For the first time, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved oral devices that treat severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). These devices offer an alternative to more common sleep apnea treatments, like continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy and surgery.

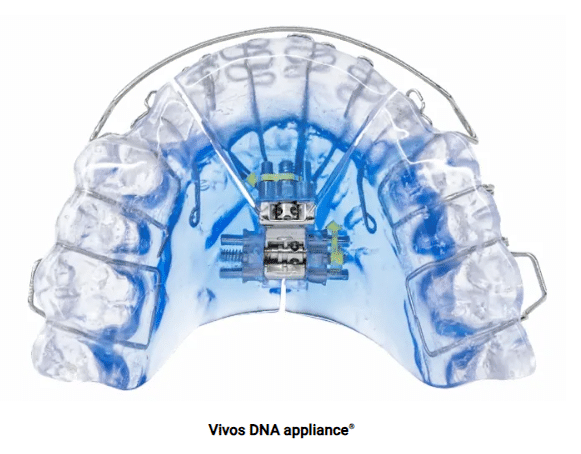

Vivos Therapeutics, Inc. manufactures the oral devices, called Complete Airway Repositioning and/or Expansion (CARE) appliances. They are dental appliances that look similar to retainers. Trusted Source National Library of Medicine, Biotech Information The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health by providing access to biomedical and genomic information. View Source Some appliances are worn only during sleep, while others are worn day and night.

With FDA clearance, the manufacturer can market CARE appliances in the U.S. The approval is significant because it may allow more people with sleep apnea who can’t use CPAP therapy or get surgery to receive treatment. Without treatment, a person with sleep apnea faces a higher risk of severe health problems.

Data the company submitted to the FDA on 73 people with severe OSA treated with CARE appliances show that about 80% experienced at least some improvement in sleep apnea symptoms. Another study by a team of researchers that included some members of the medical advisory board for Vivos Therapeutics, found that about 64% of participants had less severe OSA following treatment with a CARE appliance. About 26% recovered from OSA completely.

Although approved by the FDA, CARE appliances may only be appropriate for some with OSA. A dentist must evaluate patients and custom-fit CARE appliances to each individual’s teeth and mouth. And people should check with their insurance company about covering the costs.

An advantage of the CARE appliances is that, unlike CPAP therapy, they may not have to be used for a person’s lifetime. Instead, they are worn daily for at least six months and, at most, a year and a half. After that, the benefits should remain for many people without any further need for the devices.

Some people develop OSA because they have naturally narrow mouths and throats. Muscles in their upper airway relax while they’re asleep, narrowing or blocking their airway and causing repeated pauses in breathing during the night. Trusted Source National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) The NHLBI is the nation’s leader in the prevention and treatment of heart, lung, blood and sleep disorders. View Source CARE appliances used to treat OSA gradually expand the roof of a person’s mouth, called the palate, by pushing their teeth outward. Dentists must periodically adjust the appliances to keep expanding the palate. Some CARE appliances also move the lower jaw forward. Both of these changes help create space in the airway, making it less likely to become blocked during sleep.

Up to 83% of people with sleep apnea who are prescribed CPAP therapy do not use it as often as directed. Also, surgery can be expensive, risky, and potentially less effective than other treatments. For these reasons, CARE appliances may become an attractive treatment option.

Studies of CARE appliances suggest they are not likely to cause major side effects. In some instances, they might create space between teeth.