Turkey and Syria’s buildings have always been vulnerable to earthquakes, but war has made things worse.

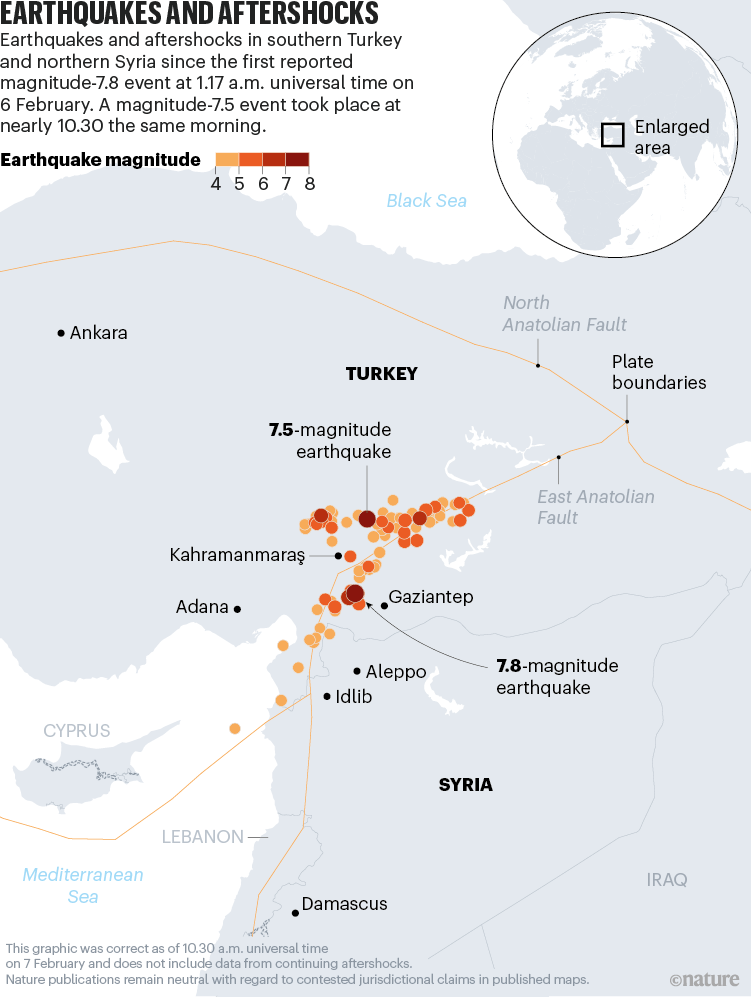

A magnitude-7.8 earthquake hit southeastern Turkey and parts of Syria in the early hours of the morning of 6 February. At least 17,000 people are known to have lost their lives, with thousands more injured. The quake was followed by a magnitude-7.5 event some 9 hours later, as well as more than 200 aftershocks.

The earthquake and its aftershocks have flattened buildings and sent rescuers digging through concrete debris to find survivors, with the death toll expected to increase further. Nature spoke to four researchers about the seismic activity in the region and what the next few days will bring.

Turkey is in an active earthquake zone

Most of Turkey sits on the Anatolian plate between two major faults: the North Anatolian Fault and the East Anatolian Fault. The tectonic plate that carries Arabia, including Syria, is moving northwards and colliding with the southern rim of Eurasia, which is squeezing Turkey out towards the west, says David Rothery, a geoscientist at the Open University in Milton Keynes, UK. “Turkey is moving west about 2 centimetres per year along the East Anatolian Fault,” he adds. “Half the length of this fault is lit up now with earthquakes.”

Seyhun Puskulcu, a seismologist and coordinator of the Turkish Earthquake Foundation, based in Istanbul, says people in Turkey are well aware of their vulnerability to earthquakes. “This wasn’t a surprise,” says Puskulcu, who last week was touring the cities of Adana, Tarsus and Mersin, and areas of western Turkey, delivering workshops on earthquake awareness.

The epicentre of the main earthquake was 26 kilometres east of the city of Nurdaği in Turkey’s Gaziantep province, at a depth of 17.9 kilometres. The magnitude-7.5 event occurred around 4 kilometres southeast of Ekinözü in the Kahramanmaraş province (see ‘Earthquakes and aftershocks’).

War has destabilized already-vulnerable buildings

Deaths in earthquakes are often caused by falling bricks and masonry. According to the US Geological Survey, many people in Turkey who were affected by the earthquake live in structures that are extremely likely to be damaged by shaking, with unreinforced brick masonry and low-rise concrete frames.

In a study1 published last March in Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Arzu Arslan Kelam at the Middle East Technical University, Ankara, and her colleagues suggested that the centre of the city of Gaziantep would experience medium-to-severe damage from a magnitude-6.5 earthquake. This is because most existing buildings are low-rise brick structures that are constructed very close to each other.

In 1999, a magnitude-7.4 earthquake hit 11 kilometres southeast of Izmit, Turkey, killing more than 17,000 people and leaving more than 250,000 homeless. After this tragedy, the Turkish government introduced new building codes and a compulsory earthquake insurance system. However, many of the buildings affected by this week’s quake were built before 2000, says Mustafa Erdik, a civil engineer at Boğaziçi University, Turkey.

Things are worse in Syria, where more than 11 years of conflict have made building standards impossible to enforce. The earthquake struck Syria’s northwestern regions, with buildings collapsing in Aleppo and Idlib. Some war-damaged buildings in Syria have been rebuilt using low-quality materials or “whatever materials are available”, says Rothery. “They might have fallen down more readily than things that were built at somewhat greater expense. We’ve yet to find out,” he adds.

What’s next?

Researchers say people need to brace themselves for yet more quakes and aftershocks, as well as deteriorating weather. “The possibility for major aftershocks causing even more damage will continue for weeks and months,” says Ilan Kelman, who studies disasters and health at University College London.

“The weather forecast for the region for tonight is dropping below freezing. That means that people who are trapped in the rubble, who might be rescued, could well freeze to death. So these hazards continue,” he adds.