New regulations for drilling into the seabed could come any day now, following two years of infighting between an international regulatory body, drilling companies, and scientists.

The deep ocean is a mysterious, pitch-black world populated by creatures specially adapted to the crushing pressure, the dark, and the near-freezing temperatures. Though the ocean covers 70 percent of Earth’s surface, less than one percent of the deep ocean—about 200 meters deep, where light begins to dwindle—has been mapped. Frequently, when scientists explore there, they discover species we never even knew existed. But they also have discovered that this ecosystem is full of metals like manganese, nickel, cobalt, and lithium that humans use in everything from phones and electric cars to wind turbines.

Private companies and a number of countries are eager to mine these metals, though the process is generally very destructive to ecosystems. After scientists simply raked the seabed in a 1972 experiment to test the environmental impacts, the area they tested never recovered.

Yet, companies may soon get the green light to conduct deep-sea mining anyway.

The Fox in the Henhouse

Gerard Barron, chairman and CEO of The Metals Company, holds a nodule brought up from the seafloor, which he plans for his company to mine in the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, June 2021.

The Kingston, Jamaica-based International Seabed Authority (ISA), an autonomous organization under the auspices of the United Nations, is in charge of that decision. Created in 1994, the ISA is charged with protecting the marine environment in international waters “for all mankind.” It governs about 54 percent of the ocean—the ocean that is essential to planetary health, because it generates 50 percent of the oxygen we use, absorbs 25 percent of carbon dioxide emissions, and captures 90 percent of excess heat humans create. The ISA is also in charge of issuing contracts to extract resources from international waters, and creating regulations for such extraction, which many conservationists liken to putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. It’s further charged with guarding the rights of developing nations, so that if resources are extracted, wealthy nations do not unfairly benefit from what is considered a common human heritage.

Some have accused Michael Lodge, the secretary general in charge of the ISA, of being overzealous when it comes to mining. A 2022 New York Times investigation included documents showing that since 2007, the ISA has been sharing key information with a Canadian mining company, now known as The Metals Company; it also set aside the most promising tracts for that company, including the mineral-rich Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific. This prompted some agency employees to quit in protest. While the ISA’s role was to protect developing nations, The Metals Company, which anticipates garnering $85 billion from the area, plans to pay only 10 percent to the developing countries sponsoring it

That New York Times investigation was not the only article about Lodge’s apparent advocacy for mining. There have been others in publications including The Los Angeles Times and The Guardian. And a recent New York Times story reports that diplomats from ISA member nations called Lodge out for clashing with council members who wanted to slow the implementation of mining.

The ISA is governed by a 36-member rotating council that represents 169 member states, including 167 countries and the European Union. Some of these members say Lodge has stepped outside his administrative role in pushing for deep-sea mining. Popular Mechanics was unable to reach Lodge for comment.

Gerard Barron, chairman and CEO of The Metals Company, hopes that his company will be able to mine the seafloor for nickel, cobalt, and manganese in the Pacific Ocean.

Some council members—including Russia, China, South Korea, India, Britain, Poland, and Brazil—have applied and been approved for contracts to explore deep-sea mining; the ISA does not yet have authority to issue contracts to exploit the resources. (Brazil, for its part, just called for a ten-year moratorium on deep-sea mining.) But several other countries—including France, Germany, Spain, New Zealand, and Costa Rica—want a moratorium on deep-sea mining until its impacts are better understood. They are joined by the United Nations Environment Program, the World Bank, and nearly 800 scientists. Meanwhile, several companies, including Google, Volvo, and Samsung, have signed a pledge not to use materials extracted from the deep sea until it is “clearly demonstrated that such activities can be managed in a way that ensures the effective protection of the marine environment.”

Thanks to a rule written into the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a set of regulations for deep-sea mining may be forced into place before the science is clear. This rule states that if a government expresses an interest in mining in international waters, the ISA has 24 months to create a regulatory framework for that activity. In 2021, one of The Metals Company’s sponsors, plus a member of the ISA’s council, the Pacific nation of Nauru, triggered that rule. July marks 24 months.

The Deep Sea: Mining Resource or Crucial Ecosystem?

These black polymetallic sea nodules—nickel, manganese, and cobalt-rich mineral deposits—are balls that form naturally deep under the sea.

Proponents of deep-sea mining, such as mining companies and countries interested in cashing in on rare-earth and other minerals, contend that the transition to renewables is absolutely dependent on these minerals. Rare-earth metals are used in electric car batteries, cell phones, and wind farms, and are considered essential in transitioning from fossil-fuel vehicles to electric ones. Failing to mine these metals, they say, will lead to shortages and slow the renewable transition.

They argue that tons of these metals can simply be sucked up from the abyssal plains, like the CCZ, where they now lie in the form of polymetallic nodules, which look like loose rocks resting on the bottom of the ocean. According to the United States Geological Survey, a conservative estimate of polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone manganese nodule field, the largest globally, is 21.1 billion dry tons—that is more than the known tonnage of many critical metals in reserves on land.

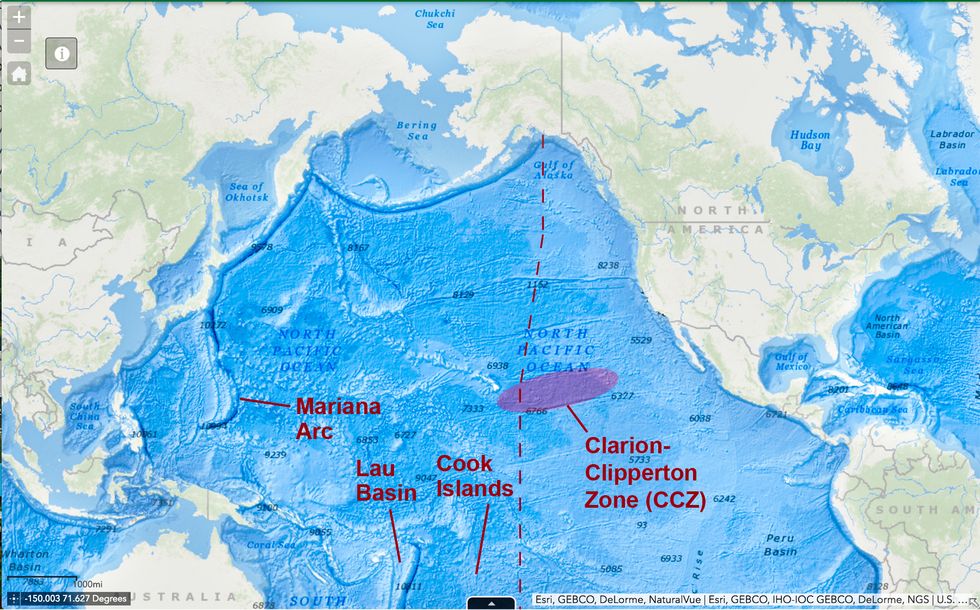

Pacific Ocean, showing locations of Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), the Mariana Arc, Lau Basin, and the Cook Islands.

Other metals that are expected to be mined are in cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts and near thermal vents. About 7.5 billion dry tons of cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts are estimated in the Pacific Ocean Prime Crust Zone. Theoretically, this could stem some of the human rights abuses commonly associated with cobalt mining.

Gerrard Barron, CEO of The Metals Company, suggests that deep-sea mining will allow terrestrial mining to diminish.

“There needs to be an acceptance of the fact that we need more metals,” he tells Reuters. “Why does it make sense to destroy rainforests to mine nickel, but not extract the metal from the bottom of the ocean at a part of the planet with the least life on it?”

In a single expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in May 2023, more than 5,000 new species were discovered.

Catherine Weller, director of global policy for Fauna & Flora International, tells Popular Mechanics that Barron’s argument is fallacious. (The organization, founded in 1903, lists Sir David Attenborough as a vice president.) It published a widely circulated report in 2020 about the environmental damage of deep-sea mining. There’s no reason to believe that terrestrial mining will stop or even slow just because deep-sea mining commences, Weller says. And as for no life being where the mining is intended to occur, Fauna & Flora’s marine director, Sophie Benbow, says that’s far from true; the deep sea is thriving with biodiversity. In a single expedition to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in May 2023, more than 5,000 new species were discovered, and most of them were endemic to the region and not found anywhere else on the planet.

The metallic nodules on the abyssal plains that miners want to hoover up form over millions of years in a remote part of the planet where fine sediment filters down at a rate of about a centimeter every millennium. It is home to untold thousands of species.

A Psychropotes longicauda sea cucumber is seen as it is transferred into an ethanol-filled specimen jar for scientific preservation, in a laboratory within the Natural History Museum on May 24, 2023 in London, England. Collected from the seabed using a remotely-operated system, researchers have managed to collect thousands of samples of deep-sea anthropods, many of which are being seen for the first time. A new study has highlighted the extent of biodiversity in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, the world’s largest mineral exploration region. The research has found that over 90 percent of species in one of the most likely future mining sites are currently undescribed by science, and are threatened by deep-sea mining, due to a global surge in demand for metals such as cobalt and nickel.

The ferromanganese crusts host corals, sponges, tuna, sharks, dolphins, and sea turtles. Hydrothermal vents, where ore is also found, are superheated liquid rising to the water column from closer to Earth’s core. They give us clues to the origins of life and harbor their own unique and rare ecosystem that functions largely without photosynthesis.

“Mining in those areas, we would wipe out huge numbers of species,” Benbow says, many of which are “quite funky.” “They’re so uniquely adapted to living in near freezing temperatures, almost complete darkness, massive pressures. And there are some pretty cool creatures.” She lists the Dumbo octopus, species of snailfish with holes in their skulls to deal with the pressure, and the sea pangolin. “The species in the deep, they are unique and beautiful in their own right … each of them have their own role in that ecosystem.

Studying these species, their adaptation strategies, and their ecosystem could also lead to discoveries in areas such as medicine and technology, Weller argues. Conversely, mining in the area is widely believed to mean the complete and irreversible destruction of the ecosystem with far-reaching consequences. Disturbing an ecosystem that has been protected on the seafloor for millennia, Benbow notes, could also exacerbate climate change.

“At the bottom of the sea, there are sediments [that] have been found to be one of the most expansive and critical carbon reservoirs on the planet,” she says. Deep-sea mining would disrupt those sediments, even if a company were just “vacuuming” nodules off the seafloor. Plus, any impacts in the ocean would enter the water column and possibly damage very large areas up to kilometers away.

Is Deep-Sea Mining Worth It?

The sun sets on the mining vessel Hidden Gem after a demonstration against deep-sea mining, February 8, 2022, the Netherlands.

There is also a question about whether deep-sea mining would, in fact, solve the problems it promises to solve. An article in Nautilus quoted investor and deep-sea explorer Victor Vescovo as noting that the deep sea is an extremely hostile environment to those not designed to live there, and certainly to machinery. Between the incredible pressure of the deep sea, the salt water, the cold, and the darkness, machinery operating there must be incredibly resilient. He argues that the investment needed to mine this inhospitable area would not justify the cost.

Moreover, the permanent batteries constructed from such minerals—while hailed as a solution to the CO2 problem—have created their own problem. One study showed that, between 2010 and 2020, the use of permanent magnets cumulatively resulted in 32 billion tons CO2-equivalent of greenhouse gas emissions globally. (This is a calculation comparing it with greenhouse gas emissions.)

And Fauna & Flora’s Weller notes that emerging technologies may soon make rare-earth mining unnecessary. Experiments are underway to replace the rare-earth metals we currently use with materials that can be created in a lab. And more and more countries are turning to recycling rare-earth materials. Plus, some of the assumptions that are intended to justify deep-sea mining, such as the argument that the renewable transition requires replacing all fossil fueled cars with electric ones, negates other, possibly better solutions. This includes increasing public transit and reducing the number of cars on the road, since most of them spend 90 percent of their time parked, anyway.

Andrew K. Sweetman, professor and research leader at the Lyell Centre for Earth, Marine Science, and Technology at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Scotland, holds a deep-water fish, called a Rattail, brought up as part of the research to see the effects mining will have on the environment in the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, June 2021.

Though the ISA was scheduled to start taking applications for deep-sea mining in July, many of its council members believe such decisions are premature. Conservationists hope the ISA will find a different solution to help the renewable transition.

“I think it would be pretty ridiculous,” Weller says, “to be in the process of solving one crisis by creating another huge crisis.”