Summary: Astrocytes play a crucial role in spatial learning, researchers discovered.

Source: University of Bonn

There are two fundamentally different cell types in the brain, neurons and glial cells. The latter, for example, insulate the “wiring” of nerve cells or guarantee optimal working conditions for them.

A new study led by the University of Bonn has now discovered another function in rodents: The results suggest that a certain type of glial cell plays an important role in spatial learning. The German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) was involved in the work.

The results have now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Each place has numerous characteristics that distinguish it and make it unmistakable as a whole. A gnarled tree. A babbling brook at its foot. Fragrant wildflowers in the meadow behind. When we visit a place for the first time, we store this combination of features. When we then encounter the interplay of tree, brook, and wildflower meadow another time, our brain recognizes it: We remember having been there before.

This is made possible by mechanisms such as the so-called dendritic integration of synaptic activity.

“We were able to show that the so-called astroglial cells or astrocytes play an essential role in this integration,” explains Prof. Dr. Christian Henneberger from the Institute of Cellular Neuroscience at the University Hospital Bonn.

“They regulate how sensitive neurons are to a specific combination of features.”

One million place cells in the mouse brain

In their study, the researchers took a close look at neurons in the hippocampus of rodents. The hippocampus is a region in the brain that plays a central role in memory processes.

This is especially true for spatial memory: “In the hippocampus, there are neurons that specialize in just that – place cells,” says Henneberger, who is also a member of the Collaborative Research Center 1089 – where the research project was based – and the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Life & Health” at the University of Bonn.

There are about one million of these place cells in the mouse hippocampus alone. Each responds to a specific combination of environmental characteristics.

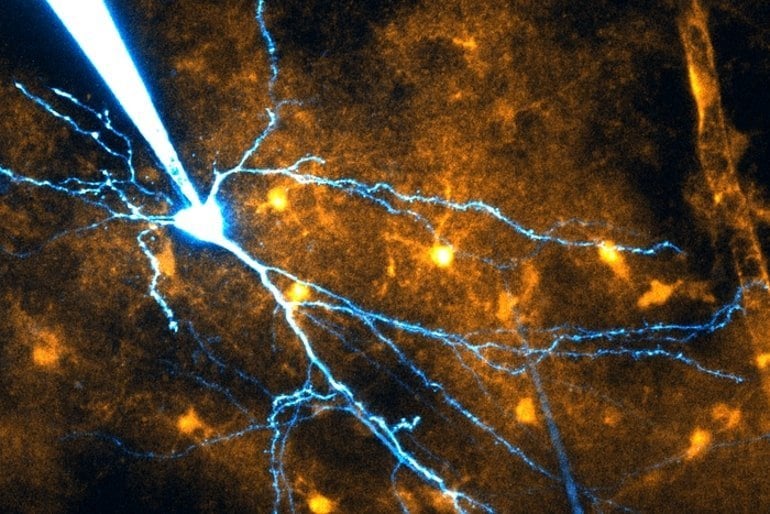

Place cells have long extensions, the dendrites. These are branched like the crown of a tree and dotted with numerous contact points. Information that our senses convey to us about a location arrives here. These contacts are called synapses.

“When signals arrive at many neighboring synapses at the same time, a strong voltage pulse occurs in the dendrite – a so-called dendritic spike,” explains Dr. Kirsten Bohmbach, who performed most of the experiments in the study.

“This process is what we call dendritic integration: The spike only occurs when a sufficient number of synapses are active at the same time. Such spikes travel toward the cell body, where they can trigger another voltage pulse – an action potential.”

Place cells in attention mode

Place cells generate action potentials at regular intervals. The speed at which they do this can vary widely. However, when mice orient themselves in a new environment, their place cells always oscillate in a special rhythm – they then generate five to ten voltage pulses per second.

This rhythm causes the nerve cells to release certain messenger substances. And this is where astrocytes come in: They have sensors to which these messenger substances dock, and in turn release a substance called D-serine.

“The D-serine then migrates to the dendrites of the place cells,” Bohmbach explains. “There, it ensures that the dendritic spikes can develop more easily and are also much stronger.”

When mice are in orientation mode, this makes it easier for them to store and recognize new locations. It is similar to a cab driver concentrating on navigating through the city center and memorizing changing locations. The passenger next to the driver is also looking at the road, but his thoughts are elsewhere and he notices less (however, there are also quite different processes involved in such attention phenomena).

“If we inhibit the assistance provided by astrocytes in mice, they are less likely to recognize familiar places,” Henneberger says. However, this does not apply to locations that are particularly relevant – for example, because they pose a potential danger: These continue to be avoided by the animals.

“The mechanism we discovered therefore controls the threshold at which location information is stored or recognized.”

The results provide a new insight into how memory works and is controlled. In the medium term, they may also help to answer the question of how certain forms of memory disorders develop.

The research results are also an expression of fruitful intra-university cooperation: “They would not have been possible without the intensive collaboration with Prof. Dr. Heinz Beck’s laboratory at the Institute of Experimental Epileptology and Cognitive Sciences and, in particular, his colleagues Dr. Nicola Masala and Dr. Thoralf Opitz,” Henneberger highlights.

Participating institutions and funding:

In addition to the University of Bonn and the University Hospital Bonn, the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) and University College London were involved in the work. The Study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the returnee program of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Abstract

An astrocytic signaling loop for frequency-dependent control of dendritic integration and spatial learning

Dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells amplify clustered glutamatergic input by activation of voltage-gated sodium channels and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). NMDAR activity depends on the presence of NMDAR co-agonists such as D-serine, but how co-agonists influence dendritic integration is not well understood.

Using combinations of whole-cell patch clamp, iontophoretic glutamate application, two-photon excitation fluorescence microscopy and glutamate uncaging in acute rat and mouse brain slices we found that exogenous D-serine reduced the threshold of dendritic spikes and increased their amplitude.

Triggering an astrocytic mechanism controlling endogenous D-serine supply via endocannabinoid receptors (CBRs) also increased dendritic spiking. Unexpectedly, this pathway was activated by pyramidal cell activity primarily in the theta range, which required HCN channels and astrocytic CB1Rs.

Therefore, astrocytes close a positive and frequency-dependent feedback loop between pyramidal cell activity and their integration of dendritic input. Its disruption in mice led to an impairment of spatial memory, which demonstrated its behavioral relevance.