Study ties common viruses such as flu to Alzheimer’s and other conditions — but the analysis has limitations, researchers warn

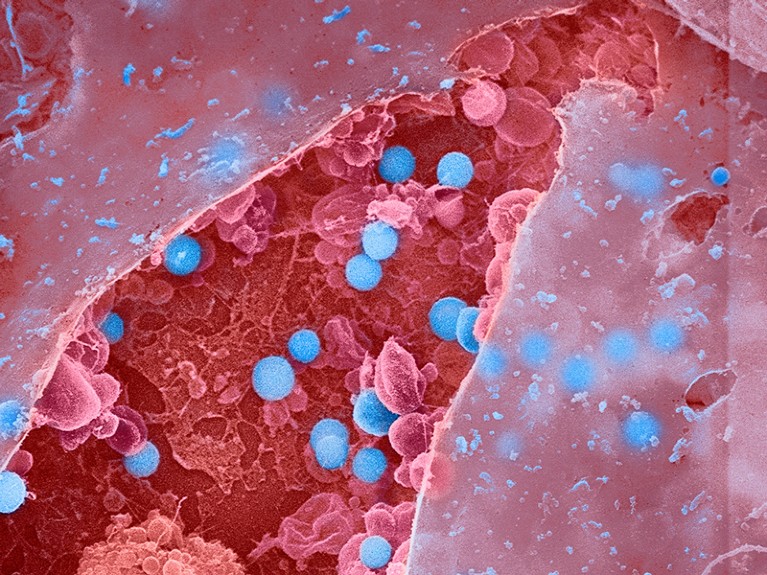

An analysis of about 450,000 electronic health records has found a link between infections with influenza and other common viruses and an elevated risk of having a neurodegenerative condition such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease later in life. But researchers caution that the data show only a possible connection, and that it’s still unclear how or whether the infections trigger disease onset.

The analysis, published in Neuron on 19 January1, found at least 22 links between viral infections and neurodegenerative diseases. Some of the viral exposures were associated with an increased risk of brain disease up to 15 years after infection.

“It’s startling how widespread these associations seem to be, both for the number of viruses and number of neurodegenerative diseases involved,” says Matthew Miller, a viral immunologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Mining health records

This isn’t the first time viruses have been linked to neurodegenerative disease. Infection with a type of herpes virus has been associated with the development of Alzheimer’s2, for instance. And a landmark study published in Science3 last year found the strongest evidence yet that Epstein–Barr virus is tied to multiple sclerosis. But many of these past studies examined only a single virus and a specific brain disease.The quest to prevent MS — and understand other post-viral diseases

To understand whether viruses are linked to brain diseases more broadly, Kristin Levine, a biomedical data scientist at the US National Institutes of Health’s Center for Alzheimer’s Related Dementias in Bethesda, Maryland, and her colleagues analysed hundreds of thousands of medical records to look for instances in which a person had both a viral infection and a brain disease on file.

First, the team examined records from about 35,000 people with brain diseases and about 310,000 people without, sourced from FinnGen, a large Finnish database that includes health information. The team found 45 significant links between infections and brain diseases, and then tested those against more than 100,000 records from another database, the UK Biobank. After this analysis, they were left with 22 significant pairings.

One of the strongest associations was between viral encephalitis, a rare inflammation of the brain that can be caused by multiple types of virus, and Alzheimer’s. People with encephalitis were about 31 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s later in life than were people who did not have encephalitis. Most other associations were more modest: people who had a bout of flu that led to pneumonia were four times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than were people who didn’t develop the flu with pneumonia. There were no pairings that suggested a protective link between viral infection and brain disease.

“I’m very excited they’re expanding this research broader than what other studies have looked at,” says Kristen Funk, a neuroimmunologist at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, who studies the link between herpesviruses and Alzheimer’s.

Data shortcomings

Kjetil Bjornevik, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and an author of the Epstein–Barr paper in Science, applauds Levine and her colleagues for bringing more attention to the role of viral infections in brain diseases. But he warns that their approach of using medical records “could be problematic” because they analysed only infections that were severe enough to warrant a trip to a health practitioner. Taking milder infections into account might weaken the associations, he says.Are infections seeding some cases of Alzheimer’s disease?

The data are also sourced almost exclusively from people of European ancestry, which means that the findings might not be applicable to the larger global population, Funk says. Furthermore, she adds, outside Europe, “certain viruses are more prevalent”, such as Zika or West Nile virus, so the analysis might have missed links between those pathogens and brain disease. Levine acknowledges the limitations of the analysis; the team worked with the data that were available, she says.

These limitations also underscore the difficulty of untangling whether a viral infection leads to neurodegenerative disease, or whether the disease makes a person more susceptible to infection, Bjornevik says. To make it even more tricky, the authors found that the more time that elapsed between the infection and the diagnosis of brain disease, the weaker the link was. The body is known to begin changing years before symptoms of brain disease develop and a diagnosis is made4, so it’s tough to determine which is causing which, he adds. Another plausible theory is that these viral infections might be accelerating molecular changes in the body that were already ongoing, says Cornelia van Duijn, a genetic epidemiologist at the University of Oxford, UK.Could long COVID be linked to herpes viruses? Early data offer a hint

If future studies add more weight to the connection between viral infection and brain disease, it could offer health officials a tangible way to delay the onset of neurodegenerative disease. Vaccines exist for many of these viruses, van Dujin says. Because multiple types of dementia are diagnosed late in life — close to the average life expectancy — if clinicians could postpone disease onset by even a couple of years, that could mean that many people might never develop the disease, she adds.

“It’s not very clear that the infections are causing brain disease,” she says. But viral infections aren’t pleasant, and if there’s any link to brain disease, “I think we owe it to people to prevent them.”