Patients undergoing major abdominal procedures have an independent risk for mortality when at least 6 L of IV fluid are administered on the day of surgery.

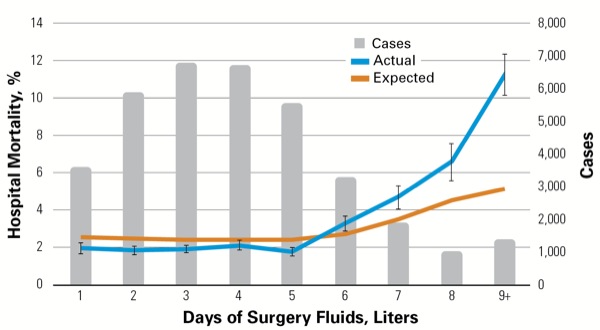

The retrospective study, which used a large administrative database of roughly 36,000 patient discharges from 393 hospitals across the United States, found that patients receiving at least 6 L of IV fluid on the day of surgery had a 48-hour inpatient mortality rate that was 48% higher than expected (Figure).

Overall, 21% of patients received over 6 L of IV fluid on the day of surgery, with 2% of patients receiving at least 9 L. “To me, this finding is provocative,” said Thomas Hopkins, MD, of Duke University Health System, in Durham, N.C. “After rigorously adjusting for patient characteristics like age, comorbidity, acute organ dysfunction and diagnosis, as well as disease-specific factors like procedure, location, surgical approach and duration of procedure, we found that excessive fluid administration was an independent risk factor for perioperative mortality.” The study was presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (abstract A4147).

Dr. Hopkins, who is director of quality improvement in the Department of Anesthesiology and associate medical director of care redesign at Duke, was inspired to conduct the study because of his long-standing interest in enhanced recovery after surgery and his work on enhanced recovery programs (ERPs).

“Our multidisciplinary team here at Duke University Health System found that there are aspects of our ERP that have a differential impact on patient outcomes,” he said. “One of these factors appears to be perioperative fluid administration. Our preliminary data suggest that the way we administer fluid in the operating room and the way that we administer fluid on the surgical wards following the operation can have an impact on perioperative morbidity, length of hospital stay and ultimately on patient survival.”

The current study took the hypothesis generated from these preliminary data and tested it on a much larger patient population to determine whether the trends established at Duke would be applicable across an extremely large data set.

The study’s patient mortality risk was based on hospital practice, with 22% of hospitals having only 5.8% of their cases in the high-risk fluid category, whereas 26% of hospitals had 40.5% of patients in that category. “Therefore, there is clearly significant variation in practice, depending on site of care,” Dr. Hopkins said.

Based on the study, Dr. Hopkins and his colleagues are uncertain as to the distinguishing factors that each of the two hospital groups possesses to cause such disparate results. “But our hypothesis is that the hospitals in the best-performance group have some type of algorithm or protocol or standard approach to fluid management on the day of surgery, whereas hospitals in the underperforming group most likely did not,” he said.

The reflex assumption after reading the results of the study is that less fluid should be administered on the day of surgery, according to Dr. Hopkins. “This idea is not new. We have seen a fair amount of academic work attempting to elucidate the answer to this question over the past five years,” he said. However, a number of large retrospective analyses have concluded that “if you simply restrict fluid on the day of surgery, you can do harm. In fact, there is probably a bimodal distribution of patient morbidity and mortality that is associated with either too little or too much fluid on the day of surgery,” he said.

Hence, based on the literature and the present study, “the best solution is to consider a dynamic approach to perioperative volume resuscitation that leverages a patient-specific and a patient-tailored strategy,” Dr. Hopkins said.

Dr. Hopkins emphasized it is extremely important to stress that one-fifth of the surgical patient population for major abdominal surgeries in the United States could be at increased risk for perioperative mortality “because our current approach to fluid resuscitation in this patient population is very unstructured. We know there is a significant amount of variability in our practice.”

Dr. Hopkins is optimistic that the study will spur a reassessment of the need to consider fluid as a primary end point in ERPs and to focus on leveraging a dynamic fluid assessment to guide perioperative fluid administration, not only in the operati ng room but postoperatively on the floor. “Hopefully, this will increase awareness about variability in practice, how that variability can impact perioperative outcomes, and ultimately how it can impact value delivery in the perioperative space,” he said.

Dr. Hopkins said we are living in a time where the definition of value, as it applies to perioperative medicine, is changing very rapidly. “In these times of rapid change, ERPs have surfaced as a way to improve the value of care by improving patient outcomes and reducing the cost required to achieve those outcomes,” he said.