Tummy Trouble

1/16

Everyone’s stomach gets a bit out of sorts from time to time. But in some cases, depending on your symptoms, you may need to see your doctor.

Gastritis

2/16

The liquid that helps you digest food has a lot of acid in it. Sometimes these digestive juices get through the protective barrier in your stomach and irritate its lining — that’s called gastritis. It can be brought on by bacteria, regular use of pain relievers like ibuprofen, too much alcohol, or stress. You can sometimes treat it with over-the-counter antacid or prescription medicines. But see your doctor because it can lead to bleeding or stomach ulcers.

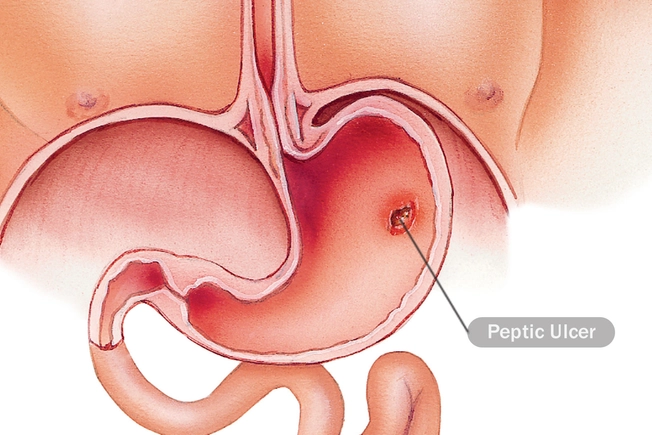

Peptic Ulcer

3/16

These are open sores on the lining of your stomach or the upper part of your small intestine. The most common cause is bacteria, but again, long-term use of aspirin, ibuprofen, and other painkillers can play a role. And people who smoke or drink get these ulcers more often. They’re usually treated with prescription medicines that decrease stomach acid or antibiotics, depending on the cause.

Stomach Virus

4/16

Also known as the stomach flu, this is a viral infection in your intestines. You may have watery diarrhea, cramps, or nausea, and you might throw up. You can get it from someone who has it or contaminated food. There’s no treatment, but it usually goes away on its own. See a doctor if you have a fever, you’re throwing up, dehydrated, or you see blood in your vomit or stool.

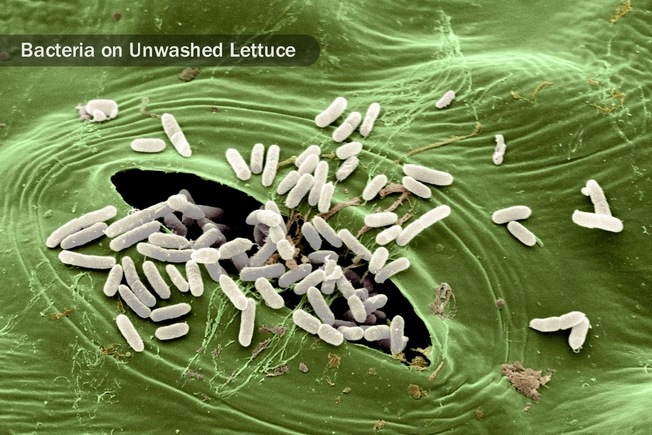

Food Poisoning

5/16

Bacteria, viruses, and parasites in food cause this illness. You may have diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. It happens when food isn’t handled properly. It usually gets better on its own, but see a doctor if you’re dehydrated, see blood in your vomit or stool, or you have diarrhea that is severe or lasts for more than 3 days. Also call your doctor if you have any symptoms of food poisoning and you have other health problems or have a weak immune system.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

6/16

This common illness affects your large intestine (also called the colon). It can cause cramping, bloating, and mucus in your stool. You may go back and forth between diarrhea and constipation. It’s not clear why it happens, but food, stress, hormones, and infection may all play a part. A doctor may be able to help you control symptoms through changes in your diet or lifestyle, or medication.

Lactose Intolerance

7/16

Lactose is the sugar in milk and other dairy products. If you don’t have enough of an enzyme called lactase, your body can have trouble breaking it down. That can cause diarrhea, gas, bloating, and belly ache. There’s no cure, but you can manage it if you have only a small amount of dairy in your daily diet, buy lactose-free dairy products, or take over-the-counter lactaid pills.

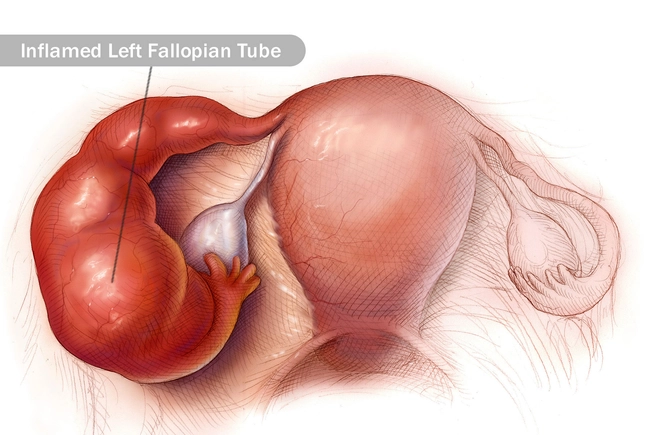

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

8/16

This happens to women: It’s inflammation of the reproductive organs, often following a sexually transmitted disease like chlamydia or gonorrhea. Besides pain in your belly, you might also have a fever, unusual discharge, and pain or bleeding when you have sex. If you catch it early, it can be cured, usually with antibiotics. But if you wait too long, it can damage your reproductive system.

Food Allergy

9/16

This happens when your body mistakes a certain food for something harmful and tries to defend against it. In addition to a stomachache, symptoms also can include tingling and swelling in your mouth and throat. In severe cases, it can cause shock and even death if it’s not immediately treated with a drug called epinephrine. Shellfish, nuts, fish, eggs, peanuts, and milk are some of the more likely triggers.

Appendicitis

10/16

Your appendix is a finger-shaped organ that is found at the beginning of your colon in the lower right part of your belly. It’s not clear what the appendix does, but when it’s inflamed, it’s usually infected and should be taken out. If it bursts, it can spread bacteria. Pain often starts at your belly button and spreads down and to the right. See a doctor immediately if you think you might have appendicitis.

Gallbladder Attack

11/16

This happens when gallstones — small rocks made from juices that help with digestion — block the tubes, or ducts, that run between your liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and small intestine. The most common symptom is abdominal pain — if it is severe or lasts more than several hours, call your doctor. You may also have nausea, vomiting, fever, tea-colored urine, and light-colored stools. The stones often move on their own, but you might need surgery if they don’t.

Incarcerated Hernia

12/16

A hernia happens when a part of your intestines slides through your abdominal wall. When it gets twisted or moved, and cut off from its blood supply, it can cause severe pain in your belly. Surgery is often needed quickly to correct the problem.

Constipation

13/16

Exercise, plenty of water, and foods that have a lot of fiber, like prunes and whole grains, can help. But if you regularly pass fewer than three stools a week, have to strain to go, and your stools are usually lumpy and hard, that can be a sign of a more serious condition. See your doctor if you have any of these.

Pancreatitis

14/16

This happens when your pancreas, an organ that helps your body process sugar and digest food, gets inflamed. You may have pain in your upper belly that gets worse after you eat. You may also have nausea, and you might throw up. Mild cases may go away on their own, but severe cases can be dangerous. Your doctor may ask you to stop eating for a day or two and give you pain meds. If that doesn’t clear it up, you might need to be in the hospital to get nutrition and fluids.

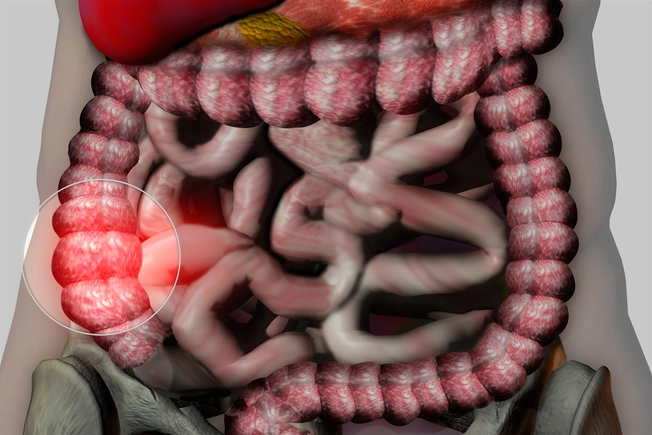

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

15/16

Inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, has two main forms: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. In both conditions, your immune system seems to overreact and inflame your intestinal tract. Though IBD doesn’t affect your stomach directly, belly pain and nausea are common symptoms, along with diarrhea, joint pain, fever, skin rashes, and other symptoms. Your doctor can help you manage your IBD with special medications along with lifestyle changes.

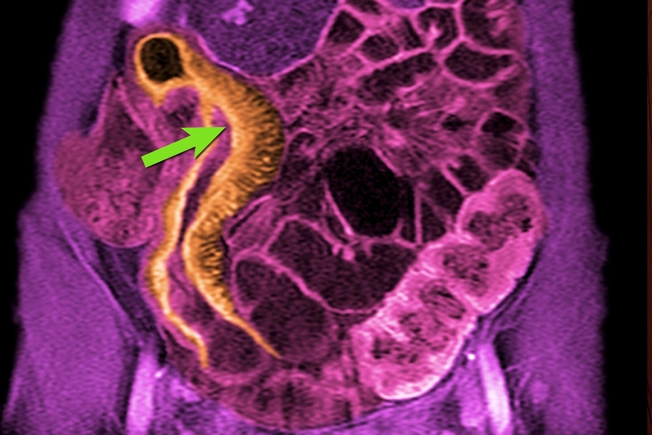

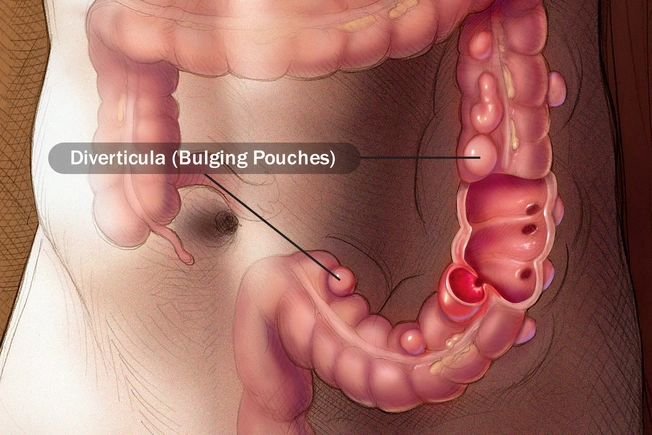

Diverticulitis

16/16

Small bulging pouches can form in the lining of your digestive system, usually in the lower part of your large intestine. They’re pretty common and don’t typically cause problems. But if they get inflamed or infected they can cause severe abdominal pain, nausea, and changes in bowel movements. Rest and changes in your diet can help. Your doctor might prescribe antibiotics as well.