessly integrated across devices. The idea of unlinking all these vital aspects of my professional and personal life was off-putting, and trying to find adequate replacements for all these services seemed nearly impossible. But I am here to tell you that there is life after Google.

GMAIL

The easiest Google product to ditch was Gmail because there are plenty of good alternative email providers out there. I opted to go with Protonmail, a Swiss email provider that encrypts every email sent through its service. The only downside I noticed was that I used up approximately half of my allotted 500 MB of free storage space in the month.

It is, of course, possible to do a paid subscription and upgrade to get more storage, but this costs significantly more than Gmail’s storage upgrades, which also allows for file hosting through Google Drive. For the sake of comparison, 5 GB of storage on Protonmail costs a little over $5/month, whereas Google charges $2/month for 100 GB. This is the economics of scale at work.

Although it is possible to set up your own email server, this process is quite complex, though there are a few startups that are trying to streamline the process. If you haven’t set up a web server before (more on this below), try doing that first before making the leap to hosting your own email.

Rather than going through the hassle of deleting all my Gmail accounts for a month, I set up my Gmail accounts to automatically forward incoming mail to my new Protonmail accounts, so technically Google was still processing my email. For anyone looking to permanently ditch Gmail you’ll still probably want to forward your emails to your new email account at first so that you don’t end up missing anything important while your contacts catch up to your new email address. Another option is to send out a mass email informing your contacts of your new address.

GOOGLE DRIVE

My professional and personal life is such that I have amassed a substantial collection of documents, voice recordings, photographs, and other digital flotsam. To help keeps tabs on data distributed across several devices and to guard against data loss through hard drive destruction, I used a paid subscription to Google Drive. This got me a whopping 100 GB of storage space on Google’s servers for a couple bucks a month, but the real cost was a substantial loss of privacy. Google automatically scans the contents of its user documents stored on Drive to prevent violations of its terms of service and serve up targeted ads. Up until last year it also scanned personal Gmail accounts.

Although I always had the option of moving my personal documents to a different hosting device or to a local hard drive, this always seemed to be more hassle than it was worth since half of my job takes place in Google Docs, which my editors and I use for collaborative editing. Google Drive was convenient because it allows for collaboration on documents and storage in the same spot.

There are several great alternative cloud hosting services available, but far fewer alternative web services for collaborating on documents. One of the best known open source collaborative editors is Etherpad, which launched in 2008…and was almost immediately acquired by Google.

I opted to try Piratepad, a fork of Etherpad that was created by the Swedish Pirate Party. Although I loved the spirit of Piratepad, its barebones format made editing articles difficult because it was harder to leave comments and make suggestions on articles. Instead, you had to make changes directly in the document.

Moreover, whenever I tried to copy an article from Piratepad into VICE’s content management system, the format was totally wonky and reformatting the article added a substantial amount of time to the publishing process.

The solution my editors and I eventually landed on was far from ideal. I would write an article locally using LibreOffice Writer (the Linux equivalent of Word), send the document in Slack to my editors, who would upload it to Google Drive on their own computers, edit it, re-download it as an ODT file—the file format for text documents in LibreOffice—then send it back to me on Slack for rewrites. Despite how wildly inefficient this was, it allowed for all the editing amenities found in Google Docs without messing with the article’s format. Although this worked well enough for the month, it’s hard to imagine that this would be sustainable long term. As far as I could tell, when it comes to collaborative editing software there’s still no good replacement for Google Docs.

As for the hosting platform, I decided to use NextCloud, an open source fork of the file hosting service ownCloud. I was pleasantly surprised at how intuitive NextCloud’s interface was and how easy it was to integrate across my devices, including my rooted phone. NextCloud is run out of Germany, but because it is open source software, anyone can host their own file storage server locally and not rely on it. This only requires about $40 in set-up costs for a Raspberry Pi, a storage medium such as an external hard drive, and an ethernet cord. This sounds complicated, but there are plenty of easy-to-follow tutorials to set up your own “cloud” storage system at home.

MAPS

There was a point in my life where I knew how to use a compass and read a topological map, but whatever part of my brain was reserved for storing this information started to atrophy the day I discovered Google Maps. This app is, without question, the best map app in existence, which makes sense given how much Google has invested in mapping technology. The company has fleets of cars with cameras mounted on them that roam the world’s streets, but its most important data is anonymously submitted by millions of users whose smartphones deliver movement data to Google as they navigate a city.

At this point I couldn’t locate my own ass without consulting Google Maps, so the prospect of trying to navigate New York City—a city I had moved to only a few months prior—without this cartographic crutch was daunting. Last year, a cartographer named Justin O’Beirne published a fascinating deep dive into why Google’s maps are so good and why every competitor, including Apple, has found Google Maps to be basically impossible to replicate, so I knew going in I was going to experience a serious downgrade in navigation capabilities.

Despite this, there are plenty of alternative map apps to choose from. The three best alternatives, Apple Maps and Waze were off-limits because they are owned by Apple and Google, respectively. (I was also under the impression that Here was still owned by Nokia (Microsoft), but have since learned that it was sold to a consortium of German automakers in 2015.) I remembered the days when MapQuest was still considered the go-to for navigation, so I opted to use its service, figuring it probably got better over the years. If it has, it was hard to tell.

One of the most convenient things about Google Maps is that it integrates various forms of transportation into its directions. You’ll get different directions depending on whether you’re biking, taking a car, walking, or taking the subway. MapQuest, however, only offers driving and walking, which is less than ideal in a city where public transit and biking are major modes of transportation.

Throughout the month, I found myself getting frustrated with little things like having to figure out the crossroads of a subway stop, rather than just typing in the name of the stop to get MapQuest to understand where I was. Likewise, I ended up taking a lot of inefficient bike routes because the MapQuest app couldn’t tell me which streets had bike lanes. There’s something really nice about only having to type in “library” in Google Maps to get directed to New York Public Library a few blocks away. Unless you type out the full “New York Public Library” in MapQuest, you’re liable to get directions to a library in another state.

CHROME

Abandoning Chrome was more of an annoyance than anything. I’ve surfed the web using Google’s browser for a while now after years of being a devoted Firefox user. Although I still had Firefox installed on my laptop, it wasn’t nearly as perfectly tuned as my Chrome settings were. I mostly kept it around to use when I had to visit a site that insisted I turn off my various ad blockers and anti-tracking plugins I use on Chrome. The main reason I left Firefox a few years ago was its lackluster security, which is slowly improving.

Although I also briefly used Opera and Brave for this experiment, I ultimately settled on Firefox as my go-to browser. Opera and Brave are both based on Chromium, the underlying engine for Google’s Chrome browser.

Despite being open source, Firefox is not entirely Google-free, either. For the past decade, Mozilla has had an off-and-on agreement with Google to use its search engine by default, which is quite lucrative for Mozilla. Still, it wasn’t running Google’s engine, so I opted to use it for the majority of my experiment. As far as user experience was concerned, switching to Firefox was hardly a noticeable change.

GOOGLE SEARCH

There are plenty of alternative search engines out there, but the two leading candidates—Bing and Google Search—were off limits. For my experiment, I opted for DuckDuckGo, a privacy-oriented search engine. DuckDuckGo doesn’t track your searches nor serve you targeted ads. It’s hardly any wonder, then, that it is the default search engine for the TOR network.

DuckDuckGo also replicates a lot of features found in Google search, such as autocomplete and a command that allows you to directly search a website through the browser. For instance, if I were to type “!imdb the most unknown,” I’d find myself on IMDB’s page for Motherboard’s first documentary, The Most Unknown. Of course I wouldn’t have done that, however, because IMDB is owned by Amazon.

While I appreciated these features, I couldn’t help but notice a remarkable deterioration in the quality of my search results compared to Google. With Google, I can type in a loose collection of keywords and usually find my desired result. With DuckDuckGo, my searches would have to be painstakingly exact. This made things difficult when I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for, and constantly made me wonder if there were better search results that I wasn’t seeing. In any case, DuckDuckGo was still pretty impressive and it felt good to know I wasn’t being tracked every time I put something in the search bar.

Despite its best intentions and willingness to call Google to task for its monopolizing business practices, DuckDuckGo is not entirely free from the grips of the Big Five. According to the company, DuckDuckGo makes money by serving ads from the Yahoo-Microsoft search alliance. While these ads are based on the search query, rather than data about the user, at least a portion of DuckDuckGo’s revenue comes from Microsoft’s pockets. DuckDuckGo also is part of the Amazon affiliate program, so if you purchase Amazon products using the search engine the company earns a small commission.

YOUTUBE

A significant part of my job involves watching YouTube videos, so I had to figure out a way to still get access to them without routing my traffic through the website. In May, there was a really convenient service around called Hooktube that could do just that. To use HookTube, you simply replaced the “youtube” portion in any YouTube video link with “hooktube.” That’s it. When you used HookTube, you wouldn’t be routing traffic through Google’s servers, giving views to the videos, or seeing any ads.

Of course, all these videos still exist on Google’s servers and HookTube would be useless without them. This is yet another case where there is really no real replacement for YouTube in terms of the sheer amount of content hosted on the site. There are plenty of other video platforms (Vimeo, for example) but they have different—and vastly smaller—video libraries.

I really fell in love with HookTube, but unfortunately the service is no more. As detailed in HookTube’s changelog, on July 16 the service was ended due to increasing pressure from YouTube’s legal team. Although HookTube still exists, its links are routed through Google’s servers.

“HookTube is now effectively just a lightweight version of YouTube and useless to the 90 percent of you primarily concerned with denying Google data and seeing videos blocked by your governments,” the changelog reads. “Rest in pieces.”

In the meantime, others have attempted to make replacement versions of HookTube. Some of these appear to work well, but as HookTube demonstrated, it’s only a matter of time before they attract the attention of YouTube’s legal department. While it’s certainly possible to create an endless array of mirror sites to avoid censorship from internet service providers, similar to how torrenting sites such as Pirate Bay continue to operate despite a crackdown on torrenting, no one appears to have done the same with HookTube yet.

AUTHENTICATOR

If you’re thinking of ditching Google and you use two-factor authentication to secure your accounts, make sure you have your recovery code for every account secured using Google Authenticator. If you do not have these, you will be locked out of your account. I cannot emphasize how important it is to triple check that you have a backup way to get into accounts secured with two-factor authentication when leaving Google.

While I wouldn’t suggest reverting to SMS-based verification, which can be spoofed by attackers, there is a good alternative two-factor authentication service out there called Authy.

Read More: What Is a Two-Factor Authentication Recovery Code?

Authy can be used on any site that supports Authenticator, but it comes with a few distinct advantages, the most notable being that it has multiple-device functionality. Authenticator is tied to a single device, so if you want to use it on your phone and tablet at the same time, you’re out of luck. You’ll have to transfer all of your accounts to the new device.

Authy allows you to have the service on multiple devices, so if you lose your phone and haven’t backed up your seeds like I told you to, you’ll still be able to get back into your devices. (Importantly, you can also disable Authy on the lost device.) Moreover, Authenticator only works on mobile devices, whereas Authy works on desktops and laptops as well.

ANDROID

When I arrived home from the Verizon store with my Samsung Galaxy S3, I immediately set to work trying to figure out how to get Sailfish OS on it. Sailfish is perhaps the last truly independent mobile operating system available—Firefox OS, Windows Phone, and Ubuntu Mobile have all bitten the dust in the past few years. At this point, only about 0.1 percent of all smartphones aren’t running iOS or Android. If I were going to truly ditch Google, I was going to have to ditch Android as well.

Android is nominally “open source,” but it is far from “free open source software” in any meaningful sense. Google has maintained the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) since it acquired Android in 2005. Google’s software engineers are responsible for new releases of the Android operating system.

Android is based on the Linux kernel, the part of an operating system responsible for interfacing with the device’s hardware and managing the computer’s resources such as CPU and RAM. This source code is released for free through AOSP, so anyone can take the Android code made by Google developers and use it to make their own version of Android.

When you buy a phone, the Android OS that comes with it also has a bunch of services grafted on top. These are the Google Mobile Services (GMS) that many users take to be defining features Android: Google search, Maps, Drive, Gmail, and so on. These services are definitely not open source.

So why does this matter if anyone can modify Android code, or “fork” it, any time they want? Even if someone managed to fork Android and clone all its best apps, they’d be hard-pressed to find a manufacturer to build a device for this Android clone. As Ben Edelman, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, explained in a 2016 paper, device manufacturers are free to produce phones running “bare” versions of Android, but this means no Google apps are allowed to be pre-installed on the device.

If the device manufacturer wants to include Google Mobile Services on its Android phones, it must sign a Mobile Application Distribution Agreement that requires it to pre-install certain Google applications in prominent places, such as the phone’s home page. Google search must also be set as the default search provider “for all web access points.” Google also requires that its Network Location Provider service be “preloaded and the default, tracking users’ geographic location at all times and sending that information to Google.”

More troubling is that Google makes all device manufacturers that want to run Google Mobile Services on their devices sign an “Anti-Fragmentation Agreement” (AFA). This is a legal agreement that states the manufacturers won’t fork their own version of Android to run on their devices. As Edelman notes, no copies of this agreement have ever been leaked to the public, even though the existence of the document has been confirmed by Google. This is justified on the grounds that it will ensure that all apps work across all versions of Android, rather than having apps that only work with some Android forks.

Similar limitations bind members of the Open Handset Alliance, a group formed by Google in 2007 to bring together companies committed to developing products that are compatible with Google’s Android. According to Ars Technica, OHA contractually binds members from building non-Google approved devices that run competing Android forks. This is acknowledged by Google in a 2012 blog post: “By joining the Open Handset Alliance, each member contributes to and builds one Android platform, not a bunch of incompatible versions.”

As the venture capitalist Bill Gurley wrote in a particularly prescient blog post from 2009, Google’s tactic ensures it dominates the mobile OS market and drives everyone to use its real money maker—search. The reason search is so valuable is because it can gather data on its users and use it to sell them targeted ads. Android, Gurley writes, is not a “product” because Google is not trying to make a profit on it. Instead, “they want to take any layer that lives between themselves and the consumer and make it free (or even less than free). Google is scorching the Earth for 250 miles around the outside of the castle to ensure that no one can approach it. And best I can tell, they are doing a damn good job of it.”

The results of this tactic speak for themselves. Today, approximately 88 percent of all smartphones on the market run Android, and most of them are running Google’s version of the OS. Nevertheless, Google makes it a point to remind people that Android is open source so any company can put the bare AOSP version on their devices. This is technically true, and a few foolhardy companies have tried.

Perhaps the best cautionary tale is Amazon Fire, which was launched in 2014 on a bare AOSP version of Android. The device was widely panned for lacking Gmail and other basic apps, and Amazon discontinued the device the following year after racking up $170 million in losses and a surplus of $83 million worth of unsold devices.

In recent months, Google has moved to further its grip on uncertified Android devices. Previously, it was possible to buy a bare AOSP phone and side-load Google Play to download other Google apps so you could use it like a normal Google-certified Android. In March, however, Google started to block all uncertified Android from accessing any Google services or apps. The vibrant Android modification community was shit-out-of-luck if it wanted to use any Google services or log into its Google accounts.

In short, that left people with three options:

- If they wanted to use any Google services, they had to use Google-certified Android devices and an unmodified version of Android released by Google.

- They could use a bare AOSP or modified version of AOSP Android, but not access any Google services.

- They could use Sailfish OS, open source mobile operating system that is still being actively developed, but they still wouldn’t be able to use any Google services as applications. (They could still visit Google maps or Gmail through their browser, although the mobile versions of these services are less than stellar.)

I opted to use Sailfish OS, which is why I found myself in a Verizon store in Bushwick downgrading my phone to a Samsung Galaxy S3. The Sailfish OS is developed by Jolla, a small Finnish company that was started in 2012 by a group of former Nokia developers who jumped ship just prior to Nokia’s acquisition by Microsoft.

Initially, Jolla aspired to create an alternative phone that would pair with its open source, alternative operating system. Yet after years of setbacks and failed launches, it scaled back its ambitions to work exclusively on Sailfish.

Jolla has recently changed its focus to enterprise customers, but a small dedicated group of die-hard Sailfish fans have kept the consumer Sailfish OS alive and continue to drive its development.

Read More: Meet Sailfish, the Last Independent Mobile Operating System

Motherboard Editor-in-Chief Jason Koebler had a Nexus 5 that he had flashed with Sailfish. Before the experiment began I messed around with it a bit to familiarize myself with the operating system. I liked Sailfish a lot—its interface was close enough to Android to be familiar, but had enough idiosyncrasies to make it distinct. The most noticeable difference is that Sailfish is far more gesture-oriented.

Although Sailfish is an open source, alternative OS, you’re not limited to open source apps. Sailfish supports Android apps, which can be side-loaded onto the phone by downloading the app’s APK file from the internet and loading it onto the phone manually. Still, Jolla’s documentation for Sailfish says, “We always advise against installing Google Services on SailfishOS, as it is known to potentially cause a multitude of problems ranging from serious to trivial.”

Despite really liking Sailfish, I was ultimately unable to use the operating system for my experiment. I couldn’t use Jason’s phone because, though the Nexus 5 was manufactured by LG, it was developed in partnership with Google.

Although Samsung has recently embraced the Android modification community and there’s plenty of documentation available for how to install Sailfish on a Samsung Galaxy S3, Verizon does everything in its power to make sure its customers can’t get root access to its devices.

Verizon and other carriers, such as AT&T, have emerged as the biggest threat to the modification of mobile operating systems in the US by shipping all their phones with locked bootloaders. A bootloader is low-level software that is the first thing to start up when you turn on your phone. It makes sure all the software is working properly and in certain cases prevents users from installing unauthorized software.

Locked bootloaders prevent users from gaining the type of deep access to their phone to be able to swap out a stock Android OS for custom operating systems. Ironically, Microsoft’s Nokia phones and Google’s Nexus and Pixel phones make it super easy to unlock the bootloader on many carriers and are thus easy to customize. This isn’t the case with any phone on Verizon’s network. (Enterprising Android modders have figured out how to unlock the bootloader for some Verizon Android phones, but these are few and far between.)

After days of trying and failing to unlock my bootloader to flash Sailfish OS onto my Samsung Galaxy S3, I admitted defeat. Instead, I opted to run SuperLite, a lightweight version of Android, a ROM developed as part of the Android Open Kang Project (AOKP). (“Kang” is developer slang for stolen code.) AOKP is free open source software based on the official AOSP releases, but it is modified with third-party code contributed by the AOKP community and gives its users even more control over how the Android software interacts with their phone’s hardware.

Since I was unable to unlock my bootloader, I couldn’t “flash” a new ROM to my phone, which would have completely removed the stock Android version and replaced it with a custom ROM of my choice. Instead, I had to install the SuperLite AOKP ROM side-by-side with the stock version. Once it was installed, I could choose which version of the Android I wanted to boot into—basically the equivalent of partitioning your hard drive on a laptop or desktop.

The first step to do this is to enable developer mode in from the Android settings menu. Then, I downloaded and installed the file for a custom recovery system. In my case, I opted for Team Win Recovery (TWRP), one of the most popular recovery systems among Android modders. Once I had installed this on my phone (I just plugged my phone into my computer’s USB port and dragged the TWRP file to the SD card in my phone) I booted into the phone’s recovery mode and restarted my phone.

Next it was time to install the SuperLite AOKP ROM. After installing the SuperLite ROM on my phone’s SD card, I rebooted the phone. From the TWRP menu, select the “Boot Options” menu and then “ROM-Slot-1.” Select the option to create the new ROM slot. Once the ROM slot is created, go back to the main TWRP menu, select the “Install” option and then the zip file for the AOKP ROM you want to install. This will install the AOKP ROM on the ROM slot you just created. Once it’s done installing, reboot the phone and you should boot into the custom AOKP ROM.

It’s worth mentioning here, I think, just how much of a pain in the ass this was for someone who was unfamiliar with the process of rooting phones. Although most of my problems ended up being because of my phone’s locked bootloader, it still took several nights of trial and error to figure out what was going wrong and how to fix it. Ultimately, my difficulties with flashing various ROMs would delay the start of the experiment by several days.

So what was life like using a bare bones, AOKP version of Android without Google? Overall, I didn’t notice much of a difference. I could still link my Protonmail to my phone as well as my cloud storage through NextCloud. I side-loaded Spotify and Lyft by downloading their APK files from the internet and moving them to my phone. (I later learned that Lyft uses Google Maps and so was limited to using Uber.) The only real difference was when it came to using maps, as I mentioned above.

POST MORTEM: 6 MONTHS LATER

It’s now been six months since I finished my experiment, which was plenty of time to see which Big Five services crept back into my life. I resumed using pretty much every Google product the day after the experiment ended. This was mostly due to the nature of my job, which depends on access to my company Gmail account and collaborative editing in Google Docs.

Yet even in my personal life I continue to use Google Maps, Google Drive, and Google Search, although I try to limit my personal searches to DuckDuckGo as often as possible.

In June I also upgraded my phone to a Samsung Galaxy S7, which is currently running the latest version of Android.

A few months after the experiment ended, I swapped out my crappy laptop at work for a homebrew PC. If there was ever a time to fully make the transition to Linux, this was it, and yet I still found myself paying for Windows 10 and partitioning my drive so I could have access to each OS. Old habits die hard, but I now use the terminal in Windows quite regularly whereas before I didn’t use it at all.

Although I still use Amazon on occasion I have ended my Prime subscription and make a point of shopping local or buying from alternative websites whenever possible. So far, this change hasn’t made any noticeable difference on my quality of life.

I still think Apple is a ripoff and Facebook continues to get pwned by lawmakers for its mishandling of user data and disinformation. After I left Facebook, however, I found that I liked being off of social media so much that I also deactivated my only other social media account—Twitter. I have often heard that leaving Twitter when you work in media is a recipe for career suicide. For journalists who depend on it as a tool, this may very well be true. In my case, however, I’ve found that now that I have excised social media from my life I am far less stressed and have a lot more free time. I read more books and devote more time to my actual hobbies rather than scrolling endlessly through timelines.

It’s hard to say whether this experiment could scale to the point of becoming a sustainable way of existing. It was a success insofar as it is definitely possible to use open source replacements for pretty much every major service offered by the Big Five. It was a failure in that it was slightly less convenient and often resulted in an burden on others who were still using the Big Five services, such as my editors.

There was also something of a social burden, too, since I wasn’t able to use most major messaging apps. This was mostly a problem when it came to WhatsApp, which I use for international communication. Within the US, however, relying solely on SMS wasn’t an issue. Although it seemed like leaving Facebook would put a dent in my social life, this remained pretty much the same.

Finally, the experiment failed in the sense that I had to make compromises during the experiment, such as visiting websites hosted on Amazon Web Services or using an AOKP version of Android instead of Sailfish.

I’m certainly not the first person to forsake the Big Five and I’m sure I won’t be the last. There are dedicated communities of people who are determined to not use Google at any cost, however they remain the “preppers” of online life. This raises a disturbing question, however. Is a widespread migration to alternative services possible or, for that matter, even desirable?

It is certainly possible in principle, but a lot would have to change before the mass adoption of alternative services became realistic. Society would have to create the infrastructure for a more sustainable open source ecosystem. As Nadia Eghbal details in the report Roads and Bridges , free and open source software is built on the back of unseen and often unpaid labor. Some of the most popular open source projects in the world are developed and maintained by a few dedicated individuals. If we really care about their projects, we need to find a better way to support their work, other than relying on their goodwill. No one is really incentivized to keep these projects afloat, even if they’re found at the core of many Big Five services.

Whether ditching Big Five services is desirable is a much more difficult question to answer. There is no question that each of the Big Five companies has built incredibly valuable tools that have fundamentally changed the world. The reason most of us would be reluctant to abandon these tools is because they are usually free, useful, and convenient. Yet we are quickly learning the hidden costs of this digital convenience.

Since starting this experiment, #Deletefacebook has grown from a small protest to a sustained and widespread boycott. Google is now facing scrutiny from US and European regulators for mishandling data and monopolization, as well as its work on a censored search engine for China. Amazon continues to be criticized for its treatment of employees, reliance on government tax breaks and handouts, and willingness to sell surveillance tools to law enforcement agencies. Apple is in the middle of a US Supreme Court case about whether it used unlawful business tactics to monopolize its app store.

The social value of the tools developed by the Big Five is what we make of them—they are neither good nor evil by default. As DuckDuckGo demonstrated, it’s possible to create a great search engine that is still supported by ads, but doesn’t harvest user data. Linux has shown that its possible to make an incredibly robust operating system by drawing on the talents of thousands of developers. Android hackers have illustrated no lack of creativity when it comes to pushing the boundaries of what is possible with mobile operating systems, only to be thwarted by Google’s insistence on total control.

Perhaps our lawmakers will be able to reign in the worst inclinations of the titans of Silicon Valley. Or maybe people will get so fed up with the overreach of the Big Five that they will seek alternative services on their own, which seems far more unrealistic to me, given the general lack of understanding about how these companies operate and why it matters.

Nevertheless, I think it is a highly instructive experience to try to see how many Big Five services you can cut from your life, even if it’s just for a few days. Not only will you learn a lot about how servers, personal computers, and mobile phones work, but you might find some open source replacements better than what you were using before.

The important thing is to realize that none of these services are necessary. We may have come to develop a deep reliance on them, but that’s not the same thing. Being an “Apple person” or a “Windows person” is a marketing gimmick, not a personality trait. Amazon is just a version of Walmart that collaborates with cops. Your community existed before Facebook. Google wasn’t always a verb. We have the ability to change these companies by the way we interact with them—but only if we want to.