Researchers at the Mayo Clinic investigating factors related to recovery from dilated cardiomyopathy have identified a variant in a specific gene that plays a role in people who recover from the condition and those who don’t. Results of the genome-wide association study (GWAS), published in Circulation Research, is expected to spur future research to target the gene for future dilated cardiomyopathy treatments.

“We found genetic variation in the CDCP1 gene, a gene that no one has heard of in cardiology, and its link to improvement in heart function in these patients,” says lead author Naveen Pereira, MD, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist.

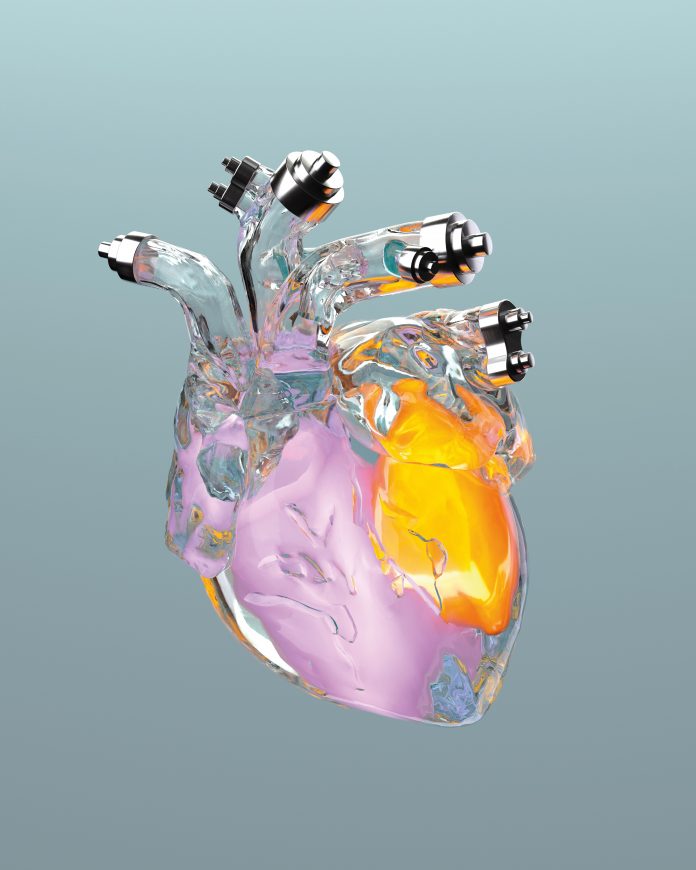

Cardiomyopathy is characterized by its effect on the heart’s left ventricle, making it more difficult to pump blood throughout the rest of the body.

According to the investigators, CDCP1 genetic variation leads to differences in the protein’s structure which may influence a person’s susceptibility to disease or response to specific drugs. Once the gene was associated with improving function in the left ventricle, the team examined why this occurs. A key finding was that the CDCP1 gene is often variably expressed in fibroblasts of people with dilated cardiomyopathy, and fibrosis—an excess of fibrous connective tissue in the heart—plays a central role in prognosis of patients with the condition. Further, Pereira noted that genetic variation in or near CDCP1 has a significant association with heart failure death.

Strengthening the case for CDCP1 as a drug target, the Mayo Clinic researchers observed that decreasing the expression of the gene in cardiac connective tissue decreased fibroblast proliferation in the heart. It also downregulated the IL1RL1 gene, which encodes a prominent heart failure biomarker aST2, which when found in high levels is associated with fibrosis and death. This suggests the importance of developing a better understanding of the relationship between CDCP1 and aST2, as researchers search for ways to treat heart failure.

This finding now comes as heart failure rates are expected to rise significantly over the rest of the decade. The American Heart Association forecasts that heart failure will affect eight million people in the U.S. by 2030, a 46% increase over current rates. Of those cases, between 30% and 40% are caused by dilated cardiomyopathy.

Building in this research, the Mayo Clinic team is continuing studies in animal models to better understand the role CDCP1 plays in heart failure, and they are developing molecules to assess their potential as treatments for dilated cardiomyopathy.

“By continuing with this research that started with a human population that we took to the molecular and now animal laboratory, we hope to find new avenues for treatments to take back to the human population we studied, to improve patients’ survival and quality of life ultimately,” says Pereira.