The Smell-Taste Connection

1/12

When your sense of smell goes south, taste usually follows. That’s because the olfactory area in your nose controls both. When you chew food, odor molecules enter the back of your nose. Your taste buds tell you if a food is sweet, sour, bitter, or salty. Your nose figures out the specifics, like if that sweet taste is a grape or an apple. If you plug up your nose, food doesn’t taste the same because you can’t smell it.

Age

2/12

As you age, you lose some of the olfactory nerve fibers in your nose. You have fewer taste buds, and the ones you have left aren’t as sharp, especially over age 60. This often affects your ability to notice salty or sweet tastes first, but don’t add more salt or sugar to your food. That could cause other health issues.

Illness or Infection

3/12

Anything that irritates and inflames the inner lining of your nose and makes it feel stuffy, runny, itchy, or drippy can affect your senses of smell and taste. This includes the common cold, sinus infections, allergies, sneezing, congestion, the flu, and COVID-19. In most cases, your senses will return to normal when you feel better. If it’s been a couple of weeks, call your doctor.

Obstructions

4/12

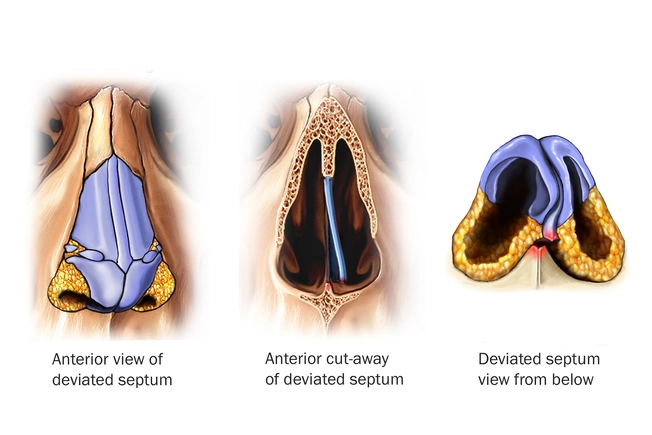

If you can’t get enough air through your nose, your sense of smell suffers. And smell affects taste. Blockages happen if you have nasal polyps. These are noncancerous tumors that grow in the lining of your nose and sinuses. Or you could have a deviated septum that makes one of your nasal passages smaller than the other. Both are treated with nasal sprays, medication, or surgery.

Head Injury

5/12

Your olfactory nerve carries scent information from your nose to your brain. Trauma to the head, neck, or brain can damage that nerve, as well as the lining of your nose, nasal passages, or the parts of your brain that process smell. You may notice it immediately or over time. In some cases, your senses return on their own, especially if the loss was mild to start. You may partly get better and only be able to taste or smell strong flavors and scents.

Certain Medical Conditions

6/12

Doctors don’t understand why, but loss of smell can be an early warning sign of dementia, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease. Other medical conditions can damage the nerves that lead to the smell center of your brain, too. These include diabetes, Bell’s palsy, Huntington’s disease, Kleinfelter syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Paget’s disease of bone, and Sjogren’s syndrome. If you can’t taste or smell after a few days, talk to your doctor to rule out other conditions.

Cancer and Treatment

7/12

Certain kinds of cancer and treatment can change the messages between your nose, mouth, and brain. This includes tumors in your head or neck and radiation to those areas. Chemotherapy or targeted therapy and some medications for side effects can also have an effect. You may have a metallic taste in your mouth or find that certain odors are different or stronger. These issues often go away when your treatment ends.

Medication

8/12

Some prescription and over-the-counter medications can shift your senses, especially antibiotics and blood pressure medications. They either alter your taste receptors, scramble the messages from your taste buds to your brain, or change your saliva. Talk to your doctor before you stop taking any medication.

Vitamin Deficiencies

9/12

Loss of taste and smell could be your body’s way of telling you you’re low in vitamins. Certain conditions and medications can cause you to be low in vitamins associated with smell and taste, like A, B6, B12, and zinc. It can be a chicken-egg situation, too: If you eat less because you can’t smell or taste anything, your body may not get vitamins it needs.

Smoking, Drugs, and Chemicals

10/12

Besides its ability to cause cancer, tobacco smoke can injure or kill the cells that help your brain classify smells and taste. Smoking can also cause your body to make more mucus and lessen your number of taste buds. Cocaine use can have a similar effect on your sensory cells. So can hazardous chemicals like chlorine, paint solvents, and formaldehyde.

Diagnosis

11/12

After a physical exam, your doctor will check your ability to taste and smell separately. For the smell test, you’ll name a series of scents in small capsules or on scratch-and-sniff labels. A taste test involves strips that you identify as sweet, sour, bitter, salty, or umami, also called savory. Your doctor may look inside your nose with an endoscope (a camera on the end of a flexible tube) or order a CT scan for a better view of your sinuses, nose nerves, and brain.

Complications

12/12

When you lose your senses of smell and taste, it affects your life in many ways. This condition is a safety risk since you can’t smell smoke, poison, or gas or taste spoiled food. Use fire alarms, check expiration dates on food, and switch to electric if you have natural gas. Always eat healthy food, even if you can’t taste it.