Do we know how tetanus shots work? The medical establishment holds a view that a tetanus shot prevents tetanus, but how do we know this view is correct?

The cure for tetanus, a life-threatening and often deadly disease, has been sought from the very inception of the modern field of Immunology. The original horse anti-serum treatment of tetanus was developed in the late 19th century and introduced into clinical practice at the time when a bio-statistical concept of a randomized placebo-controlled trial (RCT) did not yet exist. The therapy was infamous for generating a serious adverse reaction called “serum sickness” attributed to the intolerance of humans to horse-derived serum. To make this tetanus therapy usable, it was imperative to substitute the animal origin of anti-serum with the human origin. But injecting a lethal toxin into human volunteers as substitutes for horses would have been unthinkable.

A practical solution was found in 1924: pre-treating the tetanus toxin with formaldehyde (a fixative chemical) made the toxin lose its ability to cause clinical tetanus symptoms. The formaldehyde-treated tetanus toxin is called the toxoid. The tetanus toxoid can be injected into human volunteers to produce a commercial human therapeutic product from their sera called tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG), a modern substitute of the original horse anti-serum. The tetanus toxoid has also become the vaccine against clinical tetanus.

The tetanus toxin, called tetanospasmin, is produced by numerous C. tetani bacterial strains. C. tetani normally live in animal intestines, notably in horses, without causing tetanus to their intestinal carriers. These bacteria require anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions to be active, whereas in the presence of oxygen they turn into resilient but inactive spores, which do not produce the toxin. It has been recognized that inactive tetanus spores are ubiquitous in the soil. Tetanus can result from the exposure to C. tetani via poorly managed tetanus-prone wounds or cuts, but not from oral ingestion of tetanus spores. Quite to the contrary, oral exposure to C. tetani has been found to build resistance to tetanus without carrying the risk of disease, as described in the section on “Natural Resistance to Tetanus.”

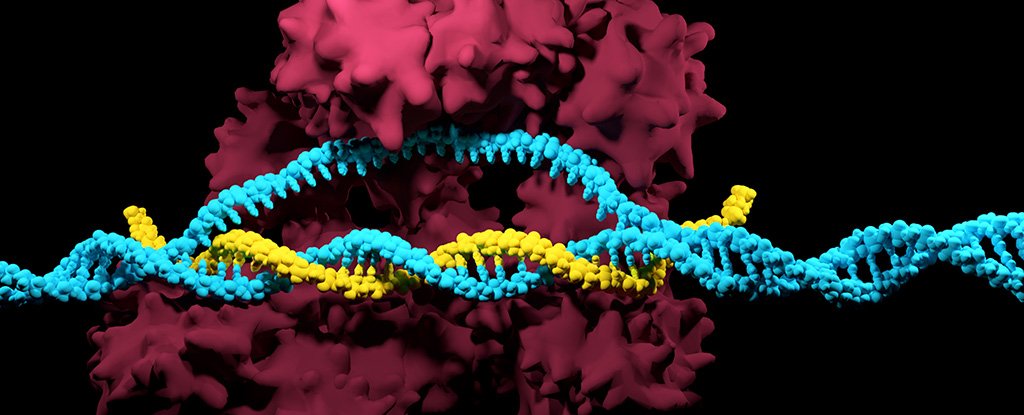

Once secreted by C. tetani germinating in a contaminated wound, tetanospasmin diffuses through the tissue’s interstitial fluids or bloodstream. Upon reaching nerve endings, it is adsorbed by the cell membrane of neurons and transported through nerve trunks into the central nervous system, where it inhibits the release of a neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). This inhibition can result in various degrees of clinical tetanus symptoms: rigid muscular spasms, such as lockjaw, sardonic smile, and severe convulsions that frequently lead to bone fractures and death due to respiratory compromise.

Curative effects of the anti-serum therapy as well as the preventative effects of the tetanus vaccination are deemed to rely upon an antibody molecule called antitoxin. But the assumption that such antitoxin was the sole “active” ingredient in the original horse anti-serum has not been borne out experimentally. Since horses are natural carriers of tetanus spores, their bloodstream could have contained other unrecognized components, which got harnessed in the therapeutic anti-serum. “Natural Resistance to Tetanus” discusses other serum entities detected in research animals carrying C. tetani, which better correlated with their protection from clinical tetanus than did serum antitoxin levels. Nevertheless, the main research effort in the tetanus field remained narrowly focused on antitoxin.

Antitoxin molecules are thought to inactivate the corresponding toxin molecules by virtue of their toxin-binding capacity. This implies that to accomplish its protective effect, antitoxin must come into close physical proximity with the toxin and combine with it in a way that would prevent or preempt the toxin from binding to nerve endings. Early research on the properties of a newly discovered antitoxin was done in small-sized research animals, such as guinea pigs. The tetanus toxin was pre-incubated in a test tube with the animal’s serum containing antitoxin before being injected into another (antitoxin-free) animal, susceptible to tetanus. Such pre-incubation made the toxin lose its ability to cause tetanus in otherwise susceptible animals — i.e. the toxin was neutralized.

Nevertheless, researchers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were baffled by a peculiar observation. Research animals, whose serum contained enough antitoxin to inactivate a certain amount of the toxin in a test tube, would succumb to tetanus when they were injected with the same amount of the toxin. Furthermore, it was noted that the mode of the toxin injection had a different effect on the ability of serum antitoxin to protect the animal. The presence of antitoxin in the serum of animals afforded some degree of protection against the toxin injected directly into the bloodstream (intravenously). However, when the toxin was injected into the skin it would be as lethal to animals containing substantial levels of serum antitoxin as to animals virtually free of serum antitoxin.[1]

The observed difference in serum antitoxin’s protective “behavior” was attributed to the toxin’s propensity to bind faster to nerve cells than to serum antitoxin. The pre-incubation of the toxin with antitoxin in a test tube, or the injection of the toxin directly into the bloodstream, where serum antitoxin is found, gives antitoxin a head start in combining with and neutralizing the toxin. However, a skin or muscle injection of the toxin does not give serum antitoxin such a head start.

Researchers in the 21st century have developed an advanced fluorescent labeling technique to track the uptake of the injected tetanus toxin into neurons. Using this technique, researchers examined the effect of serum antitoxin, which was induced by vaccinating mice with the tetanus toxoid vaccine ahead of time (the same one currently used in humans), on blocking the neuronal uptake and transport of the tetanus toxin fragment C (TTC) to the brain from the site of intramuscular injection. Vaccinated and non-vaccinated animals showed similar levels of TTC uptake into the brain. The authors of the study concluded that the “uptake of TTC by nerve terminals from an intramuscular depot is an avid and rapid process and is not blocked by vaccination.”[2] They have further commented that their results appear to be surprising in view of protective effects of immunization with the tetanus toxoid. Indeed, the medical establishment holds a view that a tetanus shot prevents tetanus, but how do we know this view is correct?

Neonatal Tetanus

Neonatal tetanus is common in tropical under-developed countries but is extremely rare in developed countries. This form of tetanus results from unhygienic obstetric practices, when cutting the umbilical cord is performed with unsterilized devices, potentially contaminating it with tetanus spores. Adhering to proper obstetric practices removes the risk of neonatal tetanus, but this has not been the standard of birth practices for some indigenous and rural people in the past or even present.

The authors of a neonatal tetanus study performed in the 1960s in New Guinea describe the typical conditions of childbirth among the locals:

“The mother cuts the cord 1 inch (2.5 cm) or less from the abdominal wall; it is never tied. In the past she would always use a sliver of sago bark, but now she uses a steel trade-knife or an old razor blade. These are not cleaned or sterilized in any way and no dressing is put of the cord. The child lies after birth on a dirty piece of soft bark, and the cut cord can easily become contaminated by dust from the floor of the hut or my mother’s feces expressed during childbirth, as well as by the knife and her finger.”[3]

Not surprisingly, New Guinea had a high rate of neonatal tetanus. Because improving birth practices seemed to be unachievable in places like New Guinea, subjecting pregnant women to tetanus vaccination was contemplated by public health authorities as a possible solution to neonatal tetanus.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) assessing the effectiveness of the tetanus vaccine in preventing neonatal tetanus via maternal vaccination was conducted in the 1960s in rural Colombia in a community with high rates of neonatal tetanus.[4] The design of this trial has been recently reviewed by the Cochrane Collaboration for potential biases and limitations and, with minor comments, has been considered of good quality for the purposes of vaccine effectiveness (but not safety) determination.[5] The trial established that a single dose of the tetanus vaccine given before or during pregnancy had a partial effect on preventing neonatal tetanus in the offspring: 43% reduction was observed in the tetanus vaccine group compared to the control group, which instead of the tetanus shot received a flu shot. A series of two or three tetanus booster shots, given six or more weeks apart before or during pregnancy, reduced neonatal tetanus by 98% in the tetanus vaccine group compared to the flu shot control group. The duration of the follow up in this trial was less than five years.

In addition to testing the effects of vaccination, this study has also documented a clear relationship between the incidence of neonatal tetanus and the manner in which childbirth was conducted. No babies delivered in a hospital, by a doctor or a nurse, contracted neonatal tetanus regardless of the mother’s vaccination status. On the other hand, babies delivered at home by amateur midwives had the highest rate of neonatal tetanus.

Hygienic childbirth appears to be highly effective in preventing neonatal tetanus and makes tetanus vaccination regimen during pregnancy unnecessary for women who give birth under hygienic conditions. Furthermore, it was estimated in 1989 in Tanzania that 40% of neonatal tetanus cases still occurred in infants born to mothers who were vaccinated during pregnancy,[6] stressing the importance of hygienic birth practices regardless of maternal vaccination status.

Tetanus In Adults

Based on the protective effect of maternal vaccination in neonatal tetanus, demonstrated by an RCT and discussed above, we might be tempted to infer that the same vaccine also protects from tetanus acquired by stepping on rusty nails or incurring other tetanus-prone injuries, when administered to children or adults, either routinely or as an emergency measure. However, due to potential biologic differences in how tetanus is acquired by newborns versus by older children or adults, we should be cautious about reaching such conclusions without first having direct evidence for the vaccine effectiveness in preventing non-neonatal tetanus.

It is generally assumed that the tetanus toxin must first leach into the blood (where it would be intercepted by antitoxin, if it is already there due to timely vaccination) before it reaches nerve endings. This scenario is plausible in neonatal tetanus, as it appears that the umbilical cord does not have its own nerves.[7] On the other hand, the secretion of the toxin by C. tetani germinating in untended skin cuts or in muscle injuries is more relevant to how children or adults might succumb to tetanus. In such cases, there could be nerve endings near germinating C. tetani, and the toxin could potentially reach such nerve endings without first going through the blood to be intercepted by vaccine-induced serum antitoxin. This scenario is consistent with the outcomes of the early experiments in mice, discussed in the beginning.

Although a major disease in tropical under-developed countries, tetanus in the USA has been very rare. In the past, tetanus occurred primarily in poor segments of the population in southern states and in Mexican migrants in California. It was swiftly diminishing with each decade prior to the 1950s (in the pre-vaccination era), as inferred from tetanus mortality records and similar case-fatality ratios (about 67-70%) in the early 20th century[8] versus the mid-20th century).[9] The tetanus vaccine was introduced in the USA in 1947 without performing any placebo-controlled clinical trials in the segment of the population (children or adults), where it is now routinely used.

The rationale for introducing the tetanus vaccine into the U.S. population, at low overall risk for tetanus anyway, was simply based on its use in the U.S. military personnel during World War II. According to a post-war report:[10]

- the U.S. military personnel received a series of three injections of the tetanus toxoid, routine stimulating injection was administered one year after the initial series, and an emergency stimulating dose was given on the incurrence of wounds, severe burns, or other injuries that might result in tetanus;

- throughout the entire WWII period, 12 cases of tetanus have been documented in the U.S. Army;

- in World War I there were 70 cases of tetanus among approximately half a million admissions for wounds and injuries, an incidence of 13.4 per 100,000 wounds. In World War II there were almost three million admissions for wounds and injuries, with a tetanus case rate of 0.44 per 100,000 wounds.

The report leads us to conclude that vaccination has played a role in tetanus reduction in wounded U.S. soldiers during WWII compared to WWI, and that this reduction vouches for the tetanus vaccine effectiveness. However, there are other factors (e.g. differences in wound care protocols, including the use of antibiotics, higher likelihood of wound contamination with horse manure rich in already active C. tetani in earlier wars, when horses were used by the cavalry, etc.), which should preclude us from uncritically assigning tetanus reduction during WWII to the effects of vaccination.

Severe and even deadly tetanus is known to occur in recently vaccinated people with high levels of serum antitoxin.[11] Although the skeptic might say that no vaccine is effective 100% of the time, the situation with the tetanus vaccine is quite different. In these cases of vaccine-unpreventable tetanus, vaccination was actually very effective in inducing serum antitoxin, but serum antitoxin did not appear to have helped preventing tetanus in these unfortunate individuals.

The occurrence of tetanus despite the presence of antitoxin in the serum should have raised a red flag regarding the rationale of the tetanus vaccination program. But such reports were invariably interpreted as an indication that higher than previously thought levels of serum antitoxin must be maintained to protect from tetanus, hence the need for more frequent, if not incessant, boosters. Then how much higher “than previously thought” do serum levels of antitoxin need to be to ensure protection from tetanus?

Crone & Reder (1992) have documented a curious case of severe tetanus in a 29-year old man with no pre-existing conditions and no history of drug abuse, typical among modern-day tetanus victims in the USA. In addition to the regular series of tetanus immunization and boosters ten years earlier during his military service, this patient had been hyper-immunized (immunized with the tetanus toxoid to have extremely high serum antitoxin) as a volunteer for the purposes of the commercial TIG production. He was monitored for the levels of antitoxin in his serum and, as expected, developed extremely high levels of antitoxin after the hyper-immunization procedure. Nevertheless, he incurred severe tetanus 51 days after the procedure despite clearly documented presence of serum antitoxin prior to the disease. In fact, upon hospital admission for tetanus treatment his serum antitoxin levels measured about 2,500 times higher than the level deemed protective. His tetanus was severe and required more than five weeks of hospitalization with life-saving measures. This case demonstrated that serum antitoxin has failed to prevent severe tetanus even in the amounts 2,500 times higher than what is considered sufficient for tetanus prevention in adults.

The medical establishment chooses to turn a blind eye to the lack of solid scientific evidence to substantiate our faith in the tetanus shot. It also chooses to ignore the available experimental and clinical evidence that contradicts the assumed but unproven ability of vaccine-induced serum antitoxin to reduce the risk of tetanus in anyone other than maternally-vaccinated neonates, who do not even need this vaccination measure when their umbilical cords are dealt with using sterile techniques.

Ascorbic Acid In Tetanus Treatment

Anti-serum is not the only therapeutic measure tried in tetanus treatment. Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) has also been tried. Early research on ascorbic acid has demonstrated that it too could neutralize the tetanus toxin.[12]

In a clinical study of tetanus treatment conducted in Bangladesh in 1984, the administration of conventional procedures, including the anti-tetanus serum, to patients who contracted tetanus left 74% of them dead in the 1-12 age group and 68% dead in the 13-30 age group. In contrast, daily co-administration of one gram of ascorbic acid intravenously had cut down this high mortality to 0% in the 1-12 age group, and to 37% in the 13-30 age group.[13] The older patients were treated with the same amount of ascorbic acid without adjustments for their body weight.

Although this was a controlled clinical trial, it is not clear from the description of the trial in the publication by Jahan et al. whether or not the assignment of patients into the ascorbic acid treatment group versus the placebo-control group was randomized and blinded, which are crucial bio-statistical requirements for avoiding various biases. A more definitive study is deemed necessary before intravenous ascorbic acid can be recommended as the standard of care in tetanus treatment.[14] It is odd that no properly documented RCT on ascorbic acid in tetanus treatment has been attempted since 1984 for the benefit of developing countries, where tetanus has been one of the major deadly diseases. This is in stark contrast to the millions of philanthropic dollars being poured into sponsoring the tetanus vaccine implementation in the Third world.

Natural Resistance To Tetanus

In the early 20th century, investigators Drs. Carl Tenbroeck and Johannes Bauer pursued a line of laboratory research, which was much closer to addressing natural resistance to tetanus than the typical laboratory research on antitoxin in their days. Omitted from immunologic textbooks and the history of immunologic research, their tetanus protection experiments in guinea pigs, together with relevant serological and bacteriological data in humans, nevertheless provide a good explanation for tetanus being a rather rare disease in many countries around the world, except under the conditions of past wars.

In the experience of these tetanus researchers, the injection of dormant tetanus spores could never by itself induce tetanus in research animals. To induce tetanus experimentally by means of tetanus spores (as opposed to by injecting a ready-made toxin, which never happens under natural circumstances anyway), spores had to be premixed with irritating substances that could prevent rapid healing of the site of spore injection, thereby creating conditions conducive to spore germination. In the past, researchers used wood splinters, saponin, calcium chloride, or aleuronat (flour made with aleurone) to accomplish this task.

In 1926, already being aware that oral exposure to tetanus spores does not lead to clinical tetanus, Drs. Tenbroeck and Bauer set out to determine whether feeding research animals with tetanus spores could provide protection from tetanus induced by an appropriate laboratory method of spore injection. In their experiment, several groups of guinea pigs were given food containing distinct strains of C. tetani. A separate group of animals were used as controls—their diet was free of any C. tetani. After six months, all groups were injected under the skin with spores premixed with aleuronat. The groups that were previously exposed to spores orally did not develop any symptoms of tetanus upon such tetanus-prone spore injection, whereas the control group did. The observed protection was strain-specific, as animals still got tetanus if injected with spores from a mismatched strain—a strain they were not fed with. But when fed multiple strains, they developed protection from all of them.

Quite striking, the protection from tetanus established via spore feeding did not have anything to do with the levels of antitoxin in the serum of these animals. Instead, the protection correlated with the presence of another type of antibody called agglutinin—so named due to its ability to agglutinate (clump together) C. tetani spores in a test tube. Just like the observed protection was strain-specific, agglutinins were also strain-specific. These data are consistent with the role of strain-specific agglutinins, not of antitoxin, in natural protection from tetanus. The mechanism thereby strain-specific agglutinins have caused, or correlated with, tetanus protection in these animals has remained unexplored.

In the spore-feeding experiment, it was still possible to induce tetanus by overwhelming this natural protection in research animals. But to accomplish this task, a rather brute force procedure was required. A large number of purified C. tetani spores were sealed in a glass capsule; the capsule was injected under the skin of research animals and then crushed. Broken glass pieces were purposefully left under the skin of the poor creatures so that the gory mess was prevented from healing for a long time. Researchers could succeed in overwhelming natural tetanus defenses with this excessively harsh method, perhaps mimicking a scenario of untended war-inflicted wounds.

How do these experimental data in research animals relate to humans? In the early 20th century, not only animals but also humans were found to be intestinal carriers of C. tetani without developing tetanus. About 33% of tested human subjects living around Beijing, China were found to be C. tetani carriers without any prior or current history of tetanus disease.[15] Bauer & Meyer (1926) cite other studies, which have reported around 25% of tested humans being healthy C. tetani carriers in other regions of China, 40% in Germany, 16% in England, and on average 25% in the USA, highest in central California and lowest on the southern coast. Based on the California study, age, gender, or occupation denoting the proximity to horses did not appear to play a role in the distribution of human C. tetani carriers.

Another study was performed back in the 1920s in San Francisco, CA.[16] About 80% of the examined subjects had various levels of agglutinins to as many as five C. tetani strains at a time, although no antitoxin could be detected in the serum of these subjects. C. tetani organisms could not be identified in the stool of these subjects either. It is likely that tetanus spores were in their gut transiently in the past, leaving serological evidence of oral exposure, without germinating into toxin-producing organisms. It would be important to know the extent of naturally acquired C. tetani spore agglutinins in humans in various parts of the world now, instead of relying on the old data, but similar studies are not likely to be performed anymore.

Regrettably, further research on naturally acquired agglutinins and on exactly how they are involved in the protection from clinical tetanus appears to have been abandoned in favor of more lucrative research on antitoxin and vaccines. If such research continued, it would have given us clear understanding of natural tetanus defenses we may already have by virtue of our oral exposure to ubiquitous inactive C. tetani spores.

Since the extent of our natural resistance to clinical tetanus is unknown due to the lack of modern studies, all we can be certain of is that preventing dormant tetanus spores from germinating into toxin-producing microorganisms is an extremely important measure in the management of potentially contaminated skin cuts and wounds. If this crucial stage of control—at the level of preventing spore germination—is missed and the toxin production ensues, the toxin must be neutralized before it manages to reach nerve endings.

Both antitoxin and ascorbic acid exhibit toxin-neutralizing properties in a test tube. In the body, however, vaccine-induced antitoxin is located in the blood, whereas the toxin might be focally produced in the skin or muscle injury. This creates an obvious physical impediment for toxin neutralization to happen effectively, if at all, by means of vaccine-induced serum antitoxin. Furthermore, no placebo-controlled trials have ever been performed to rule out the concern about such an impediment by providing clear empirical evidence for the effectiveness of tetanus shots in children and adults. Nevertheless, the medical establishment relies upon induction of serum antitoxin and withholds ascorbic acid in tetanus prevention and treatment.

When an old medical procedure of unknown effectiveness, such as the tetanus shot, has been the standard of medical care for a long time, finalizing its effectiveness via a modern rigorous placebo-controlled trial is deemed unethical in human research. Therefore, our only hope for the advancement of tetanus care is that further investigation of the ascorbic acid therapy is performed and that this therapy becomes available to tetanus patients around the world, if confirmed effective by rigorous bio-statistical standards.

Until then, may the blind faith in the tetanus shot help us!

Learn more by reading Tetyana’s groundbreaking and lucid book Vaccine Illusion.

About The Author

Tetyana Obukhanych earned her Ph.D. in Immunology at the Rockefeller University in New York, NY with her research dissertation focused on understanding immunologic memory, perceived by the mainstream biomedical establishment to be key to vaccination and immunity. She was subsequently involved in laboratory research as a postdoctoral research fellow within leading biomedical institutions, such as Harvard Medical School and Stanford University School of Medicine.

Having had several childhood diseases despite being properly vaccinated against them, Dr. Obukhanych has undertaken a thorough investigation of scientific findings regarding vaccination and immunity. Based on her analysis, Dr. Obukhanych has articulated a view that challenges mainstream assumptions and theories on vaccination in her e-book Vaccine Illusion.

Dr. Obukhanych continues her independent in-depth analysis of peer-reviewed scientific findings related to vaccination and natural requirements of the immune system function. Her goal is to bring a scientifically-substantiated and dogma-free perspective on vaccination and natural immunity to parents and health care practitioners. Visit www.naturalimmunityfundamentals.com for more information.

[1] Tenbroeck, C. & Bauer, J.H. The immunity produced by the growth of tetanus bacilli in the digestive tract. J Exp Med 43, 361-377 (1926).

[2] Fishman, P.S., Matthews, C.C., Parks, D.A., Box, M. & Fairweather, N.F. Immunization does not interfere with uptake and transport by motor neurons of the binding fragment of tetanus toxin. J Neurosci Res 83, 1540-1543 (2006).

[3] Schofield, F.D., Tucker, V.M. & Westbrook, G.R. Neonatal tetanus in New Guinea. Effect of active immunization in pregnancy. Br Med J 2, 785-789 (1961).

[4] Newell, K.W., Dueñas Lehmann, A., LeBlanc, D.R. & Garces Osorio, N. The use of toxoid for the prevention of tetanus neonatorum. Final report of a double-blind controlled field trial. Bull World Health Organ 35, 863-871 (1966).

[5] Demicheli, V., Barale, A. & Rivetti, A. Vaccines for women to prevent neonatal tetanus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:CD002959 (2013).

[6] Maselle, S.Y., Matre, R., Mbise, R. & Hofstad, T. Neonatal tetanus despite protective serum antitoxin concentration. FEMS Microbiol Immunol 3, 171-175 (1991).

[7] Fox, S.B. & Khong, T.Y. Lack of innervation of human umbilical cord. An immunohistological and histochemical study. Placenta 11, 59-62 (1990).

[8] Bauer, J.H. & Meyer, K.F. Human intestinal carriers of tetanus spores in California. J Infect Dis 38, 295-305 (1926).

[9] LaForce, F.M., Young, L.S. & Bennett, J.V. Tetanus in the United States (1965-1966): epidemiologic and clinical features. N Engl J Med 280, 569-574 (1969).

[10] Editorial: Tetanus in the United States Army in World War II. N Engl J Med 237, 411-413 (1947).

[11] Abrahamian, F.M., Pollack, C.V., Jr., LoVecchio, F., Nanda, R. & Carlson, R.W. Fatal tetanus in a drug abuser with “protective” antitetanus antibodies. J Emerg Med 18, 189-193 (2000).

Beltran, A. et al. A case of clinical tetanus in a patient with protective antitetanus antibody level. South Med J 100, 83 (2007).

Berger, S.A., Cherubin, C.E., Nelson, S. & Levine, L. Tetanus despite preexisting antitetanus antibody. JAMA 240, 769-770 (1978).

Crone, N.E. & Reder, A.T. Severe tetanus in immunized patients with high anti-tetanus titers. Neurology 42, 761-764 (1992).

Passen, E.L. & Andersen, B.R. Clinical tetanus despite a protective level of toxin-neutralizing antibody. JAMA 255, 1171-1173 (1986).

Pryor, T., Onarecker, C. & Coniglione, T. Elevated antitoxin titers in a man with generalized tetanus. J Fam Pract 44, 299-303 (1997).

[12] Jungeblut, C.W. Inactivation of tetanus toxin by crystalline vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid). J Immunol 33, 203-214 (1937).

[13] Jahan, K., Ahmad, K. & Ali, M.A. Effect of ascorbic acid in the treatment of tetanus. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 10, 24-28 (1984).

[14] Hemilä, H. & Koivula, T. Vitamin C for preventing and treating tetanus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD006665 (2008).

[15] Tenbroeck, C. & Bauer, J.H. The tetanus bacillus as an intestinal saprophyte in man. J Exp Med 36, 261-271 (1922).

[16] Coleman, G.E. & Meyer, K.F. Study of tetanus agglutinins and antitoxin in human serums. J Infect Dis 39, 332-336 (1926).