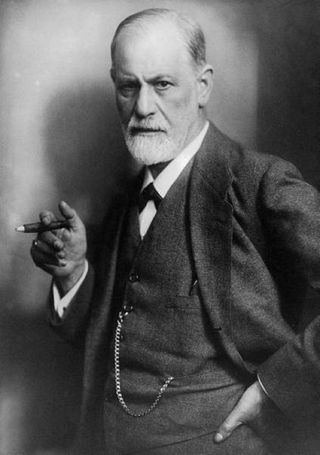

Sigmund Freud postulated that for psychoanalysis to be effective, the client must share with the analyst all that crosses their mind during the course of the clinical hour. Whether their thoughts are deemed by them to be relevant and consequential or completely tangential and random, that the analyst needed access to that information to successfully understand the rest of the material presented in the session. This of course included feelings and thoughts about the analyst as a means of comprehending transferential issues at hand. Most contemporary analytic theories continue to support the importance of the client sharing associative thoughts, if perhaps with a bit less dogmatic demand.

One way to consider the relevance of this postulation, referred to as Freud’s fundamental rule, is to compare it to the associative details of a dream. Sometimes clients want to provide only the highlights of a dream; the story.

Client: “I had a dream last night where I was on this boat, but couldn’t stand to get to the sail. It was flapping in the wind making the ride so bumpy. The motion of the boat was making me so sick I just wanted to jump overboard. I literally still feel dizzy now.”

Therapist: “Tell me more about the dream. Start from the beginning.”

Client: “Oh no, it isn’t important, I was just thinking about it because I felt a bit dizzy when I sat down.”

Therapist: “Let’s imagine for a minute that it might be relevant to something you want us to think about today. Tell me about it.”

Client proceeds to report dream, with details, along with associations about details based on therapist probing. As the dream unfolds, some of the specifics (the boat’s cooler type) point to a particular sailing trip he took with his father in the year after his mother died, where he felt particularly shamed by his father about his distraction and inattention. Nausea was and continues to be a common response to feelings of shame for this client.

The random detail of the cooler was able to bring his father to mind, and man who did a very poor job of helping his son deal with the death of his mother. While the client had never been close with his father, he needed him desperately once his mother had died and did everything he could to align himself with the dad and try to please him. Above all things, he avoided making his father angry. The thing that made his father the most angry was when his son was angry or challenged him in any way. The result was that the son worked hard to swallow his anger, which my client instead experienced as nausea. When his father would shame him, which he did routinely, instead of feeling angry which could threaten his much needed relationship with the father, he felt both nauseous, and suicidal.

Suicidality in the face of a recent loss to death is not just the wish to be dead, but the wish to join the person who has recently died. In dream analysis, bodies of water are frequently associated with the mother, her womb and/or her body. Hence his wish to manage his nausea in the dream, by jumping into the water, is his desire to escape his father, and return to his mother, in the womb or in death.

Most folks have heard of the term “free association.” It is both a technique, and more broadly, a concept. The technique is a therapist offering up a list of words that a client responds to with the first word that comes into their head. But more broadly, it is the meat and potatoes of every session. A skilled analytically oriented therapist is listening all the time for links and associations between topics, feelings, thoughts, gestures in both the client and themselves.

Upon entering a session, clients frequently make statements they want to view as simply conversational and separate from their clinical content. They mention the congested traffic; unaware they are commenting on their internal state. They ask if their therapist changed something in the office; alerting us to their anxiety that we might be different than they expect us to be. They tell us they need to eat their sandwich, communicating emotional hunger they fear will be left dissatisfied.

I know, I know, many of you will refute these statements are meaningful revelations about the internal state of the clients’ world. And alone, I would never interpret them, either to myself or to the client, just as I would never assume a body of water in a dream is the mother or her body. These little clues, associations, messages from the unconscious, are meant to be noted, and then watched in the course of the session. If relevant, they will join with other fragments of the session to reveal a picture, a story, a connection of truths, for our work as clinicians is to develop the skills necessary to note and pull together the fragments of unconscious communication so we may offer them to our client for their examination.

Another example.

The client is telling us about a conversation they had with their ex. There is a long silence in the session.

Therapist: Can you say what is happening for you right now?

Client: Nothing. I just got distracted.

Therapist: Tell me what you were thinking about.

Client: Ugh, it is too embarrassing. I was just making a list some stuff I need to get from the store on the way home.

Therapist: And what is on the list?

Client: Hahaha. Some shampoo, dishwashing liquid, and carpet cleaner.

Now a client who has been in therapy for a while with a clinician who desires access to unconscious materiel would have known to offer up the list making distraction without probing. If we can imagine that whatever we are discussing, the conscious mind has primary control of the conversation. If we are discussing the kind of topics we typically explore in therapy, the unconscious mind is just as present. The only way the unconscious mind can take control of the conversation is by forcing us to fall asleep and thereby dream. Otherwise it must insert itself. A primary it inserts itself is through “distracting” thoughts. Remember, the unconscious speaks through symbols.

So, our client who was talking about her ex has lots of mixed feelings about her ex. She has been struggling to understand why she continues to be so preoccupied with him. Her conscious mind doesn’t get why she isn’t ready to let him go. Perfect reason to keep an ear out for what the unconscious mind might be able to tell us about why she is stuck in her process.

The other detail that the unconscious offered up is that all the items she listed were cleaning supplies. Now certainly one could argue, as clients often do, that she had that list in her head long before the session, the list likely has many more items, that were not readily available to her mind, because this particular thought surfaced for a reason, and offered up the items on her list that might us help discern her internal state. Again, based on clinical experience with this client and the topic of her ex, the therapist speculated with the client if the conversation about her ex was making her feel dirty, or somehow unclean. The client burst into tears. Over the remaining hour, and many proceeding sessions, the client was able to talk about having felt pressured to engage in sexual activities outside her interests and comfort zone with her ex that left her feeling humiliated for “dirtying herself” (her language) for someone who “still” left her.

The unconscious mind routinely attempts to insert itself into our conscious thought throughout our day, in the form of Freudian Slips, where we mean to say one thing but accidentally say something else, through song lyrics that get stuck in our heads, day dreams, or remembering something important in the middle of a conversation about something else. Unless we are someone who actively attended to unconscious communication, most of these clues to the burdens of our soul go unattended.

The unconscious, savvy as it is, understand that a therapy session, with an unconscious focused therapist, is a worthy place to try to get seen. From thoughts on the way to therapy, opening statements upon entering the session, “casual” questions to the therapist, “different” topics brought into the same session, “random” comments made about a beverage in the session, a purse zipper, seeing a possible bug out of the corner of their eye… everything! In the short span of 50 minutes, the unconscious is making its efforts to be seen, by the client, and by us.

A third example

During the prior week there is a scheduling mistake that is the fault of the therapist. It makes for a significant inconvenience for the client, including being unable to attend a session that week. At the start of the session there is an effort on the therapist’s part to discuss the incident. The client insists it is unproblematic and “no big deal.” This following is the next topic the client brings to the session.

Client: I went to see my Doctor last week. He is such an idiot. He can’t even remember what he was treating me for. I wanted to be like “Didn’t you pay attention in school?”

Hear the rage and hostility. The client doesn’t know it is about us. They were sincere when they said it was “no big deal.” We likely don’t want to know it is about us either. We might even try to sympathize with them, or try to help them figure out if they are getting the right medical help.

We would have to be bold, and have enough of a relationship established with the client, but the right clinical move is to help the client know that we are the “Doctor” they are talking about (even if we don’t have a Doctorate). Even though they rejected our suggestion earlier that they might be angry, we have some “evidence” now and can help them see the parallels through the details of the story they just reported to the incident with us.

Anytime a client is talking about medical professionals, professors, or other authority figures, we should be listening for transferential themes.

Conclusion

If clients just need to think through something with someone, they don’t need a therapist. They can take a long walk, or talk to a friend or counselor (as opposed to a psychotherapist), meditate, or journal. Knowing one’s conscious mind is hard, but not what you pay a therapist big bucks for. What we can offer clients is access to a whole other part of them that is struggling right along with them, with every single one of their meaningful issues. Just as they spend their days trying to unravel their thoughts and feelings about complex emotional issues, their unconscious is trying to do the same thing.

The reason some of us are estranged from our unconscious, is it speaks in coded, symbolic language. It is by design veiled to protect us from information and truths that may be difficult to handle. But in its effort to be engaged, heard, appeased, attended to, it will sabotage, misdirect, and resist our conscious efforts until it is assured its needs be meet.

Clients often come to us with issues they believe defy reason. They insist that their behaviors and feelings make no sense and that they simply don’t understand why they keep doing the same thing. There is a good answer. And their unconscious holds the clues.

Smith is the founder/director of Full Living: A Psychotherapy Practice, which offers clinical services with seasoned, cultural competent clinicians throughout Philadelphia and the surrounding areas.

Source:www.psychologytoday.com