Presentation of Case

Dr. Alison C. Castle: A 70-year-old woman with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was evaluated in a clinic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, because of cough, shortness of breath, and malaise.

Fifteen years before the current presentation, the patient received a diagnosis of HIV infection after she had presented with substantial weight loss and fatigue. The initial CD4 cell count obtained at the time of diagnosis was 29 cells per microliter (reference range, 332 to 1642). Antiretroviral therapy (ART) with stavudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz was started. During the subsequent year, the symptoms resolved, the HIV RNA level became undetectable, and the patient reported adherence to her medications. Ten years before the current presentation, additional ART became accessible within South Africa, and the ART regimen was changed to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz.

Five years before the current presentation, the patient was admitted to a local hospital because of diarrhea and diffuse myalgias, and she was found to have virologic failure. The ART regimen was changed to zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir–ritonavir. During the subsequent 4 years, the patient reported adherence to these medications without a lapse in treatment. The HIV RNA level ranged from 68 to 594,000 copies per milliliter of plasma (reference value, undetectable).

Twelve months before the current presentation, the patient had new shortness of breath, cough, anorexia, and weight loss. During the subsequent 4 weeks, the symptoms progressively increased in severity. When the shortness of breath worsened to the extent that she was unable to walk, she sought evaluation at the clinic. The temporal temperature was 36.8°C, the blood pressure 104/64 mm Hg, and the pulse 87 beats per minute. The body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) was 16.9. On examination, the patient appeared ill but was able to speak in full sentences. Auscultation of the chest was limited because of frequent coughing; diffuse crackles were present in both lungs.Table 1. Laboratory Data.

Laboratory Data.

Nucleic acid testing of a nasopharyngeal swab was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Examination of an acid-fast bacilli smear of the sputum was positive for mycobacteria, and subsequent nucleic acid testing and culture of the sputum was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. In accordance with recommendations from the South African Department of Health, the patient was instructed to isolate at home and complete a course of treatment for tuberculosis, which included rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.

During the subsequent 6 months, the patient took the antimycobacterial medications, and the shortness of breath and cough decreased but still persisted. Her weight decreased by 8 kg, even though the anorexia had resolved. Four months before the current presentation, new headaches and mouth ulcers developed, and the patient sought evaluation at the clinic. A sputum specimen was obtained for examination of an acid-fast bacilli smear and mycobacterial nucleic acid testing and culture, all of which were negative. The HIV RNA level was 151,000 copies per milliliter of plasma. The patient was scheduled for a follow-up appointment.

Twelve days before the current presentation, the patient presented to the clinic for follow-up, and the ART regimen was changed to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, and dolutegravir. When the symptoms did not abate, the patient presented to the clinic for additional evaluation. She described persistent shortness of breath and dry cough, as well as headaches on the right side and mouth ulcers. The review of systems was notable for fatigue and weakness during the past 12 months, as well as fever, night sweats, chest pain, mouth ulcers, and odynophagia. She had no ageusia, anosmia, vision changes, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, or joint pain. Radiography of the chest had not been performed.

The patient had not received vaccines for coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). She took tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, and dolutegravir, as well as acetaminophen for muscle pain as needed. There were no known drug allergies. She did not smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, or use illicit drugs; she did not take any remedies from traditional healers. The patient lived with her daughter in a rural farming community in a coastal region of South Africa, and she had not traveled recently. She commuted by foot within her community and had regular exposure to cattle, goats, chickens, and dogs. Her household water supply originated from a borehole and was untreated.

On examination, the patient was alert but appeared ill and cachectic. She coughed throughout the interview. The blood pressure was 97/71 mm Hg, the pulse 91 beats per minute, and the respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. The body-mass index was 13.7. The mucous membranes were dry. She had thrush on the tongue, as well as superficial ulcers on the buccal mucosa. On auscultation of the chest, diffuse crackles were present in both lungs and were worst in the right lower lobe. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. The blood levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase were normal. Other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1.

A diagnostic test was performed.

Differential Diagnosis

Dr. Rajesh T. Gandhi: I am aware of the final diagnosis in this case. This 70-year-old South African woman, who had advanced HIV infection and a recent history of Covid-19 and pulmonary tuberculosis, presented with dyspnea, cough, odynophagia, and headaches. On examination, she had oral candidiasis, oral ulcers, and pulmonary crackles. Laboratory studies were notable for pancytopenia, a low CD4 cell count (<10 cells per microliter), and a decrease in the HIV RNA level after a recent viral rebound. Radiographs were not available.

When formulating a differential diagnosis, I will first define the features of her underlying condition, including her recent infections and immunocompromised state. Then, I will identify potential causes of her initial respiratory symptoms. Ultimately, I will refine the differential diagnosis on the basis of subsequent features of her presentation, including the oral ulcers and headaches.

DEFINING THE FEATURES OF THE PATIENT’S UNDERLYING CONDITION

At the time of the diagnosis of HIV infection, the patient had had a CD4 cell count of 29 cells per microliter — the diagnosis in this patient, as in many patients, was delayed until she already had a low CD4 cell count.1-3 A delayed diagnosis of HIV infection puts patients at risk for many opportunistic infections and cancers, puts sexual partners at risk for HIV acquisition, and is associated with a higher risk of subsequent complications, most likely because of a “legacy effect” of immune dysregulation.4 In addition to advanced HIV infection, the patient had a recent history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studies suggest that persons with HIV infection have worse Covid-19 outcomes, particularly if they have a low CD4 cell count or a high HIV RNA level.5-8 The patient’s markedly immunocompromised state placed her at risk for persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent fungal superinfection. Finally, she had a recent history of pulmonary tuberculosis, which also increases the risk of severe Covid-19 outcomes and fungal superinfection, perhaps because of lung damage.5

IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL CAUSES OF THE PATIENT’S INITIAL RESPIRATORY SYMPTOMS

In this patient with advanced HIV infection, potential causes of her initial respiratory symptoms include noninfectious complications, such as cancer and heart failure, as well as infectious causes of pneumonia.

Cancer

Advanced HIV infection is associated with several cancers, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and human herpesvirus 8–associated cancers, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s sarcoma can involve the lungs but is an unlikely diagnosis in this patient for two reasons. First, there were no evident mucocutaneous lesions, unless the oral ulcers were sarcomatous lesions. Second, Kaposi’s sarcoma is less common in women than in men who have sex with men, owing to a difference in the prevalence of human herpesvirus 8.

HIV Cardiomyopathy

Advanced HIV infection is associated with dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.9 However, this diagnosis would not explain other features of this patient’s clinical presentation, such as the oral ulcers and headaches.

Bacterial Pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia occurs frequently in persons with HIV infection and may be due to one of several common or uncommon organisms, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, or Chlamydia pneumoniae. This patient had been exposed to farm animals, which suggests the possibility of infection with rhodococcus species (after horse exposure) or C. psittaci (after exposure to pet birds or poultry). Exposure to goats and sheep suggests the possibility of infection with Coxiella burnetii, but the patient’s normal levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase make this diagnosis unlikely. Legionella can be found in borehole water, which she had ingested, but it is more common in manmade aquatic reservoirs.10 Nocardia may cause pneumonia and spread to the central nervous system; nocardiosis is a consideration, given her new headaches. However, this patient had had cough and dyspnea for several months, which makes most types of bacterial pneumonia unlikely because they tend to have a more acute presentation and progress over a shorter period of time.

Mycobacterial Pneumonia

Patients with M. tuberculosis infection and a low CD4 cell count can present with opacities in the middle or lower lobes, lymphadenopathy, and a miliary pattern on chest radiography. Drug-resistant M. tuberculosis infection would be a possibility if the patient had had incomplete adherence to her antimycobacterial medications. However, 4 months before the current presentation, follow-up mycobacterial nucleic acid testing of the sputum had been negative, which makes this diagnosis unlikely. M. avium complex usually causes disseminated infection, rather than pulmonary disease, in persons with advanced HIV infection.

Fungal Pneumonia

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia is one of the most common opportunistic infections in persons with HIV infection. Patients with P. jirovecii pneumonia typically present with cough, dyspnea, fever, and hypoxemia, which is sometimes exertional. However, this diagnosis would not explain the patient’s oral ulcers or headaches.

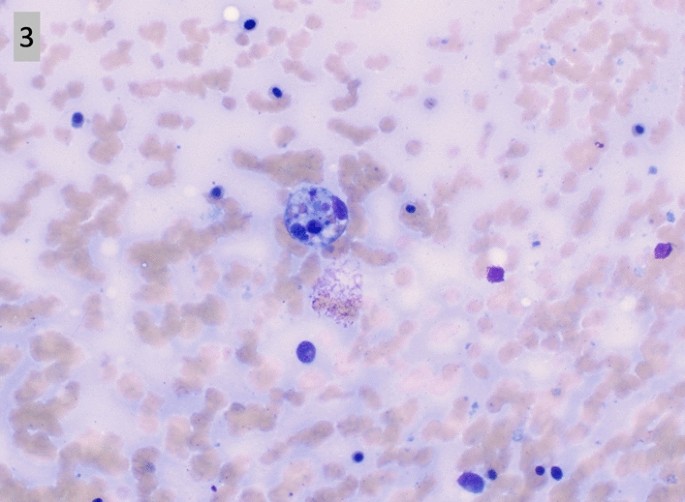

Other potential fungal causes of pneumonia in persons in southern Africa with advanced HIV infection are Emergomyces africanus (formerly emmonsia species), cryptococcus, aspergillus, blastomyces, and histoplasma. E. africanus is the most common dimorphic fungus implicated in human disease in southern Africa and can cause pulmonary or disseminated infection in persons with HIV infection.11 Cryptococcal infection may lead to pneumonia and often results in meningitis, which could explain the headaches in this patient. However, a serum lateral flow assay for cryptococcal antigen was negative, which rules out cryptococcal meningitis, although not cryptococcal pneumonia. Aspergillus can cause pulmonary infection; risk factors for pulmonary aspergillosis in this patient include the low CD4 cell count, leukopenia, and recent history of Covid-19 and tuberculosis.

Parasitic Pneumonia

Potential parasitic causes of pneumonia in persons with advanced HIV infection include toxoplasma, strongyloides, cryptosporidium, and microsporidium. However, other features of this patient’s presentation, including the oral ulcers and headaches, would not be easily explained by infection with these parasites.

Viral Pneumonia

Influenza tends to be more severe in immunocompromised patients, including those with advanced HIV infection.12 Viral pneumonia can also be caused by respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, human metapneumovirus, cytomegalovirus (although rarely in persons with HIV infection), or SARS-CoV-2.

REFINING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

After the patient’s initial respiratory symptoms, odynophagia and mouth ulcers developed. In a patient with advanced HIV infection, potential causes of these symptoms include infection with aspergillus, histoplasma, candida, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, or SARS-CoV-2. Noninfectious possibilities include lymphoma and aphthous ulcers. Only some of these causes would also explain her respiratory symptoms, with aspergillus, histoplasma, and SARS-CoV-2 infections leading the list.

Headaches also developed late in this patient’s clinical course. Possible causes include a focal brain lesion (including brain abscess), bacterial or fungal sinusitis, and meningitis. Bacterial causes are somewhat less likely to be the sole explanation, given her protracted disease course. It is notable that fungal infections, including aspergillosis, have been reported to cause sinus disease and focal brain lesions in persons with advanced HIV infection.

Finally, is there an explanation for the progression of shortness of breath, cough, headache, and mouth ulcers after the initiation of effective ART? The patient’s worsening condition may be attributed to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). She had risk factors for IRIS: low CD4 cell counts, a high HIV RNA level, and the recent initiation of effective ART. Multiple opportunistic infections and cancers can worsen after the initiation of ART. A potential case of IRIS in the context of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and Covid-19 has been reported.13

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

How can we best explain this patient’s initial respiratory symptoms, followed by the development of odynophagia, mouth ulcers, and headaches? Given her markedly immunocompromised state, I am concerned about the possibility of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported in immunocompromised hosts, including those with advanced HIV infection.14 In several cases, other opportunistic conditions or superinfections were also present.

The persistence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in persons with advanced HIV infection may lead to the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 viral mutations. In an instructive report, a severely immunocompromised woman with HIV infection was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA for more than 210 days; during that time, the spike gene of the virus developed multiple mutations associated with immune evasion.15 The patient eventually cleared SARS-CoV-2 RNA after her HIV RNA level was suppressed with the use of ART.16 This case and others highlight the importance of identifying persons with HIV infection, treating them with ART, and prioritizing Covid-19 vaccination and treatment in this population.

In addition, persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection would place this patient at risk for a superinfection that might explain the new onset of headaches. Superinfections that can occur after Covid-19 include fungal infections, such as aspergillosis or mucormycosis, which can lead to pneumonia or rhino-orbital cerebral disease. The mechanisms that confer a predisposition to fungal superinfection in patients with Covid-19 are unclear, but such superinfection may in part be related to epithelial injury by SARS-CoV-2 leading to enhanced fungal binding to airways or impaired antifungal immunity from lymphopenia.17 This patient had additional risk factors for aspergillosis, including advanced HIV infection, leukopenia, and potential lung disease related to her recent tuberculosis.17-19

Given this patient’s profound immunodeficiency, I suspect that she has persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may account for some aspects of her clinical presentation (fever, cough, dyspnea, and an abnormal lung examination). In the context of Covid-19 and a low CD4 cell count, pulmonary and cerebral aspergillus superinfection could be the cause of her respiratory symptoms and headaches. An additional evaluation, including SARS-CoV-2 testing as well as chest and head imaging, is warranted.

Dr. Rajesh T. Gandhi’s Diagnosis

Advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, persistent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, and pulmonary and cerebral aspergillus superinfection.

Diagnostic Testing

Figure 1. Results of RT-PCR Testing for SARS-CoV-2.

Results of RT-PCR Testing for SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Tulio de Oliveira: A reverse-transcriptase polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) test of a nasopharyngeal specimen was positive for SARS-CoV-2. Two gene targets were detected (the N gene and ORF1ab targets), but the S gene target was not detected. The mean cycle threshold value was 18.3. Details of two additional positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests were retrieved from laboratory records, the first from 11 months before presentation and the second from 3 months before presentation (Figure 1). No negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests were documented between the positive tests.Figure 2. Phylogenetic Tree of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Sequences.

Phylogenetic Tree of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Sequences.

Repeated positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests could reflect reinfections with different SARS-CoV-2 variants or persistent infection.20 Residual specimens from the current test and the test performed 3 months before presentation were retrieved for SARS-CoV-2 whole-genome sequencing; no stored specimen was available from the first test, performed 11 months before presentation. Results of phylogenetic analysis were consistent with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection; both genomes were clustered together on a long branch within the delta clade (Figure 2).Figure 3. Mutations in the Spike Gene.

Mutations in the Spike Gene.

The genomes showed substantial evolution from the delta variant (B.1.617.2), with amino acid changes particularly concentrated in the spike gene. As compared with the sequence for the delta variant, the sequence from the patient 3 months before presentation had 14 additional mutations in the spike gene (13 substitutions and one deletion) (Figure 3). The sequence from the patient at the time of the current presentation showed 5 additional amino acid substitutions in the spike gene, as well as a new deletion in the N-terminal domain (67–79del) that was probably responsible for the S gene target failure. Furthermore, there was evidence of continued evolution at a key neutralizing antibody escape residue, from F486L to F486V. Taken together, the genomic data strongly pointed toward persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection with intrahost evolution.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection and persistent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection.

Discussion of Management

Dr. Richard J. Lessells: Since late 2020, there have been multiple reports of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection with intrahost evolution, usually in immunocompromised hosts. In South Africa, we have documented persistent infections in persons with advanced HIV infection.16,21 Suspected persistent infections can be identified from longitudinal follow-up of individual patients in clinical care or research studies, from active surveillance for suspected reinfections or persistent infections, or from targeted investigation of unusual sequences obtained during routine genomic surveillance.

There are no specific evidence-based management guidelines for persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection.22 Case reports of persistent infection have described treatment with antiviral agents, monoclonal antibodies, and convalescent plasma, often in combination, but the efficacy of any single or combination therapy for persistent infection has not yet been established.23,24 At the time of the patient’s current presentation, antiviral agents (remdesivir, molnupiravir, and nirmatrelvir–ritonavir) and monoclonal antibodies were either not yet approved or not available for use in the public health sector in South Africa. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies are no longer active against circulating subvariants of the omicron variant (B.1.1.529).

Effective treatment of the underlying disease is an essential component of the management of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients. Limited evidence from case reports of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with advanced HIV infection suggests that effective clearance of SARS-CoV-2 can occur after the commencement of effective ART and HIV suppression.16,21 Given the treatment history in this patient, the ART regimen was changed to a once-daily fixed-dose combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, and dolutegravir just before the current presentation.

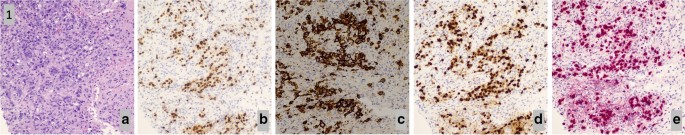

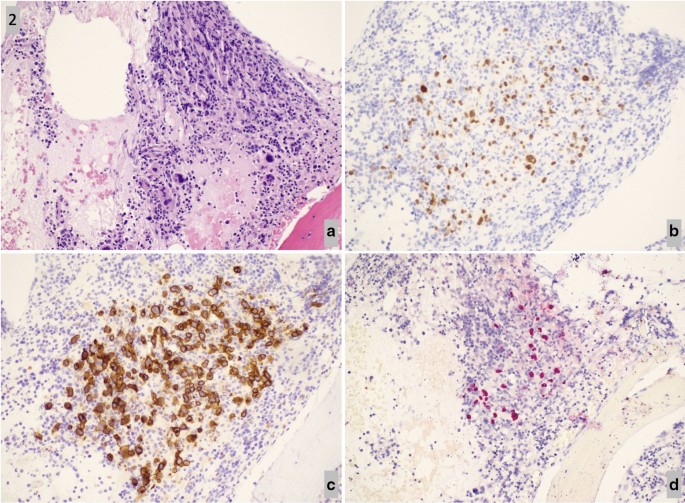

Follow-up

Dr. Nithendra Manickchund (Internal Medicine): Because no antiviral therapies for SARS-CoV-2 infection were available in South Africa at the time of the patient’s current presentation, the goal was to suppress HIV replication and reconstitute her immune system to resolve the Covid-19. Five weeks after the ART regimen was changed to a dolutegravir-based regimen, the patient began to have severe headaches on the right side, ptosis of the right eye, and an inability to move her right eye laterally. She presented to the clinic with these acute neurologic changes and was transferred to the hospital out of concern for IRIS. Computed tomography (CT) of the head, performed after the administration of intravenous contrast material, revealed a mass in the cavernous sinus with occlusion of the right internal carotid artery. Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated from two sputum specimens. On review of a second CT scan of the head, the mass was thought to be suggestive of aspergillosis, and treatment with intravenous amphotericin B was initiated.

RT-PCR testing of nasopharyngeal specimens for SARS-CoV-2 remained positive for the first 2 weeks of the hospitalization, but the infection had resolved by the third week. The patient neared HIV suppression at that time, with an HIV RNA level of 118 copies per milliliter of plasma, and had a modest improvement in the CD4 cell count. While awaiting biopsy for the intracranial mass, the patient died suddenly in the hospital. A postmortem examination was not performed.

Final Diagnosis

Advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, persistent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, and rhinocerebral aspergillus superinfection.