For this issue of Inside Precision Medicine focused on gender medicine, I was asked to write a piece about overlooked diseases that affect women. This list is long and includes, among others, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and several autoimmune disorders like lupus and multiple sclerosis. However, for reasons that will become clear, I chose to focus on Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS).

EDS is not one disease but a heterogenous group of 13 heritable connective tissue disorders, characterized by joint hypermobility, skin hyper extensibility, and tissue fragility, as classified by the International Consortium on Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and Related Disorders in 2017. To date, 19 causal genes, mainly involved in collagen and extracellular matrix synthesis and maintenance, have been associated with 12 of these 13 EDS subtypes. In 2018, a 14th subtype, with a novel variation in the AEBP1 gene, was discovered but it has not yet been named and classified.

The only subtype that does not have an associated pathogenic variant is hypermobile (h)EDS. It is also the most common, with an estimated prevalence of around 1 in 3,100 people, as reported by The Ehlers-Danlos Society.

In contrast, 11 of the 14 subtypes (periodontal EDS, kyphoscoliotic EDS, spondylodysplastic EDS, brittle cornea syndrome, arthrochalasia EDS, musculocontractural EDS, classical-like EDS, dermatosparaxis EDS, myopathic EDS, cardiac-valvular EDS, and the AEBP1 subtype) are extremely rare, affecting fewer than one in a million people worldwide. The remaining two, classical EDS and vascular (v)EDS, have a reported prevalence of 1 in 20,000–40,000 and 1 in 100,000–200,000, respectively.

Women are disproportionately represented among people with EDS. They account for more than 70% of cases published in the literature but to date, there is no obvious genetic reason for the gender bias. In the context of this rare disease that primarily affects women, it is not surprising that patients must overcome some huge challenges before receiving a diagnosis.

As EDS is a connective tissue disorder, the affected tissues and organs are spread throughout the body. This can make diagnosis and management difficult. Patients frequently have multiple symptoms such as widespread pain, severe fatigue, easy bruising, fragile skin, joint dislocations, gastrointestinal symptoms like difficulty swallowing, nausea, vomiting, and food intolerance, and autonomic symptoms such as heart palpitations, excessive sweating, and fainting. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach needed to ensure optimal care.

CEO, The Ehlers-Danlos Society

Lara Bloom, CEO of The Ehlers-Danlos Society, says that the average wait for diagnosis is still 10 to 12 years, and even longer in developing countries where there is less awareness of EDS. During this time, many patients leave their studies or successful careers because their bodies do not function well enough to allow them to continue. This can impact their financial situations and personal relationships, particularly as without a diagnosis patients’ symptoms may not be taken seriously.

Although there are currently no specific treatments for EDS, there are ways to manage its symptoms. Bloom says “it is a huge disservice to patients when they’re not receiving that management and care, as even the simple validation of being believed goes such a long way and that is still not happening.”

Misdiagnosis plays a large part in a delayed EDS diagnosis. “We still have lots of people with symptoms being blamed on anxiety and depression or hormones and it’s simply not good enough,” says Bloom. “In addition, we are now seeing more people with hypermobile EDS, which historically did not shorten your life expectancy, dying from highly avoidable causes such as suicide or complications with malnutrition from gastrointestinal symptoms that were missed or put down to psychological issues.”

The Ehlers-Danlos Society, people with an EDS, and other patient advocacy groups have adopted the zebra as their symbol. The Ehlers-Danlos Society explains that medical students have been taught for decades that, “when you hear the sound of hooves, think horses not zebras.” In other words, look for the common diagnosis and not the surprising one. Yet sometimes when you hear hooves, it really is a zebra and people with an EDS or hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) are those unexpected cases.

Furthermore, no two zebras have identical stripes, just as no two people with an EDS or HSD are the same. They have different symptoms, different types, and different experiences. The Ehlers-Danlos Society says “we are all working towards a time when a medical professional immediately recognizes someone with an Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or HSD, reducing the time to diagnosis and improving pathways to care.”

A recent study by Colin Halverson, PhD, from the Center for Bioethics at Indiana University School of Medicine, and colleagues showed that people with hEDS have an average of ten co-diagnoses, most common of which are anxiety, depression, postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and irritable bowel syndrome. However, the study, which included 505 individuals with hEDS (91% women, 97% White) showed that 42% of these diagnoses were not endorsed as accurate by the patients.

The most rejected co-diagnoses were functional neurologic disorders (rejected by 95%), multiple sclerosis (76%), fibromyalgia (67%), bipolar disorder (62%), and ulcerative colitis (58%) and the most endorsed were POTS (91%), cervical instability (90%), mast cell activation syndrome (86%), temporo-mandibular joint disorder (85%), and small fiber neuropathy (83%).

The study participants saw an average of 15.6 clinicians (24% reported that they saw 20 or more) prior to diagnosis, with an average time to diagnosis of 10.4 years. The majority (57%) received their official hEDS diagnosis from a genetics specialist, followed by a rheumatologist (20%) and their primary care physician (5%). Following diagnosis, the average number of clinicians each patient saw dropped to 7.5.

“Because genetic markers have yet to be established to aid in diagnosis of hEDS, building an understanding of the specific phenotypes and of the variations within the presentation of hEDS is a crucial step in improving patient outcomes,” Halverson et al. wrote. They said that the study demonstrated the complexity of hEDS and stressed “the need for an interdisciplinary team approach for the appropriate management and care.”

Compounding the difficulties faced by patients is a lack of targeted funding, which Bloom says is the biggest challenge of all. She points out that in the U.K. there are very few National Health Service (NHS)-funded EDS clinics, while in the U.S. there is limited funding from the National Institutes for Health. “Other than us [The Ehlers-Danlos Society], there’s very few places where you can get funding to study these conditions.” Over the past five years, The Ehlers-Danlos Society has given out $6–8 million in funding, which will allow researchers to “start to etch away at the things that are needed,” says Bloom.

associate professor

University of Illinois and the

Carle Illinois College of Medicine

Two of the largest projects funded to date are the EDS and HSD Global Registry and the Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Genetic Evaluation (HEDGE) study. These two projects are important because the lack of reliable genetic causes for hEDS means that diagnosis currently rests on clinical criteria, which can be difficult to distinguish from other HSDs.

“This, in part, likely reflects genetic heterogeneity,” says Christina Laukaitis, MD, an associate professor at the University of Illinois and the Carle Illinois College of Medicine, who will lead analysis of the whole-genome sequencing data obtained for HEDGE with Joel Hirschhorn, PhD, MD, Concordia Professor of Pediatrics and Professor of Genetics at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

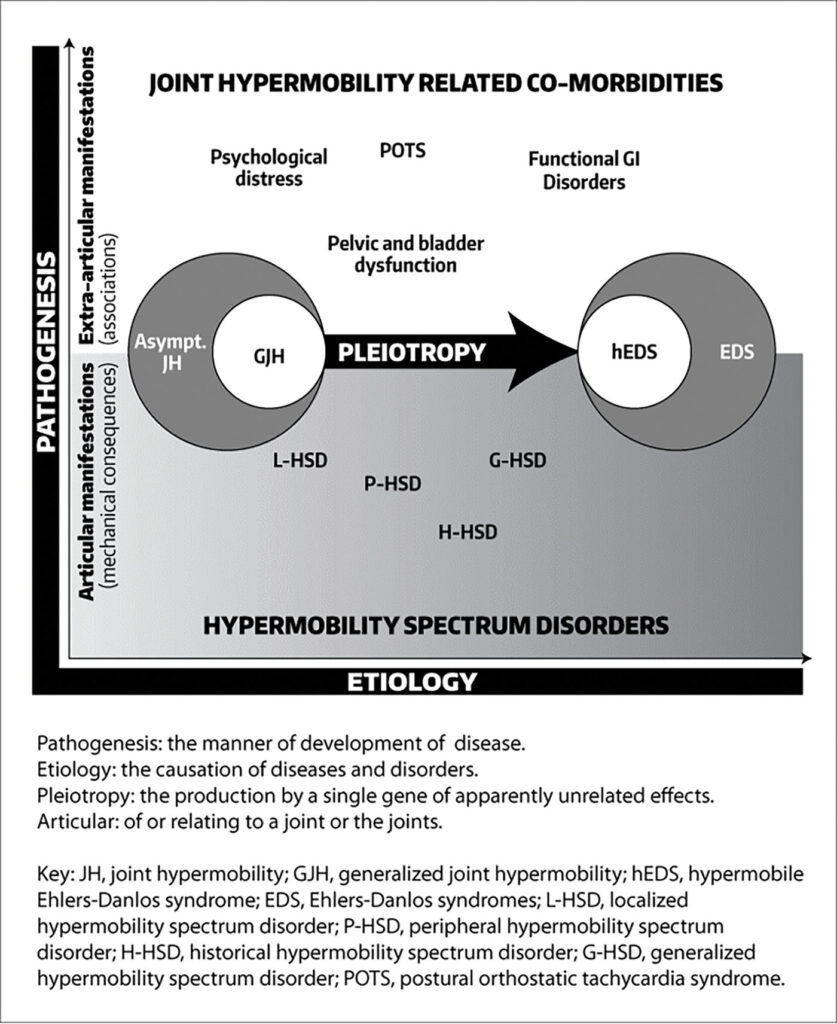

“In addition, there is a clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic joint hypermobility, through ‘non-syndromic’ hypermobility with secondary manifestations, to hEDS,” notes Laukaitis.

The concept of a spectrum of pathogenetically related manifestations of joint hypermobility (JH) was introduced by Marco Castori, MD, PhD, and colleagues in 2017. They noted that the 2017 classification criteria for hEDS led to the unification of two disorders—EDS-hypermobility type and JH syndrome—that were originally recognized by different sets of diagnostic criteria. However, this leaves many individuals with symptomatic JH and/or features of hEDS who do not meet the stricter hEDS criteria without an “identity.”

Castori et al. proposed that individuals with JH be classified into one of three groups: those with asymptomatic JH, those with a well-defined syndrome with JH, including hEDS, and those with symptomatic JH that does not meet the criteria for a syndrome. The term HSDs was proposed for people that meet the last criteria.

Although some experts believe that hEDS and HSD are essentially the same condition along a spectrum—with a combined prevalence of 1 in 600 to 900—others believe they are distinct conditions with different genetic causes.

The HEDGE study was launched in 2018 as a worldwide collaborative effort devoted to finding the genetic markers underlying hEDS. Since then, 1,021 people with hEDS from 86 countries have undergone whole genome sequencing, making it the largest study of hEDS genetics to date. The study entered its analysis phase in the spring of 2023, with the final results expected in a year or so.

Laukaitis says the HEDGE researchers are “expecting to find a number of gene candidates” for hEDS. They are also looking at some that were previously proposed along with those already associated with other EDS types. The team will analyze these known genes to not only ensure that people with other types of EDS are not mistakenly categorized in the hEDS cohort, but also find other variations within those genes that could affect the encoded protein differently from the classical mutation.

However, Laukaitis stresses that hEDS is likely not caused by just a single gene. “You know, we’ll be lucky if we have three or four major genes and less than a dozen minor ones. I really expect this to be complicated,” she remarks. “Hopefully, by the time we’re done with HEDGE in 12 months, more or less, we’ll at least have a sense of what the genetic milieu will be, and a number of genes that are ready to go through final validation and start being used clinically.”

Even if candidate genes are identified, Bloom says there will always “be a group within [the EDS] umbrella that do not have a genetic marker that we can find. We still need to make sure that they have the management and treatment that they need and deserve.” She also thinks that hEDS and HSD could “be the most mis- and underdiagnosed condition of our time.”

To aid the understanding of symptoms of these two conditions and other types of EDS, The Ehlers-Danlos Society launched the EDS and HSD Global Registry in 2018. The registry has collected standardized health information from more than 13,000 patients from 16 countries. It will allow researchers to compare and analyze patient data on a much larger scale than has been possible with individual research studies.

Other research groups that have recently received funding from The Ehlers-Danlos Society are the Norris Lab at the Medical University of South Carolina, who will be carrying out a separate study to identify a gene candidate for hEDS, and a group at John Hopkins University led by Harry Dietz, MD, who is trying to understand the mechanism driving vascular fragility and rupture in vEDS with the aim of developing new treatment strategies. Work is also underway at the University of Ghent in Belgium to elucidate the mechanisms causing hEDS using a multiomics approach. In addition, Clair Francomano, MD, is leading a study at the Indiana University School of Medicine to find out whether hormones impact symptom presentation and severity in hEDS.

The Ehlers-Danlos Society also supports research into the rarer subtypes of EDS, like a study to understand the significance of the mutations that cause kyphoscoliotic EDS and studies that look at the impact of EDS on patients’ lives.

In the commercial sector, work on developing treatments for any of the EDS subtypes is limited. Acer Therapeutics is carrying out a Phase III trial of the beta-blocker celiprolol in people with COL3A1-positive vEDS. It is already approved for use in the U.K., but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires further evidence that the drug reduces the occurrence of vEDS-related clinical events, such as fatal and non-fatal cardiac or arterial events, uterine rupture, intestinal rupture, and/or unexplained sudden death, relative to placebo before granting approval.

A Phase III clinical trial of another potential treatment for vEDS, enzastaurin, was announced by Aytu BioPharma in July 2022. Enzastaurin is a first-in-class small molecule that showed preclinical efficacy in inhibiting a signaling pathway that drives vEDS. Unfortunately, Aytu BioPharma announced in October 2022 that they were suspending all clinical development programs to focus on revenue growth. No patients were treated with enzastaurin and to date, there is no indication as to when the trial might recommence.

Alongside clinical trials and laboratory-based research, The Ehlers-Danlos Society funds the EDS ECHO program, which is based on the “all teach, and all learn” philosophy of Project ECHO®. “Project ECHO is phenomenal,” says Bloom. She explains that it was founded by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico to ensure more people had access to best-practice care for hepatitis C. He noticed that patients who did not have access to local care became sicker while waiting to travel to his clinic, so he set up a tele-mentoring program “to move knowledge, not patients,” Bloom notes.

EDS ECHO is a series of programs and courses for healthcare professionals across all disciplines who want to improve their ability to care for people with EDS, HSD, and associated symptoms and conditions. The tele-mentoring platform has already reached nearly 2,000 people across a wide area of the globe, with specific programs for clinicians, fundamentals of the Integral Movement Method, advocacy, allied health professionals, pediatrics, genetics and genomics, vEDS, and nutrition. It allows participants “to learn from experts and is a wonderful way to educate and support the healthcare professionals,” says Bloom.

Bloom believes that now is a transformative time for EDS. “We’re on the horizon of lots of change and discovery,” she says, adding that publications coming in the next few years, including the HEDGE study and data from EDS ECHO, will provide strong foundations for future work and show that “this is not a condition to be disputed any longer.”

Bloom continues, “We can finally move forward with education and what I always say critically is re-education, because there are so many people out there who think they know what EDS and HSD are and that they are benign conditions that just make you a bit bendy, but we know it’s so much more than that.

“It’s impacting people’s lives and you can have a good quality of life with EDS and HSD if you get diagnosed when your symptoms begin, and you have access to long-term management and care because these are chronic conditions. Six weeks of physiotherapy is not going to cut it, we need to truly understand the full picture and the full multisystemic nature and then manage it appropriately.”

Hypermobile EDS: two journeys toward diagnosis

Faye’s story

I first met Faye at an antenatal class 11 years ago. There were eight pregnant women and their partners in the room—she was the only one on crutches who had to leave to vomit after the coffee break. As we all got to know each other, we found out that she was experiencing severe pelvic girdle pain (PGP, which affects around 20% of pregnant women to varying degrees) and hyperemesis gravidarum (occurring in 1–3% of pregnancies) that had landed her in the hospital on several occasions. Although a thoroughly miserable experience, Faye put it down to one of those things. She had always had some quirky health issues and was happy to be focusing on her healthy baby boy.

Fast forward four years: Faye was juggling her full-time job in educational leadership with running around after a little boy when she found out she was pregnant with her second child. At five weeks, the hyperemesis gravidarum started and again, despite being on many medications, resulted in multiple hospitalizations. By the end of the pregnancy, Faye was in a wheelchair due to PGP and agreed to a cesarean section because she was so ill. The operation went well but afterward, Faye physically could not move because of pain in her hips. She was discharged a week later, unable to walk, and spent the next three months in a bed that had been set up in a downstairs room for her. She was still vomiting regularly and it was a year before she could walk properly again, but nobody knew why. It was around this time that she also started experiencing dizziness and blacking out.

It took another two years, multiple appointments, and a change of general practitioner (GP) due to a house move for Faye to get some understanding what was going on. She went to her new GP with fatigue and pain and was referred to a rheumatologist, who she said was the first person to ask her to start from the beginning with a list of all of her symptoms. The rheumatologist asked Faye to touch her toes and perform other exercises, which she now knows make up the Beighton score—a measure of hypermobility—and then diagnosed Faye with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

“I came out of the appointment and cried, because somebody had actually diagnosed me with something that everybody else had been telling me there’s nothing wrong with me and it’s all in my head,” says Faye.

The rheumatologist then discharged her with referrals to multiple specialists: a cardiologist who diagnosed POTS, an orthopedic surgeon to consider foot surgery, a physiotherapist, and a rheumatherapist. Then came diagnoses of postpartum hypothyroidism and osteoarthritis. Faye has also seen or continues to see a dietician, neurologist, an oral medicine specialist, and attends an allergy clinic.

Despite receiving a diagnosis, Faye faces challenges every day. “The rheumatologist [who diagnosed me] changed my life in one way, but killed it off in another way,” she says. She is now categorized as disabled and had to take an extended break from her career, which had financial implications. It impacted her marriage as her husband must now “pick up the slack” when she is too exhausted or in too much pain to do things, and it has given her a very different perspective of the medical profession.

“There is so much gaslighting, people saying I’m making it up or having mental health issues,” she says. One incident was particularly upsetting. Faye had an appointment with an oral medicine specialist to investigate transient blood blisters on her tongue and the inside of her cheeks. On the day of the appointment, she was having a “good day” with few symptoms but explained to the consultant what usually happens, stressing that the blisters were not a result of biting her tongue. After further conversation, he told her he thought she was definitely biting her tongue.

Faye did not have the energy to complain and instead contacted Ehlers-Danlos Support U.K., who put her in touch with a private allergy specialist who diagnosed mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). She also has idiopathic anaphylaxis, idiopathic edema, and idiopathic urticaria. The treatment she was given by the private specialist for MCAS completely cleared the symptoms, but it was not simple because the “NHS either don’t recognize the condition at this point or won’t pay for the drugs,” resulting in excessive private prescription charges. There is also no one to oversee all her prescriptions, putting her at risk for dangerous drug-drug interactions.

Faye describes the care she has received as a “system of chaos” and says that one thing that could improve her quality of life and treatment is some sort of flag on her medical record that immediately shows all treating physicians that she has hEDS and is under the care of multiple specialists. This does not exist and instead, she carries a large folder of medical letters to every appointment with information on each of her diagnoses and treatments. In addition, there is no specific individual coordinating her care. This is meant to be the responsibility of the GP, but the current difficulties in obtaining GP appointments means that the coordination simply does not happen.

Another frustration is the management of all the medical appointments that she attends. “Sometimes I have an appointment a week, sometimes more, and trying do any sort of work with that is nigh on impossible,” she says. “On top that, you have situations where you receive a letter that says you didn’t attend an appointment, then the next day receive the letter for that appointment. This is followed by another letter saying you’ve been discharged from the service—that you’ve been waiting to see for six months—because you failed to attend the appointment and that happens so much.”

Aside from more organized care, Faye would like to see people with EDS gain access to more proactive support like neurotherapy gyms where the staff “are not scared if you have to sit on the floor every five minutes,” to help with rehabilitation and more education for not only medical professionals but also across schools, particularly among PE teachers.

She appreciates the work that Lara Bloom and The Ehlers-Danlos Society are doing to improve the lives of people affected by EDS but wants more people to be shouting about it. “Just because it’s rare doesn’t mean it’s not important,” she says.

Claire’s story

I met Claire at a baby group around four months after I met Faye. As I got to know her, I was intrigued by the similar experiences the two women had had during pregnancy. Claire also experienced PGP and was hospitalized multiple times with hyperemesis gravidarum, but I put it down to coincidence. I did not know that throughout her life she had experienced numerous symptoms that were characteristic of hEDS.

At primary school she struggled with her handwriting, experiencing joint pain when holding a pen or pencil. In her early teens she was diagnosed with Osgood-Schlatter Disease, a condition that causes pain and swelling below the knee joints, and had to give up competitive sports because of recurrent injuries. In her later teens she experienced fatigue and bowel problems that were put down to a psychological issue and possible glandular fever. She had to repeat exams and delay graduating from her degree in physiotherapy. She was eventually signed off sick from work for 18 months due to what was thought to be post-viral chronic fatigue syndrome.

“I’d spent years going to the GP and it was always put down to stress; GCSE stress, A-level stress, university stress, new job stress, a stressful long commute to work, then I changed jobs to be closer to home. I didn’t have the commute anymore but still had the symptoms,” she says.

“And then I had a car accident in February of 2016. My life got blown apart, I went from being a busy mum to not being able to do anything. In 2018 I was medically retired in my mid-30s from a job I had wanted to do since I was 14 and needed to use a wheelchair.”

The car accident was not the kind most people would expect to have such an impact. Claire was stationary at traffic lights when a car shunted her from behind into the car in front. She thought she was fine, but that evening began to experience pain and stiffness in her neck that she presumed was whiplash. However, the collision set off a chain of events that ultimately led to the diagnoses of cervical instability (excessive movement in the top two vertebrae of her spine), cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (the brainstem sits on the top of the spinal cord and not in the skull), POTs, and idiopathic angioedema.

Despite this, Claire does not have an official EDS diagnosis. A rheumatologist has said she has benign JH, but this is an outdated term (Castori et al. said in their 2017 framework that its use should be discouraged for the classification of JH and related conditions) and does not account for her other symptoms. A neurocardiologist has spoken to her about EDS and was the only person to go over her full medical history, right back to primary school. But Claire says he was unable to give her a formal diagnosis because it was not his area of specialty and the diagnosis had to come from the rheumatologist.

Claire is not planning to chase that diagnosis even though it would validate her experiences, because people would then ask why she “needs” it and question the underlying mental health reasons. Indeed, at one point a neurologist referred her to a neuropsychiatrist because he believed she had functional neurological disorder. Having worked in healthcare, Claire says she knows that this can be a damaging diagnosis as many clinicians believe that one cannot treat patients with functional neurological disorder because it is “all in their head.” Yet, she could not refuse the referral because that would also go in her notes. When she went to the neuropsychiatrist, the doctor said that she did not need to be there.

“That’s the problem with EDS, you have multiple systems involved and no one pieces it all together, so you end up presenting like a hypochondriac,” Claire says.

She has faced similar problems to those faced by Faye throughout her diagnostic journey and highlights the financial impact a condition like EDS can have on a patient. She lost her income, had to pay to see specialists privately, and even funded her own electric wheelchair because NHS Wheelchair Services could only provide limited support. The NHS said that because her house was too small for her to use the wheelchair indoors, they would only fund an attendant-propelled wheelchair. This meant that she was not allowed to push herself because of her cardiac valve problems and would always be reliant on someone else to push her. All she wanted was to be able to get out and about independently with her daughter. Eventually, her sisters set up a GoFundMe page to raise the £6500 that was needed. They reached the target within 48 hours, which was “humbling and amazing and gave me a life that I couldn’t have had without it.” But Claire had initially rejected the idea. Till then she had kept her medical history fairly private and putting herself “out there” made her feel very vulnerable.

Like Faye, Claire believes that having someone to oversee her multidisciplinary care, be that a case manager, a nurse, or physiotherapist, would make a massive difference. Easier access to acute medication like strong painkillers and muscle relaxants would also help. She now has an understanding GP who is a “rare gem” because she has a “two-way conversation where we deal with it together.” The GP has prescribed Claire a small amount of diazepam to have ready at home if she experiences a torticollis (wryneck), which Claire says makes sense as it means avoiding a trip to hospital. Faye has tried to have something similar arranged for when she experiences joint dislocations, but has not yet been successful.

Claire says she has come to peace with the fact that she will not get back to work as a physiotherapist. She has a part time job that allows her to work from home, but she still feels a bit lost as it is difficult to plan for anything when symptoms fluctuate so much. She manages it with modified exercise, splints for joints when needed due to subluxations, treatment from her husband who is also a physiotherapist, rest, and activity management that has become part of her daily life. She continues to use her wheelchair and other mobility aids as required to manage fatigue and pain and as preventive measures. She says there still needs to be more support for people with EDS. “The medical professionals need to be supporting you and right now the majority are not.”